A Comprehensive Guide to Crafting Chord Progressions in B Minor

Master chord progressions in B Minor by analyzing famous songs. Explore diatonic and chromatic harmonies, secondary dominants, chromatic mediants to unlock your unique sound.

Introduction

This article explores writing compelling chord progressions in B minor. We'll start by analyzing effective progressions from popular songs, uncovering the theoretical principles behind their appeal.

Next, we'll examine ways to enrich your own progressions, delving into techniques like secondary dominants, parallel chords, and key modulations, explaining the music theory behind them and their contribution to sophisticated musical textures.

Finally, we'll discuss the crucial role of cadences, demonstrating how their strategic placement builds and releases musical tension.

Building Blocks of B Minor

Crafting compelling B minor chord progressions requires understanding the key's foundational structure and the role of each chord. We'll touch on the basics here, but for a deeper dive, see "Chords in B Minor: A Comprehensive Guide".

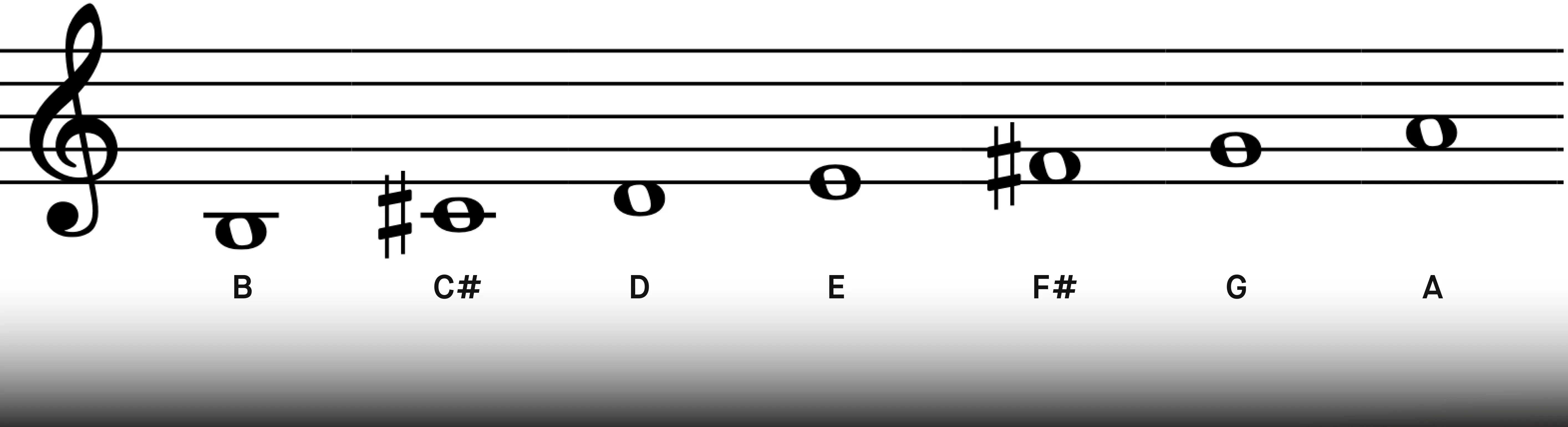

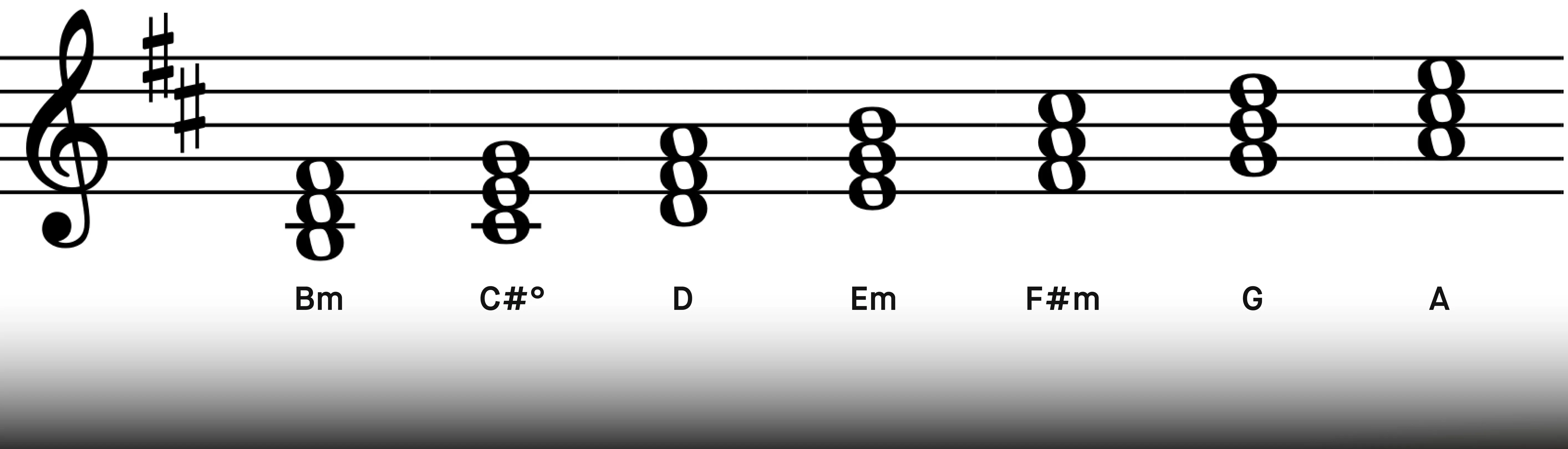

The diatonic chords in B minor are derived from the seven notes of the B minor scale.

To write intriguing chord progressions in B minor, it’s important to understand the foundation of the key signature and the function of each individual chord.

From these notes, we can construct the following diatonic chords in B minor: B minor, C# diminished, D major, E minor, F# minor, G major, and A major.

Common Chord Progressions in B Minor

The following B minor chord progressions offer a glimpse into the rich harmonic possibilities of this key. You'll find examples incorporating techniques like secondary dominants, parallel chords (both are explored in detail later), tonic substitutions, the major dominant 7th chord to create a leading tone, and more.

Studying these progressions will showcase the harmonic function of each chord and how these songs build anticipation and interest.

Let's explore common chord progressions in B minor.

i (Bm) - v (F#m) - iv (em) - III (D) - VI (G)

The iconic outro of Guns N' Roses' "November Rain" modulates from B major to B minor, employing a chord progression that perfectly balances major and minor elements, contributing to its anthemic quality.

The inclusion of the minor dominant (F#m) is a big part of the progression's momentum and development. The dominant F#7 builds tension that needs to be resolved. However, in this context, the tension provided by the minor dominant chord perfectly adds anticipation without the need for a full resolution. This delayed gratification enhances the emotional impact of the outro.

i (Bm) - V7 (F#7) - VII (Asus2) - IV9 (E9) - VI (G) - III (D) - iv7 (Em7) - V7 (F#7)

This extended chord progression possesses a restless, ambiguous quality. The use of seventh chords and extensions creates a constant state of anticipation and instability, which is engaging.

Although the song is in B minor, the progression avoids returning to the tonic until it repeats, contributing to a feeling of harmonic instability and a lack of clear tonal direction.

This same progression can also be heard in the Eagles' "Hotel California".

i (Bm) - III (Dmaj7) - VI7 (Gmaj7) - V (F#) - III (Dmaj7) VI (Gmaj7)

Deadmau5's "I Remember" features this same progression but with a particularly interesting twist: the dominant chord functions as a tonic substitute. It appears in places where we'd typically expect the tonic chord, creating a surprising harmonic effect. This substitution of the major dominant for the tonic instantly shifts the song's mood, adding an unexpected layer of tension and color.

i (Bm) - VI (G) - III (D)

This simple yet effective progression, famously used in Avicii's "Wake Me Up", relies on the tonic and two tonic substitutes, resulting in significant shared notes between the three chords.

This shared tonality creates a strong sense of connection between each chord. The B minor tonic feels particularly somber in contrast to the two major chords that follow. Within the country-infused context of"Wake Me Up", this contrast adds an interesting layer to the storytelling, evoking a sense of both hope and longing.

i (Bm) - III (D) - II (C#) - II (C) i (Bm)

This chord progression begins on the tonic, leaps to the mediant, and then chromatically descends back to the tonic. This descent is achieved through the use of chromatic chords. From the mediant, an altered C# chord is introduced, followed by a C major chord from the Phrygian mode – characterized by a lowered second degree.

This chromatic descending line creates unexpected and intriguing harmonic movement. Britney Spears' "Gasoline" provides a great example of this technique in action.

i (Bm7) - VI (Gmaj7) - i (Bm7/F#) - iv (Em add9) - VI (Gmaj7) - i (Bm7/F#) - iv (Em add9) - i (Bm)

Radiohead's "There There" uses this chord progression to achieve two distinct effects. First, the prolonged opening on the Bm7 chord firmly establishes the song's key. Second, the subsequent movement through extended and inverted chords creates a sense of harmonic instability.

This technique of balancing instability with a strong tonal anchor is particularly effective in conveying feelings of unease or ambiguity, making it a powerful tool for expressing lyrical themes of insecurity. The harmonic tension and release beautifully complement the emotional weight of the song.

The B minor chord in this context evokes a sense of comfort and stability, a musical"there there"that provides a feeling of safety.

VI (G)- i (Bm) - VII (A) - III D/F#)

A powerful way to inject immediate energy and dynamism into music is to begin a chord progression with the subdominant. Rihanna's "Diamonds" provides a perfect example.

Starting with the subdominant leverages its inherent tension and anticipation, as it naturally gravitates towards the tonic or dominant. This immediately engages the listener, as the unresolved nature of the subdominant creates a sense of expectation and forward momentum. This technique is particularly effective in genres like pop, rock, and electronic dance music, where a strong sense of drive and energy is often desired.

i (Bm) - III (D) - VI (G) - iv (Em)

Kelly Clarkson's "Dark Side" uses this chord progression to great effect. The opening three chords – tonic, mediant, and submediant – establish a strong tonal center due to their shared tones.

The harmonic stability these chords provide highlights the minor iv chord that completes this four-chord progression. Interestingly, despite the song being in a minor key and beginning on B minor, the overall feel leans toward major. This makes the subsequent E minor chord feel even more poignant and impactful.

VI (G) - i (Bm) - VII (A) - iv (Em)

M83's "Midnight" provides another example of a song that begins its progression on the subdominant chord for an immediate surge of energy. The song also features an intriguing interplay between major and minor tonalities, creating a sense of harmonic ambiguity.

The use of the VII and iv chords together is particularly noteworthy. M83 effectively uses this pairing in both the slower verses and the high-energy chorus. The ambiguous nature of these chords complements the song's instrumentation and overall mood.

i (Bm) - VI (G) - iv (Em) - V (F#) - iv (Em)

This harmonically robust and complete chord progression is featured in Queen's "The Show Must Go On". What makes their use of it particularly ingenious is that the iconic melody in the intro is directly derived from these chords.

By creatively alternating between triads, sus chords, and inversions, Queen wrote one of their most memorable and recognizable melodies.

This exploration of different voicing's and harmonic textures within the underlying progression is what gives the melody its distinctive character. The sus chords add a touch of yearning and anticipation, while the inversions create smooth voice leading and a sense of movement.

i (Bm) - i (Bm/A) - VI (Gmaj7) - bI (Bb) bII (C)

This chord progression is intriguing due to the ambiguity of its second chord. It can be interpreted as a B minor chord with A in the bass, or as an A13 chord omitting the third and fifth. Regardless of the interpretation, this chord adds depth, interest, and intrigue to the progression's character.

The inclusion of the ♭I and ♭II chords further enriches the harmony, venturing beyond the diatonic realm of B minor and adding a layer of complexity. Notably, the first three chords create a descending bassline, culminating on G. From there, the progression moves via a chromatic mediant (discussed later) to Bb and then C major borrowed from the phrygin mode.

Bruno Mars' "Gorilla" features this compelling harmonic progression.

v (F#m) - i (Bm) - IV (E) - iv (Em) - VI (G) - VII (A)

Bruno Mars' "Gorilla" also uses this intriguing chord progression in its pre-chorus, notably featuring a shift from E major to E minor. This harmonic sleight of hand can instantly alter the mood of a progression and the entire song.

The direct juxtaposition of major and minor qualities makes the minor version feel particularly somber and impactful.

Spice Up Your Chord Progressions: Creative Uses of B Minor Chords

Chord Inversions

Chord inversions provide a powerful tool for creating smoother, more natural-sounding transitions. While root position triads are essential, their overuse can lead to harmonic monotony.

Inverting chords – by changing the bass note and re-ordering the notes – introduces harmonic variety and subtle shifts in stability, resulting in more engaging progressions. (For a deeper dive into B minor chord inversions, see our article “Chords in B Minor: A Comprehensive Guide”. )

Non-Diatonic Chords in a B Minor Key Signature

Beyond the seven diatonic notes of B minor lies a world of harmonic color waiting to be explored. Incorporating all twelve chromatic notes, when used thoughtfully, adds tension, suspense and intrigue, making your music more dynamic and unpredictable.

Mastering all twelve notes, regardless of key, unlocks exciting new expressive possibilities. These non-diatonic notes, which alter a diatonic pitch, are called"accidentals"and are notated with sharps (♯), flats (♭), or naturals (♮) to restore a note to its original diatonic form.

Chromatic notes are particularly useful for:

- Creating harmonic tension and instability

- Smoothing voice leading

- Modulating to new keys

- Deepening emotional impact

- Adding an element of surprise

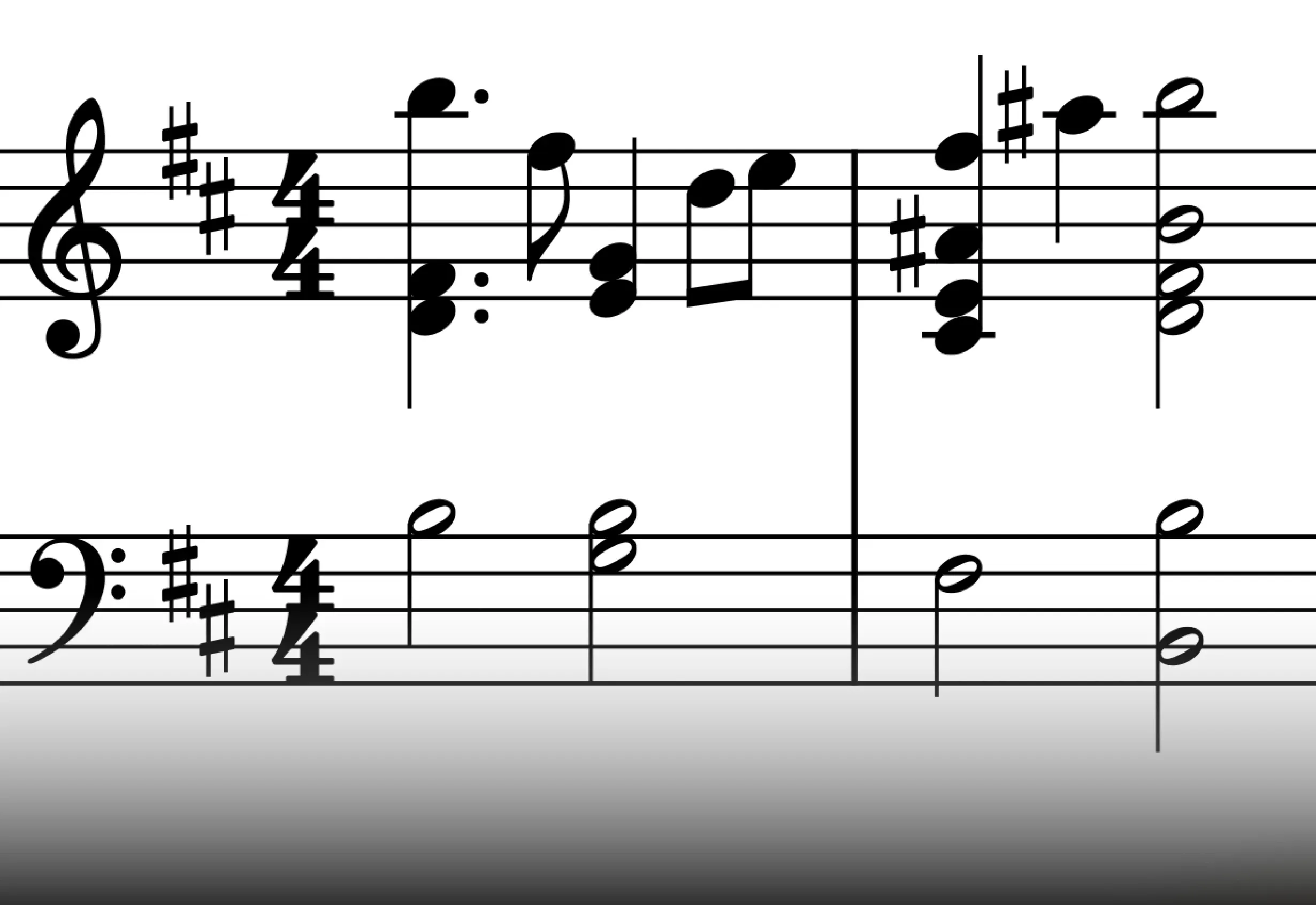

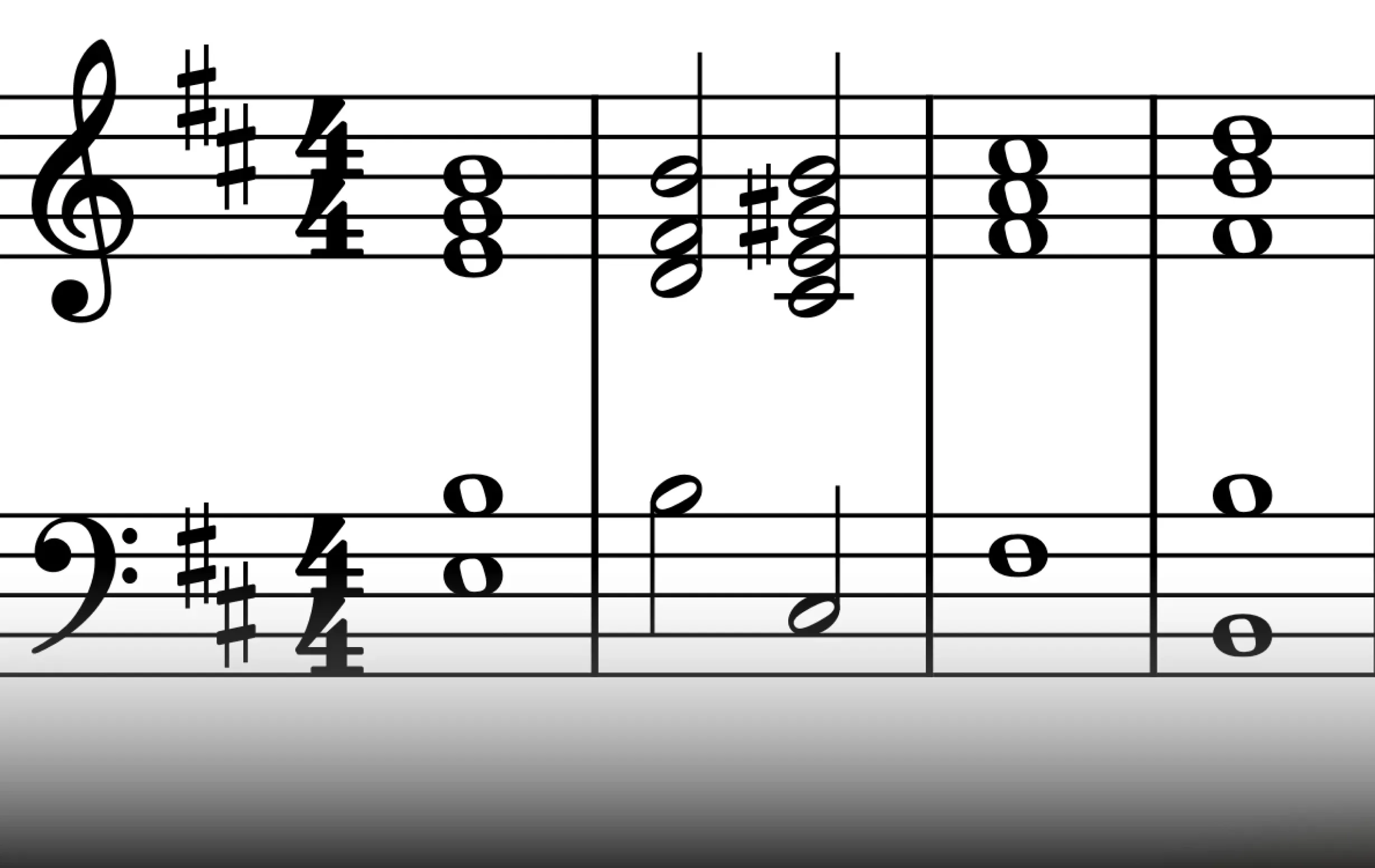

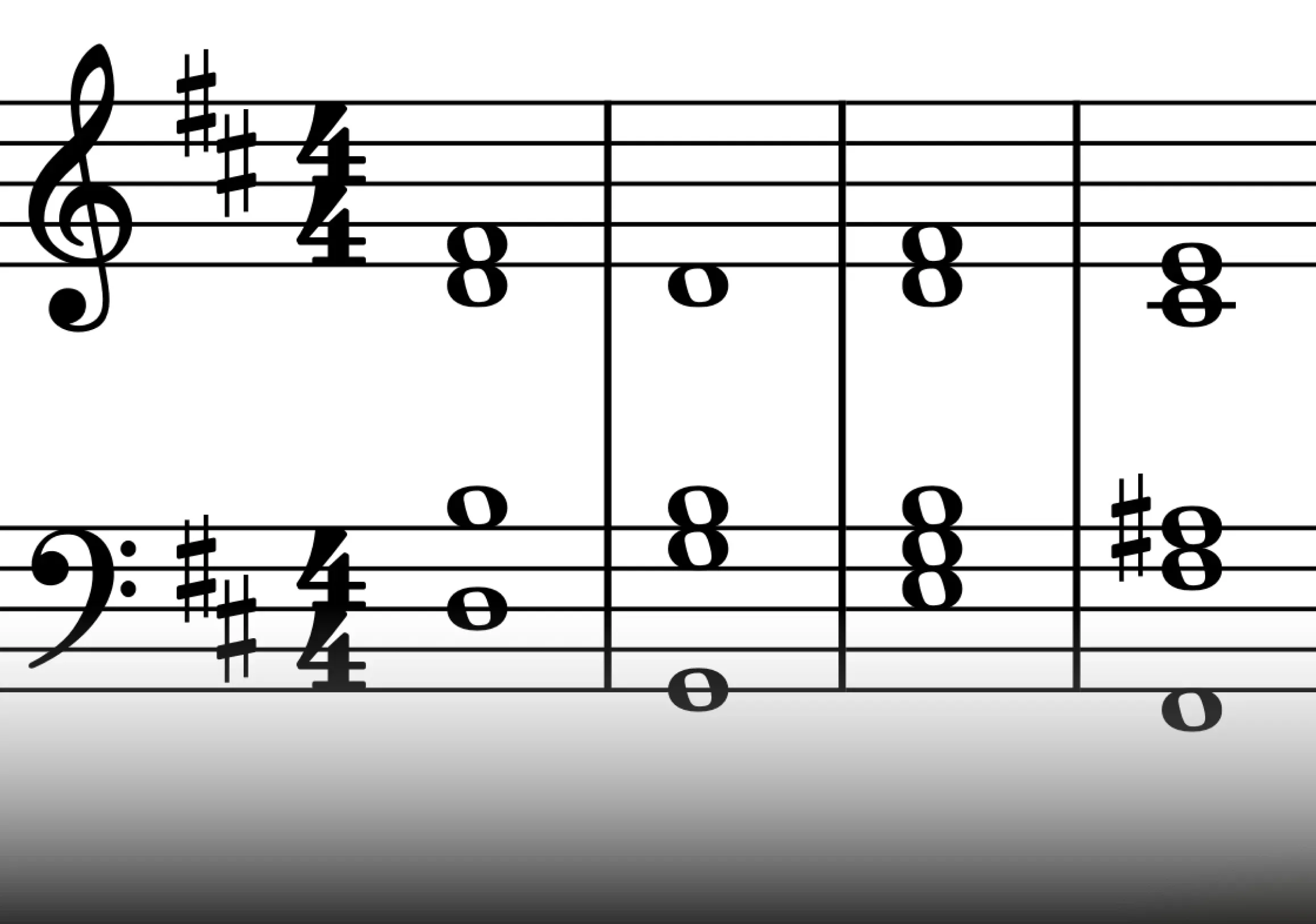

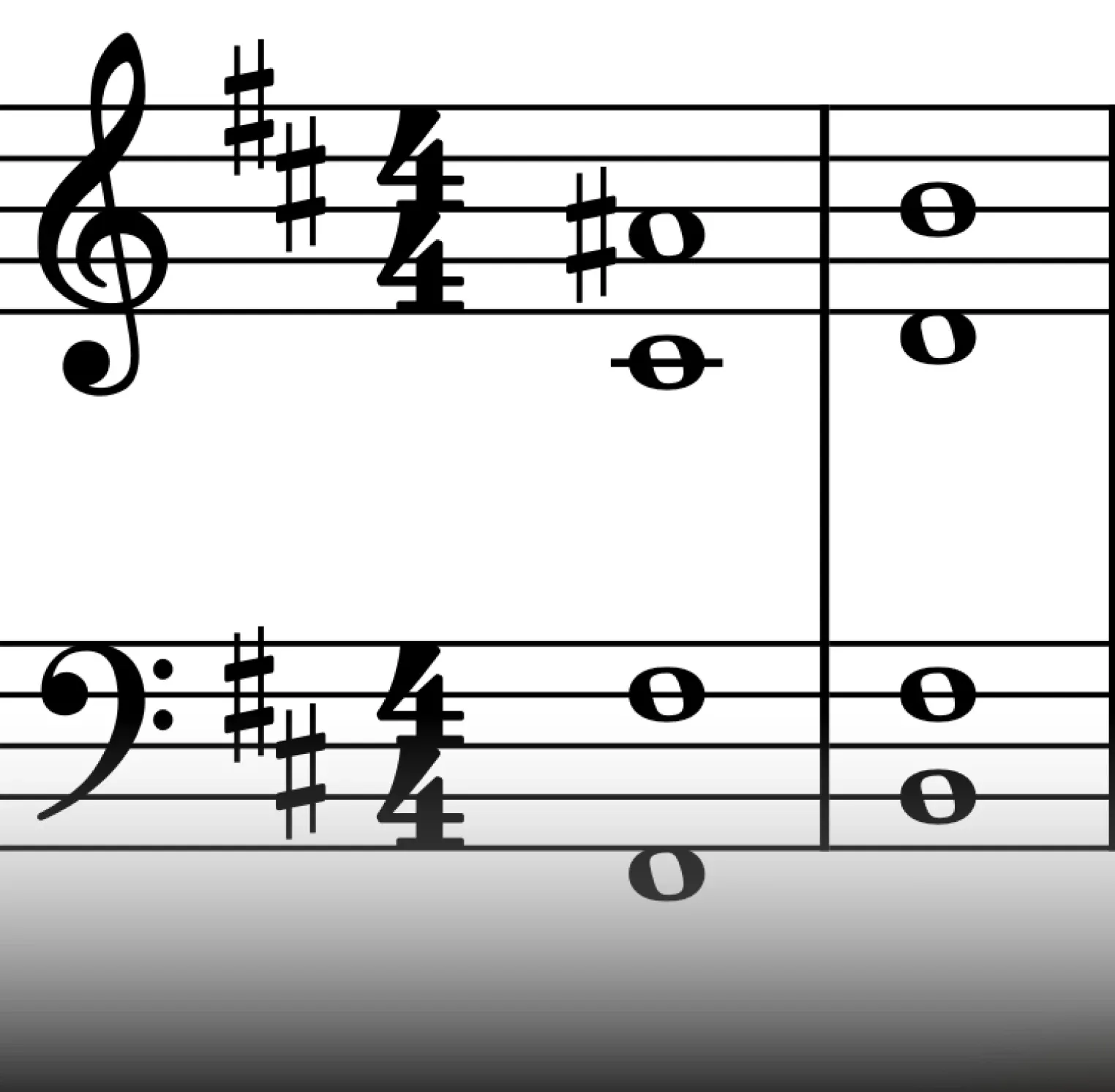

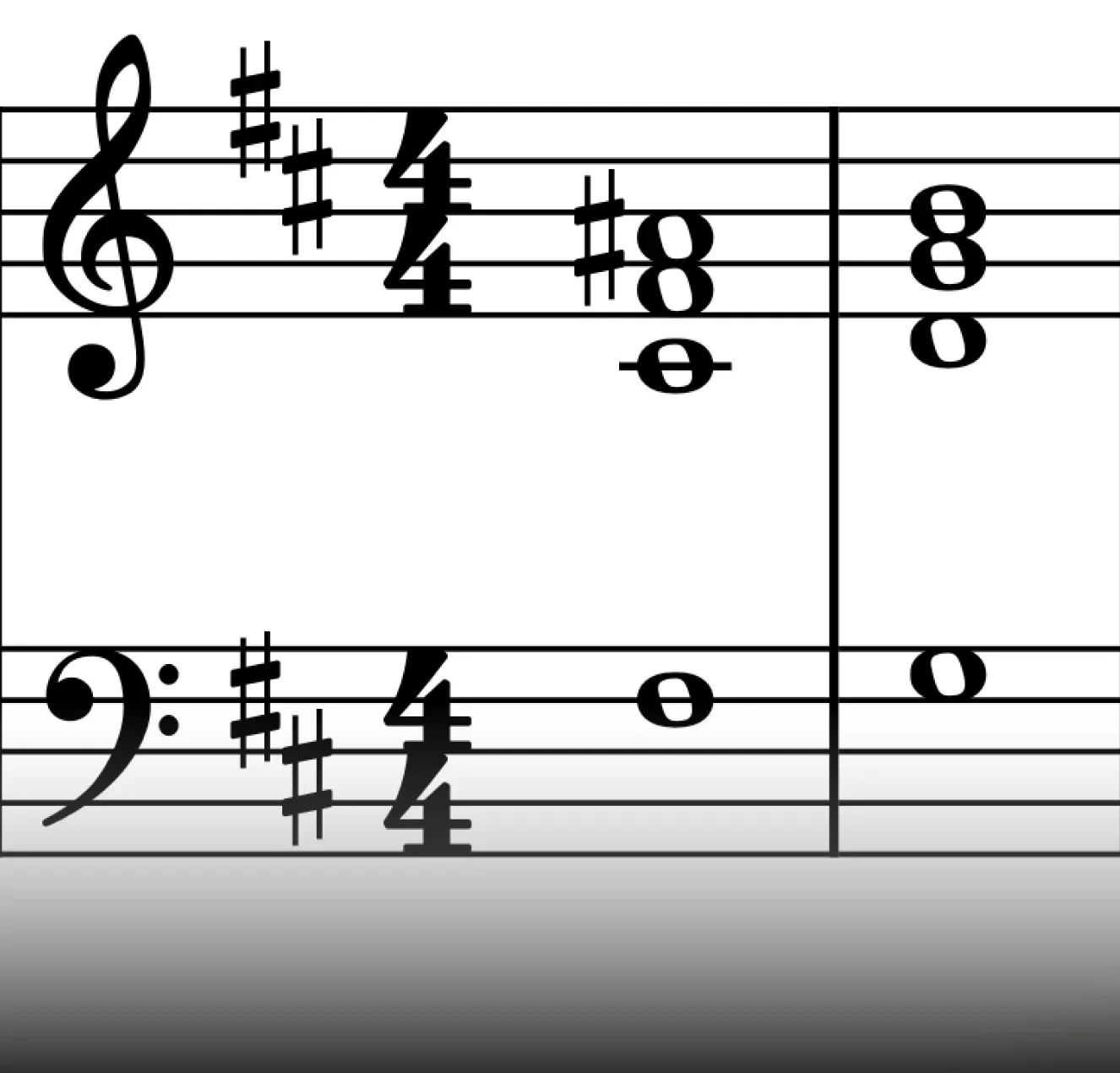

Below is an example of a chord progression and a melody using non-diatonic notes. Notice the symbols used to sharpen the two As.

Chords: Bm - Em/G - F#7 - Bm

Developing your ear for intervals is essential for both composition and improvisation. It allows you to instinctively recognize diatonic and chromatic notes, simplifying the process of choosing the next chord and even facilitating key changes.

A highly effective method for internalizing intervals is associating them with familiar melodies. For more on this, including examples of well-known melodies showcasing each ascending and descending interval, see our article "Ear Training: Songs to Practice Intervals".

Secondary Dominants

In Western harmony, the dominant (the fifth degree of the scale) plays a crucial role. Its inherent tension, resolved by the tonic, forms the powerful dynamic at the heart of dominant-tonic relationships.

This fundamental principle can be extended beyond the basic key through the use of secondary dominants. These chords enable us to temporarily"tonicize"any chord within a key, effectively treating it as a temporary tonic.

This is achieved by borrowing the dominant chord from the key of the target chord. This borrowed dominant, a perfect fifth above the target, becomes the secondary dominant, creating a brief but compelling pull towards the target chord, mirroring the strong resolution of a regular dominant to its tonic.

Let's illustrate the concept of secondary dominants with an example in B minor. Suppose we want to emphasize the subtonic chord, A major, adding harmonic richness to our composition.

While A major is diatonic to B minor, we can heighten its impact by temporarily treating it as a tonic. To achieve this, we introduce its own dominant chord immediately before it. The dominant of A major in this context is E7. Crucially, E7 (E, G#, B, D) contains the note G#, which is chromatic to B minor. This chromatic note is only a half step from the root of A major, which is what gives the secondary dominant its distinctive sound and generates the strong, temporary pull toward this particular target chord.

The E7 chord momentarily creates the impression of being in the key of A major, even though the overall key remains B minor. This"tonicization"adds depth and interest to the harmonic progression.

Secondary dominants allow you to create unexpected harmonic twists and enrich even simple chord progressions. They introduce a layer of sophistication and emotional depth, enhancing musical expression by creating a sense of temporary departure and return within the established key.

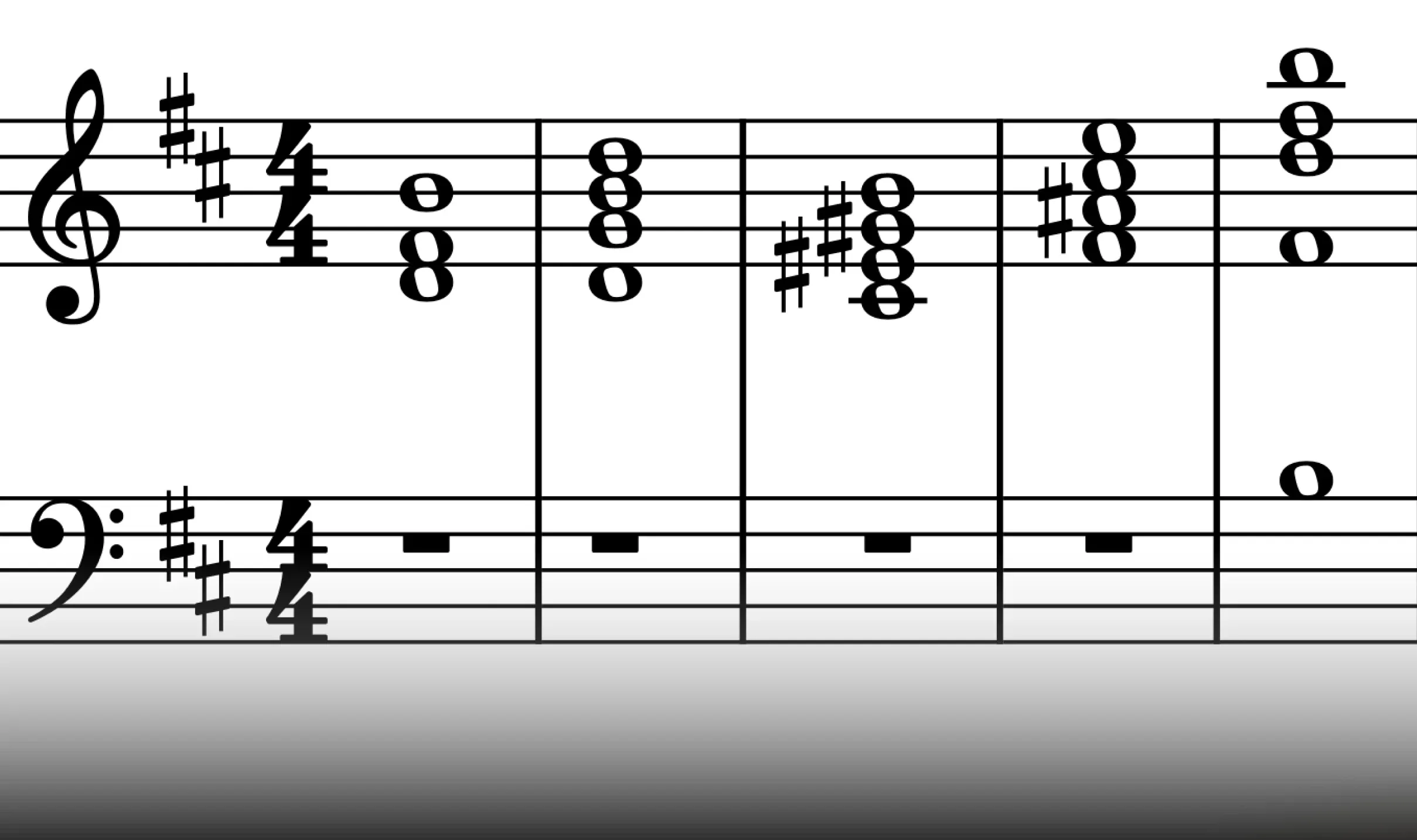

Chords: Bm7 - G - E7 - A - B

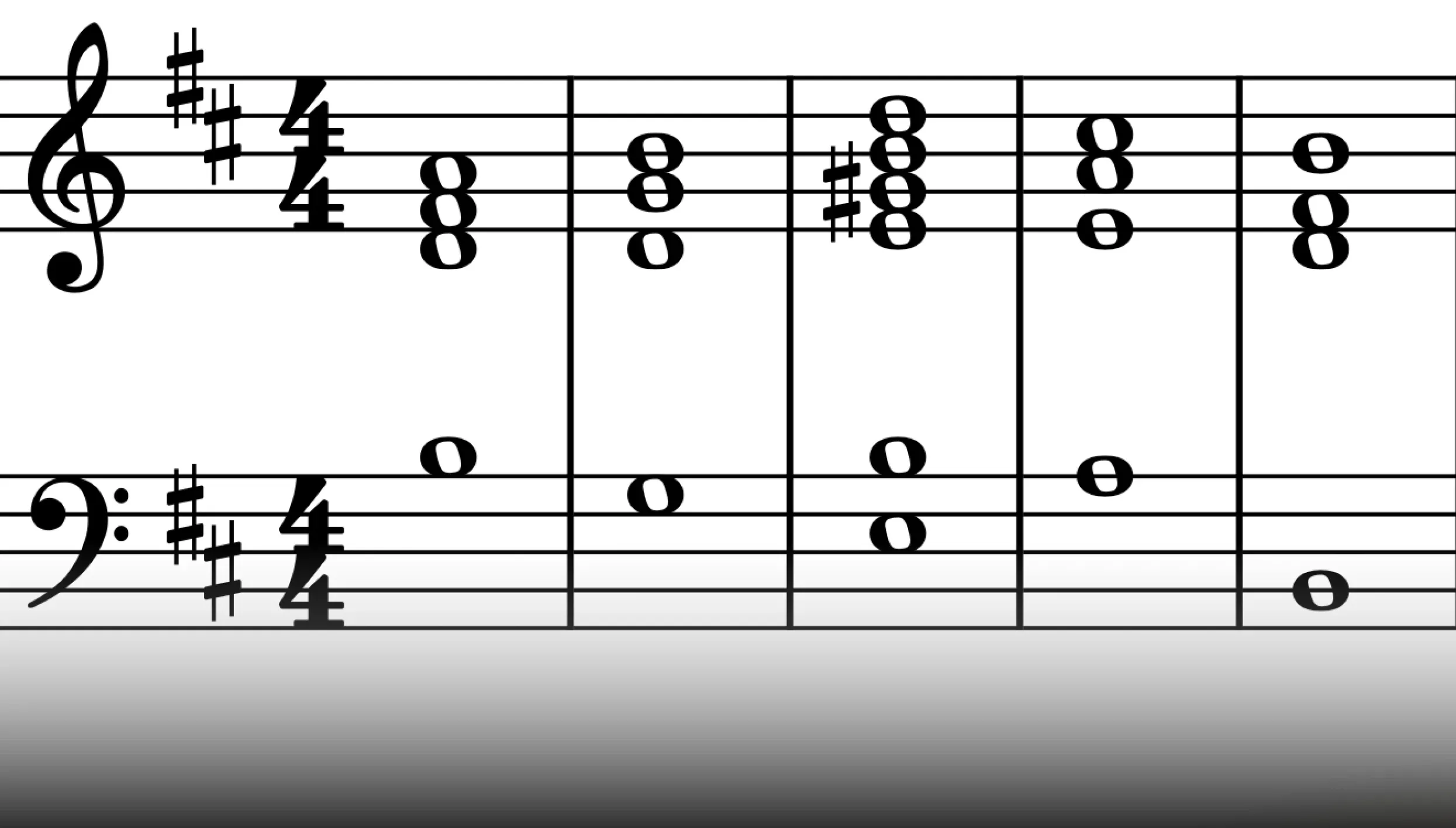

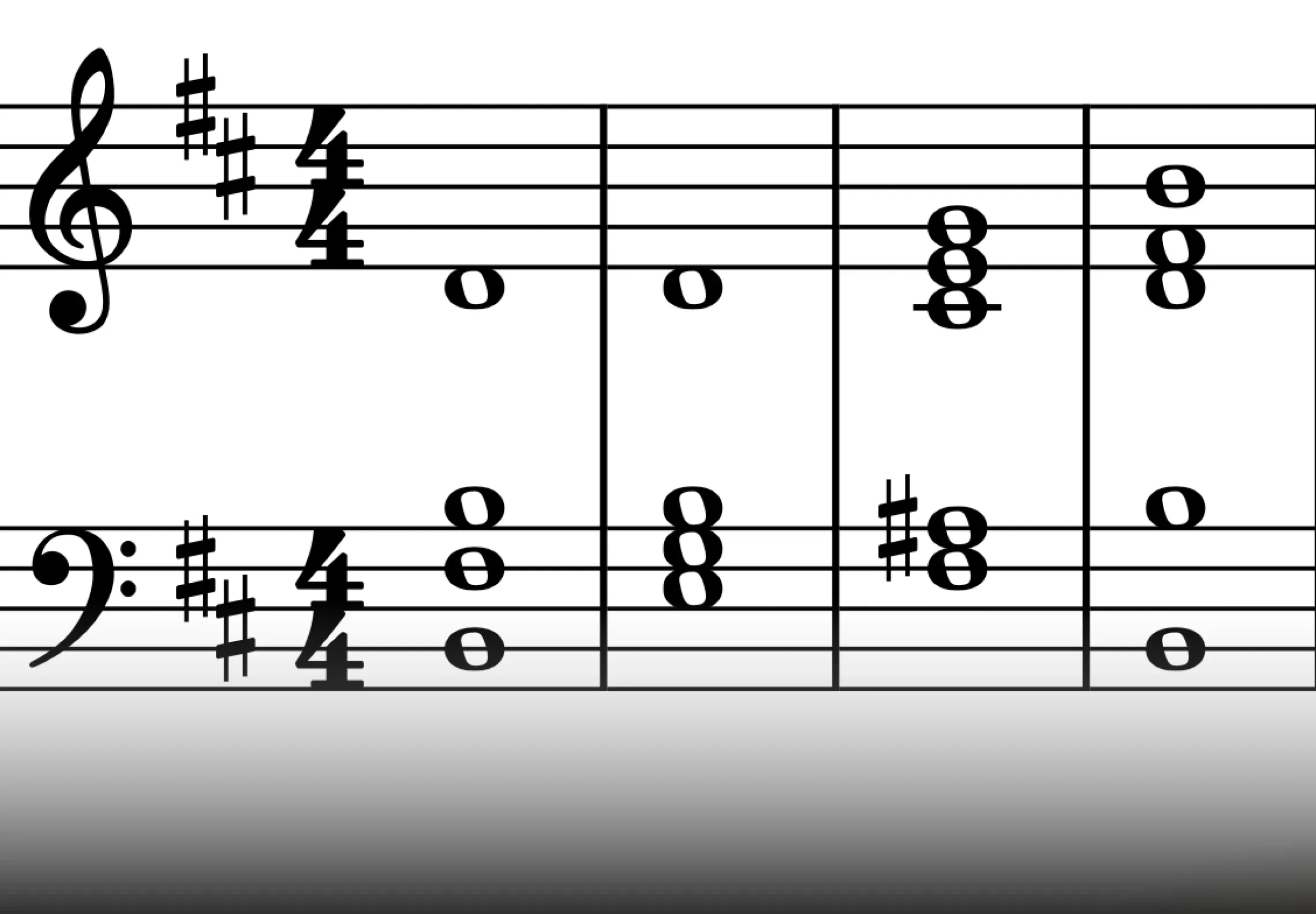

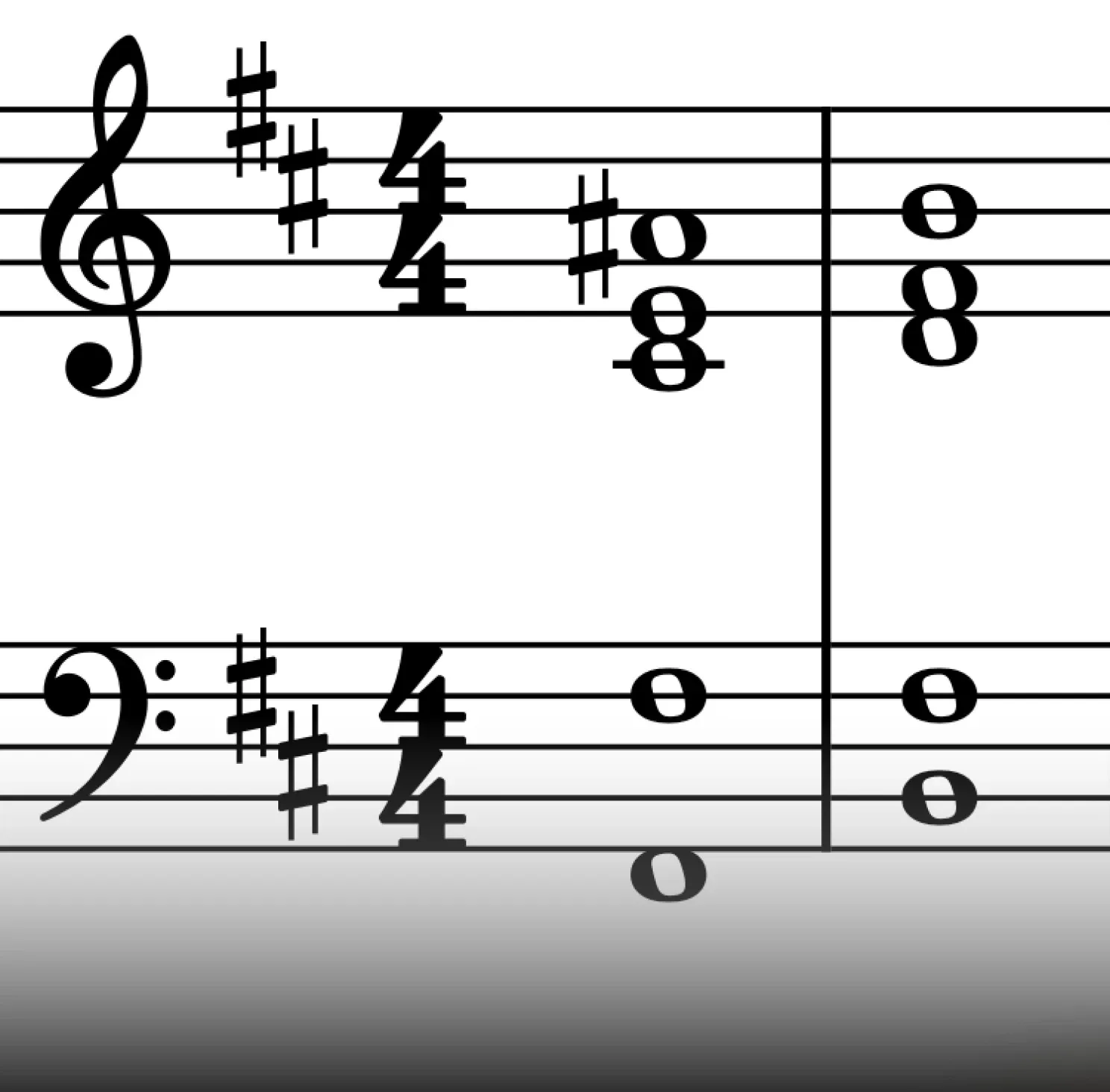

Here's an example of tonicizing the dominant chord by preceding it with its own dominant chord.

Chords: Em - Bm - C#7 - F# - Bm

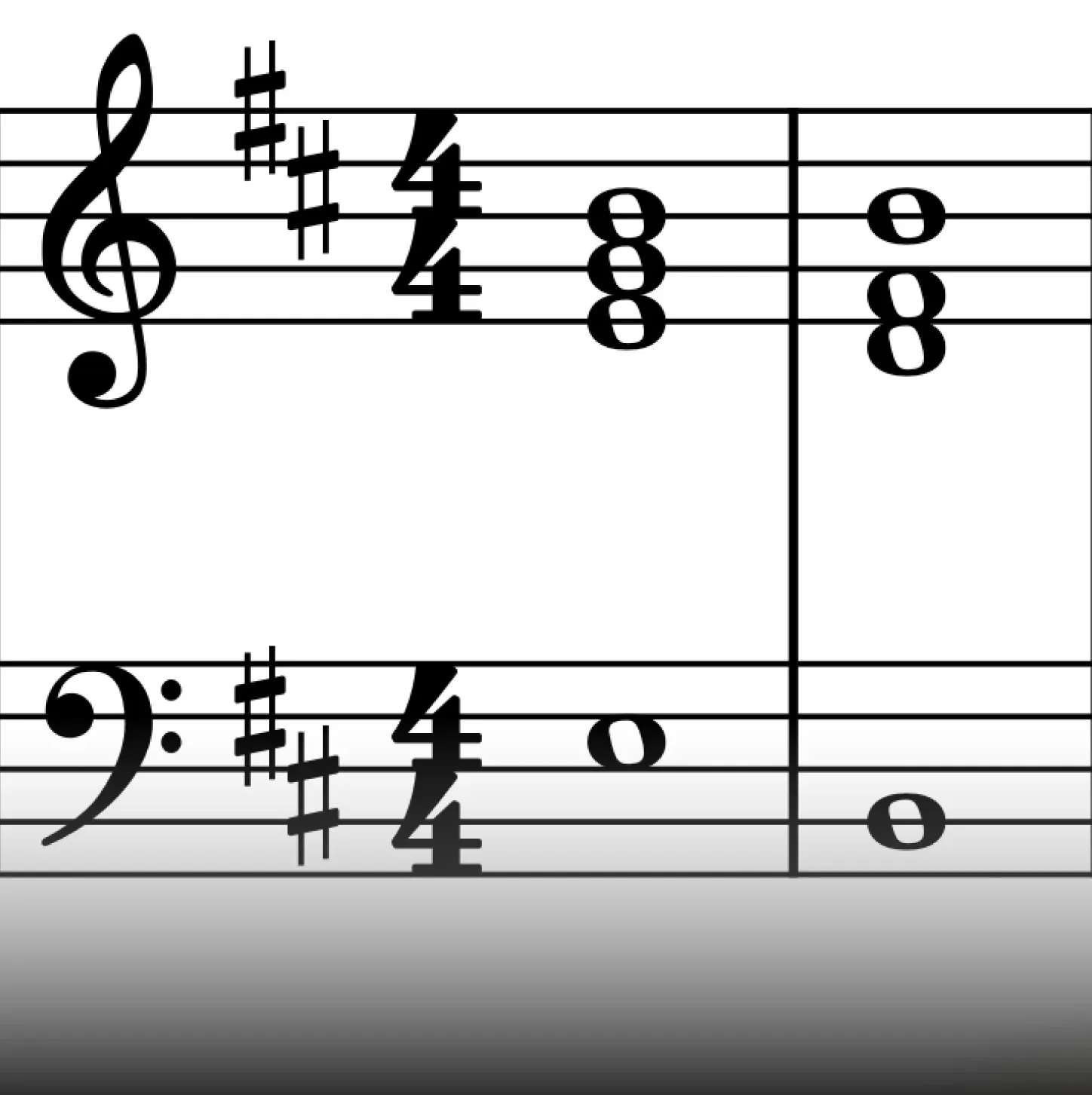

Here’s another example, but with two consecutive secondary dominants.

Chords: Bm - G - C#7 - F#7 - Bm

Chromatic Mediants

Chromatic mediants offer a rich palette of harmonic color and depth. These chords, related to the tonic by a third (major or minor), introduce notes outside the key signature, creating a chromatic effect. Despite this chromaticism, they maintain a connection to the tonic through shared tones.

A chord whose root is a third above or below the tonic is considered a chromatic mediant. Starting from the tonic, move up or down a major or minor third to create chromatic mediants. Keep in mind that the target chord must contain one or two chromatic notes to be chromatic mediants, as opposed to a diatonic mediant. In B minor, examples of chromatic mediants could include an interval from B minor to D minor (a minor third above the tonic), or to G Minor (a major third below the tonic), or chords borrowed from the parallel major key, such as Eb Minor. The defining characteristic is that these chords contain notes outside the B minor scale.

Some theorists stipulate that the chromatic mediant should have the same mode as the tonic. In other words, a minor tonic would lead to a minor chromatic mediant (a third away), and a major tonic to a major chromatic mediant.

The tension between tonal stability and chromaticism makes chromatic mediants particularly compelling. They introduce unexpected harmonic color, enriching progressions and adding depth without ever fully abandoning the tonal center.

This delicate balance keeps the listener engaged and contributes a sophisticated touch. Chromatic mediants are frequently found in film scores, video game music, and other genres where heightened emotion and harmonic interest are paramount, adding a vibrant dimension to the musical language.

The "Imperial March" from Star Wars owes some of its menacing character to the use of chromatic mediants, notably the relationship between the minor tonic and a minor chromatic mediant a third below.

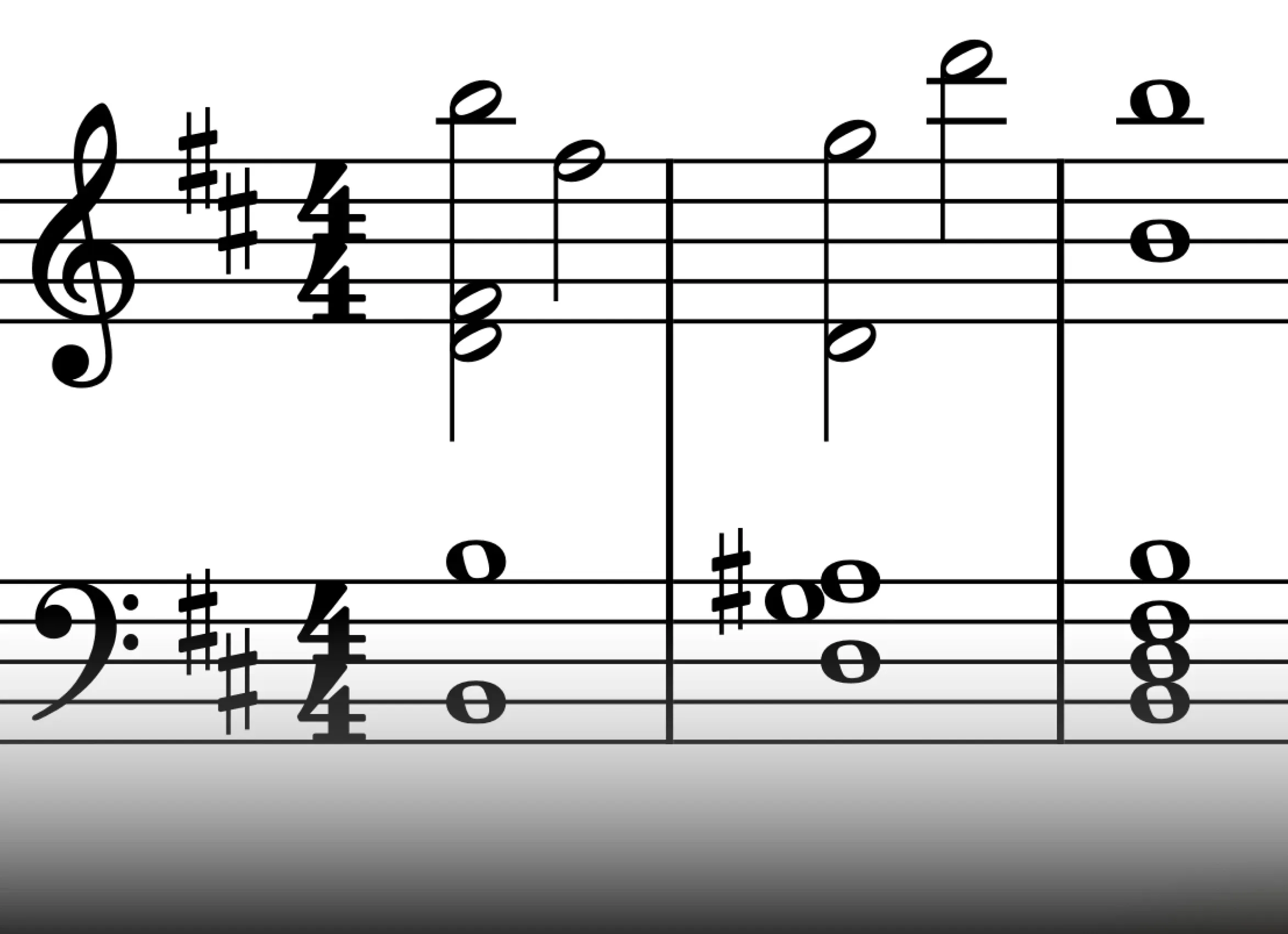

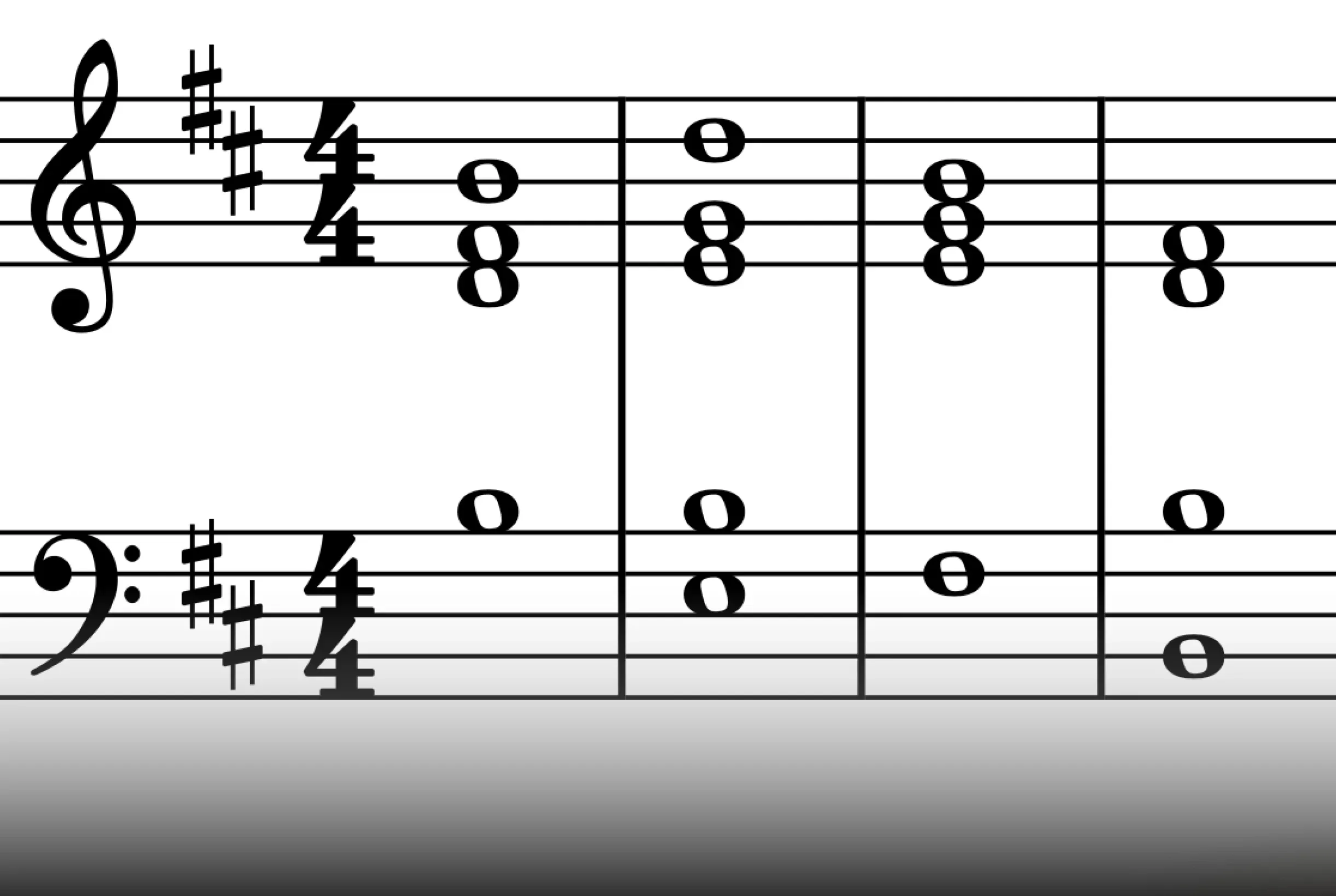

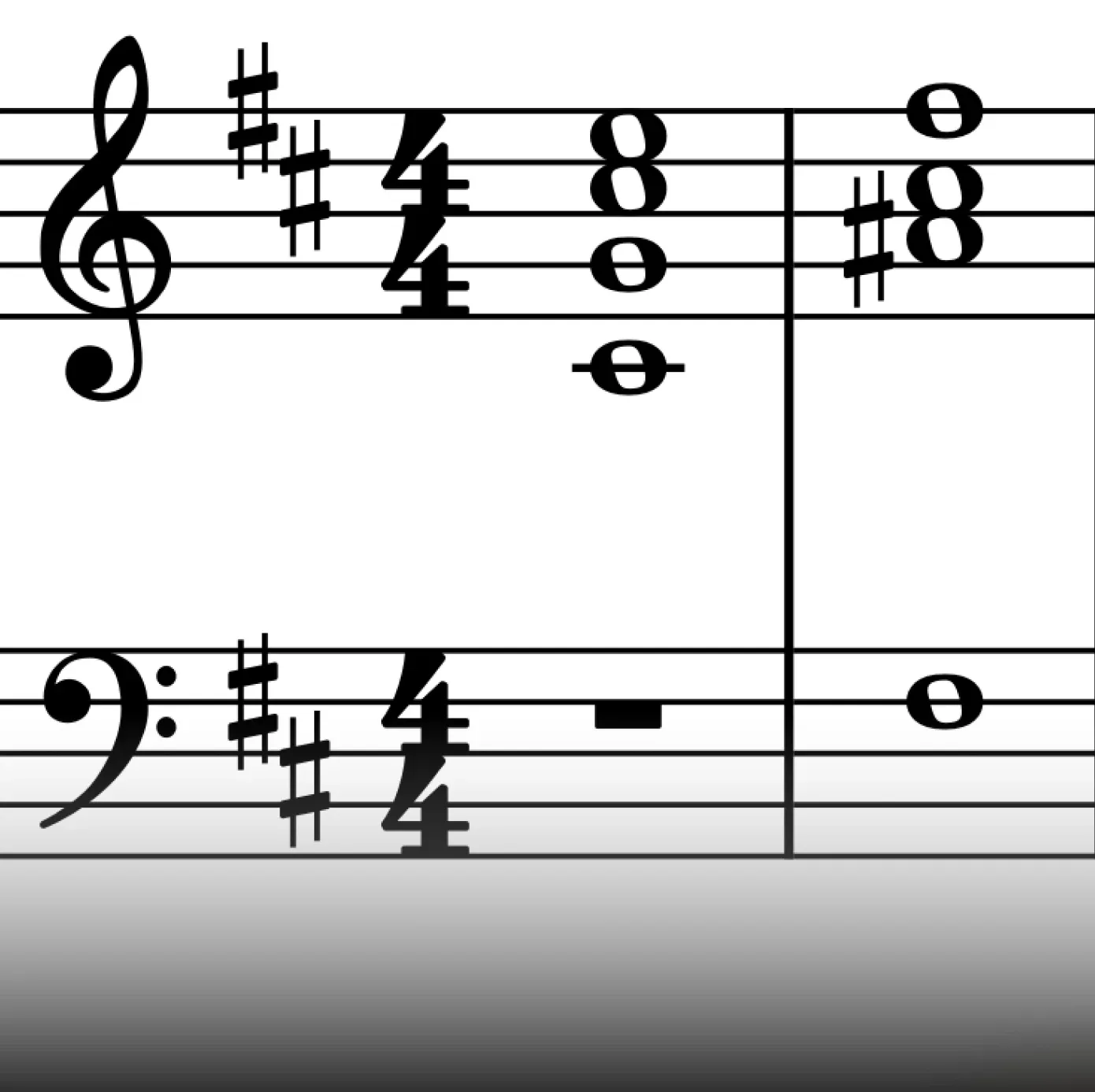

Here are two examples of two chromatic mediants in B Minor.

Chords: Bm - Dm - Em - Bm

In this example, we move from B Minor up a minor third to the chromatic chord D Minor.

In the next example, the tonic moves down by a minor third to G Minor, which is not part of the key signature. This creates a particularly menacing sound, reminiscent of Star Wars and Darth Vader.

Chords: Bm - Gm - Bm

Extended chords

Chord extensions enrich harmonies, adding depth and complexity to music. Starting with a basic triad (root, third, and fifth), adding intervals of a third above the previous note. One added third creates a seventh chord; continuing this process creates ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords.

Just as with seventh chords, these extended chords can be categorized by quality (major, minor, dominant, etc. ), following similar naming conventions.

Although extended chords might initially appear complex, their construction is quite logical. The extension number corresponds to the scale degree above the root of the chord. A 9th, for instance, is the ninth degree of the scale above the chord's root. Likewise, an 11th is the eleventh degree, and a 13th is the thirteenth.

To prevent muddiness, especially in the lower register, chords like the 11th and 13th chords, the third and fifth are often omitted.

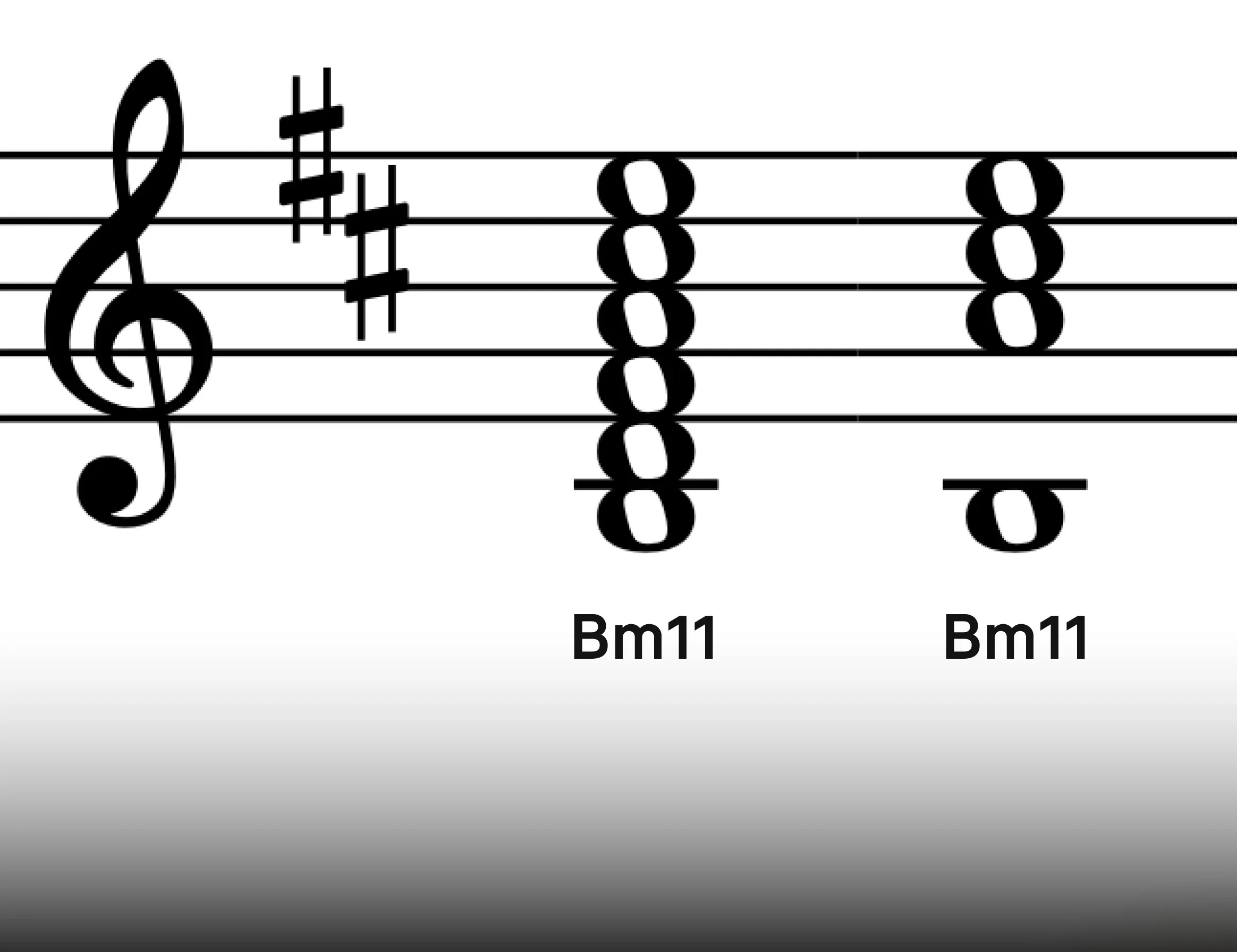

Here’s an Bm11 chord, and by removing the 3rd and 5th, it can be viewed as an A Major triad with a B in the bass. Seeing the chords this way makes them easier to identify. Keep in mind that it functions like the B11 chord.

Ninth Chords

A ninth chord is constructed by extending a seventh chord with another third, following the notes of the scale. In B minor, this means adding a note a third above the seventh of the chord. The resulting ninth chord has a richer, fuller sound compared to both triads and seventh chords.

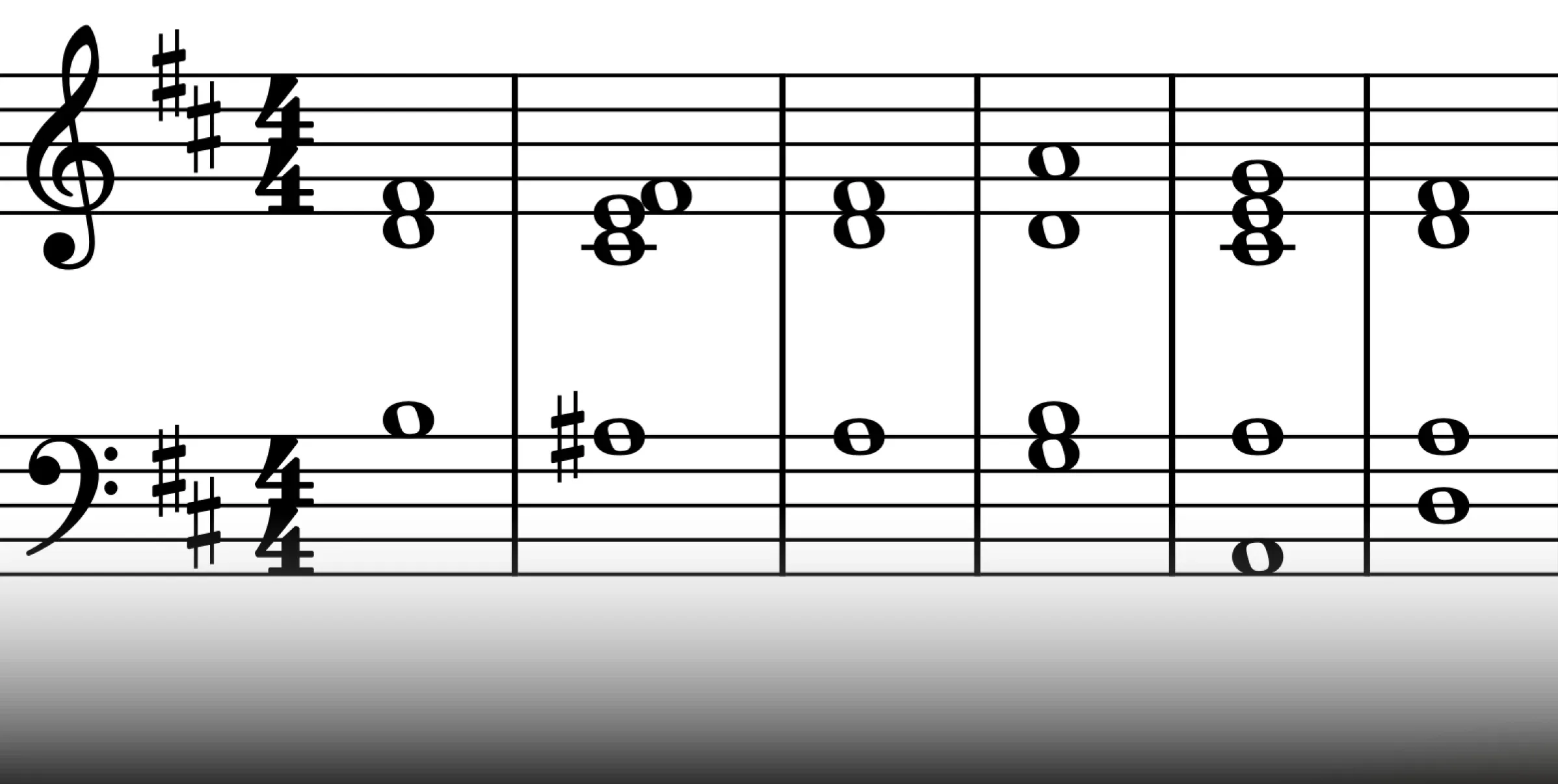

Let’s look at the Minor and B Minor 9th in a chord progression.

Chords: Bm/D - G - Em9 - F#7

Another example is using the Dominant 9th chord.

Chords: Bm - Em7 - F#9 - Bm

Eleven Chords

Adding another third above a ninth scale degree creates an 11th chord; a chord frequently heard in pop music, especially when built on the dominant, due to its characteristic jazzy and soulful sound.

Next is a simple chord progression using the A11 extension in the dominant position, which is commonly found in pop and rock music.

Chords: Bm - Em - F#11 (Em/F#) - Bm

Thirteenth Chords

13th chords, formed by adding yet another third above the 11th, possess a rich and complex harmonic density. Omitting the third and fifth can create a warmer, more spacious sound by reducing the harmonic density in the lower register, allowing the higher extensions to resonate more freely.

The melody in the example below provides chord extensions. This is a way to add harmonic complexity without dense chords.

Chords: Bm - Em - Gmaj13 - F#7

While chord extensions are a hallmark of jazz chord progressions, their use isn't confined to that genre. Pop and rock artists, including Muse and Jimi Hendrix, frequently incorporate extended chords into their compositions, adding depth and harmonic interest.

What’s the Difference Between “B9” and “Badd9”?

In short, “add” chords include only the added note and the basic triad, while numbered extensions imply all notes up to and including the named extension.

Sometimes we want the color of a chord extension without the added harmonic density. That's where"add"chords come in. For chords like Bmadd9, F#add11, or Gmadd13, the 9th, 11th, or 13th degree is simply added to the basic triad, omitting the 7th (and any other extensions below the added note).

A Bm9, F#11, or Dmaj13, on the other hand, implies all notes up to and including the named extension.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

We've already explored the use of chromatic notes through diminished and augmented chords. Delving into notes outside the diatonic scale is a powerful way to introduce unexpected twists and turns, creating more engaging chord progressions.

Experimenting with chromatic chords, passing tones, parallel harmonies, and chromatic mediants can be a valuable source of inspiration, particularly when writer’s block, as they offer a rich palette of unusual harmonic colors that can spark creativity and make you think outside the box.

Relative Major: D Major

Every minor key has a parallel major, and vice versa. These key pairs share the same key signature because they contain the same number and type of accidentals (sharps or flats), but have different tonal centers. This difference in the tonal center is crucial. Even though the keys share the same notes, the feeling and function of chords within each key will be drastically different.

The relative major of a minor key is found on the third scale degree above the minor key's tonic (on the mediant). For example, the relative major of B minor is D major. Conversely, the relative minor of a major key is found on the sixth scale degrees (on the submediant). The relative minor of D major is B minor.

Although relative major and minor keys share the same notes, their tonal centers (D or B in this example) dictate the harmonic role of each chord. Establishing either D or B as the"home"note fundamentally changes how the chords within that shared collection of notes are perceived and used.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

Modulating to D Major, the relative major of B Minor, unlocks a new tonal landscape, offering seven distinct diatonic chord functions – all while remaining within the same key signature. (For a more detailed look at D Major chords, see “Chords in B Minor: A Comprehensive Guide”).

The close relationship between these keys facilitates exciting harmonic interplay. This shift in the tonal center adds depth and allows for contrasting emotional textures between different sections of your music.

Modulation between relative keys is a common and effective compositional technique. For instance, shifting to D Major can create a sense of uplift and positivity, while returning to B minor can evoke a more melancholic mood.

One simple modulation technique involves identifying a diatonic chord to both keys. For example, A Major is the VII chord in the B Minor key signature, and the V chord in D Major. In the example below, the A Major is used as the pivot chord from B to D, creating a V-I progression in the relative major key (A7 - D Major).

Chords: Bm - F#7/Bb - D/A - Gadd9 - A7 - D

Parallel Chords

Parallel chords, created by altering a chord's mode (major or minor) by adding accidentals, offer a way to introduce unexpected harmonic twists. For example, in a B minor progression, transforming the submediant (G major) to G minor (by lowering the B to Bb) creates a distinct emotional shift.

This technique can surprise the listener and subtly alter the mood of a piece. A common application is the use of the major tonic – B Major in the key of B Minor – can create a contrast to the prevailing minor tonality, adding a moment of brightness or resolution.

While parallel chords can be a powerful tool, they should be used carefully. Overuse can destabilize harmony and create a sense of aimlessness by weakening the established tonal center. Strategic placement, however, can emphasize key moments and enhance the overall tonal richness of a song.

Cadences in B Minor chord progressions

Just as punctuation shapes and emphasizes language, cadences provide structure and emotional impact in music. They act as musical punctuation, defining the emotional arc of a phrase. By varying cadences, composers and producers can create a wide range of expressive effects, from powerful climaxes to gentle, reflective endings.

Below, we'll explore common cadences in B Minor.

Perfect Cadence

The classic V-i cadence provides a strong, familiar sense of resolution, effectively concluding a musical phrase or an entire piece. This clear and decisive ending creates a feeling of musical closure.

A perfect (or authentic) cadence has two key requirements: both chords must be in root position, meaning the root of each chord is the lowest note, and the highest voice of the tonic chord must also be the root. These conditions ensure the strongest possible resolution.

Dominant → Tonic (V - i)

F# → B Minor

The tonic can be resolved with a dominant seventh chord to create an even stronger resolution.

F#7 → B Minor (V7 - i)

Plagal Cadence

In contrast to the definitive resolution of a perfect authentic cadence, the plagal cadence, sometimes referred to as the "Amen" cadence, offers a more gentle conclusion. This less assertive quality makes it a popular choice in traditional hymns, where the iv-i progression often accompanies the closing "Amen”.

Subdominant → Tonic (iv - i)

E Minor → B Minor

Half Cadence

While perfect authentic and plagal cadences provide closure, the half cadence offers a different effect: it concludes on the dominant chord, creating a sense of expectation rather than resolution.

This feeling of harmonic incompleteness is a powerful tool for building anticipation. This unresolved tension makes the subsequent tonic resolution even more satisfying, adding a sense of forward drive and contributing to the overall dynamic shape of the music.

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (i / ii° / iv → V)

B Minor→ F#

C# Diminished → F#

E Minor → F#

Interrupted Cadence

The interrupted cadence, also known as a deceptive cadence, sets up an expectation of a strong, definitive resolution, only to veer unexpectedly to the submediant chord. This harmonic surprise creates a sense of delayed gratification and can be used to smoothly transition to a new tonal center, especially the relative minor from a major key.

Dominant to Submediant (V - VI)

F# → G Major

Aim for Stability In Your B Minor Chord Progression

Diatonic harmony, while seemingly simple with its seven diatonic triads (and inversions), offers a surprisingly rich palette of expressive possibilities. Compelling progressions can be crafted using only these basic building blocks.

While harmonic theory can delve into complex intricacies, a solid foundation in diatonic chords provides a strong starting point. Stability is often key, as it provides a strong foundation for building more complex harmonic structures and creating a sense of tonal grounding.

Traditional theory categorizes diatonic chords as primary and secondary. The primary chords – i (B minor), iv (E Minor), and V (F# Minor and Major) – form the harmonic foundation, creating a balanced interplay of tension, anticipation, and resolution. These are the chords that establish the key and provide a sense of tonal grounding.

The secondary chords – ii° (C# diminished), III (D Major), VI (G Major), and VII (A Major) – offer contrasting moods and add color and complexity to the harmonic landscape. Analyzing song structures often reveals a strategic emphasis on the primary chords, with secondary chords used to create points of interest and harmonic variety.

Extended chords and accidentals should be used thoughtfully. Their power lies in their ability to create moments of heightened color and drama, but overuse can destabilize the harmony and create a sense of disorientation. Purposeful use is essential for maintaining clarity and impact.

Musiversal: For Musicians, by Musicians

Elevate your music by remotely collaborating with professional musicians. Musiversal connects you with a network of over 100 talented artists and engineers, all accessible with a single click. Our Unlimited membership unlocks a world of possibilities, giving you unlimited recording sessions with top-tier professionals.

Whether you need a specific instrument or a particular artist, Musiversal has you covered. Join your recording session virtually and collaborate in real-time, ensuring your creative vision is brought to life. Our extensive roster includes drummers, cellists, guitarists, string players, pianists, wind instrumentalists, bassists, beatmakers, songwriters, and much more.

Schedule a session with your chosen artist at your convenience and witness your musical ideas blossom in real-time.

Even if you only have a musical idea, and not a song ready for recording, our songwriting sessions provide collaborative support to develop it into a complete song - or to refine and perfect a work in progress.

Already have finished tracks but need that professional polish? Our mixing and mastering engineers can give your music the final touch, ensuring it's release-ready.

For valuable insights into music theory, songwriting, creativity, production, gear, marketing, and distribution, check out the Musiversal Blog, updated weekly.

[CTA:community]

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist