Learn Chords in D Major: Functions, Tips, and Examples for Beginners

Discover how to learn D Major chords, their role in music theory, and how to use them in your own compositions. Perfect guide for beginners and musicians.

Introduction

Knowing which chords are available in any key will simplify things for any musician and producer. Also, understanding why we can use these specific chords is equally important. This knowledge will enable you to write music faster and with more purpose.

This article will explore the chords in D major. We’ll start by covering the basics of the D major scale before diving into triads in D major. Lastly, we'll look at non-diatonic chords such as augmented and diminished chords, as well as suspended chords.

In this article, you'll get a step-by-step guide to the chords in D major, exploring how to use them effectively in your music. You'll also learn how to incorporate each chord into compelling and dynamic progressions to enhance your sound by learning about chord functions.

You’ll learn:

- the basics of music theory for D Major scale

- the chords for D major and their harmonic functions

- how to alter chords using non-scale tones for more sophisticated harmony in your music

The Basics of the D Major Scale

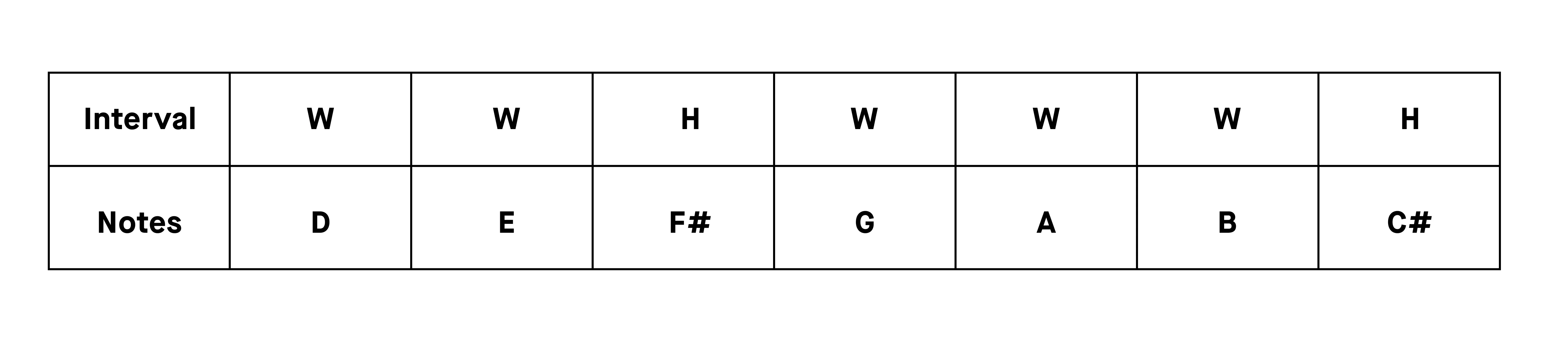

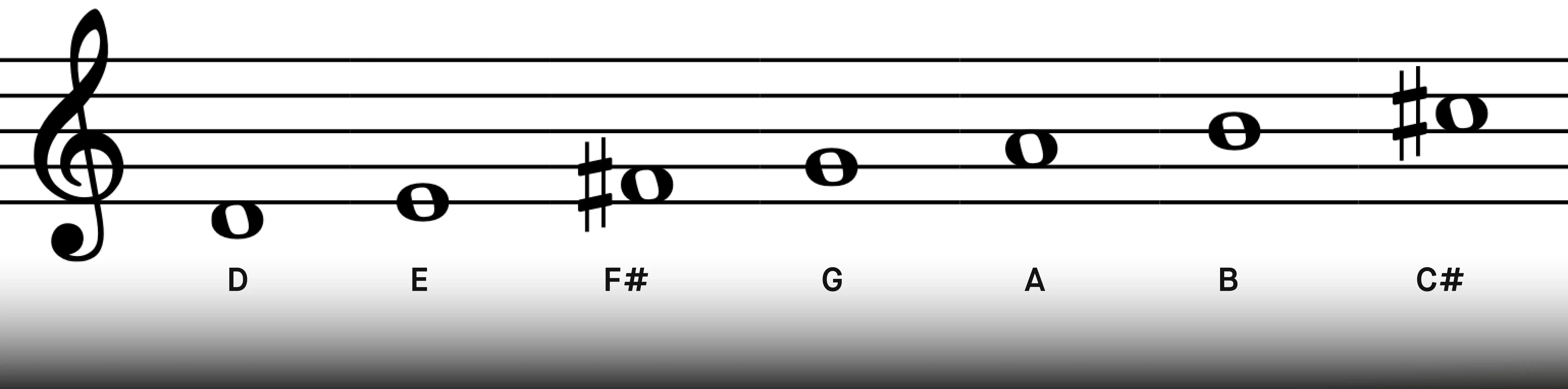

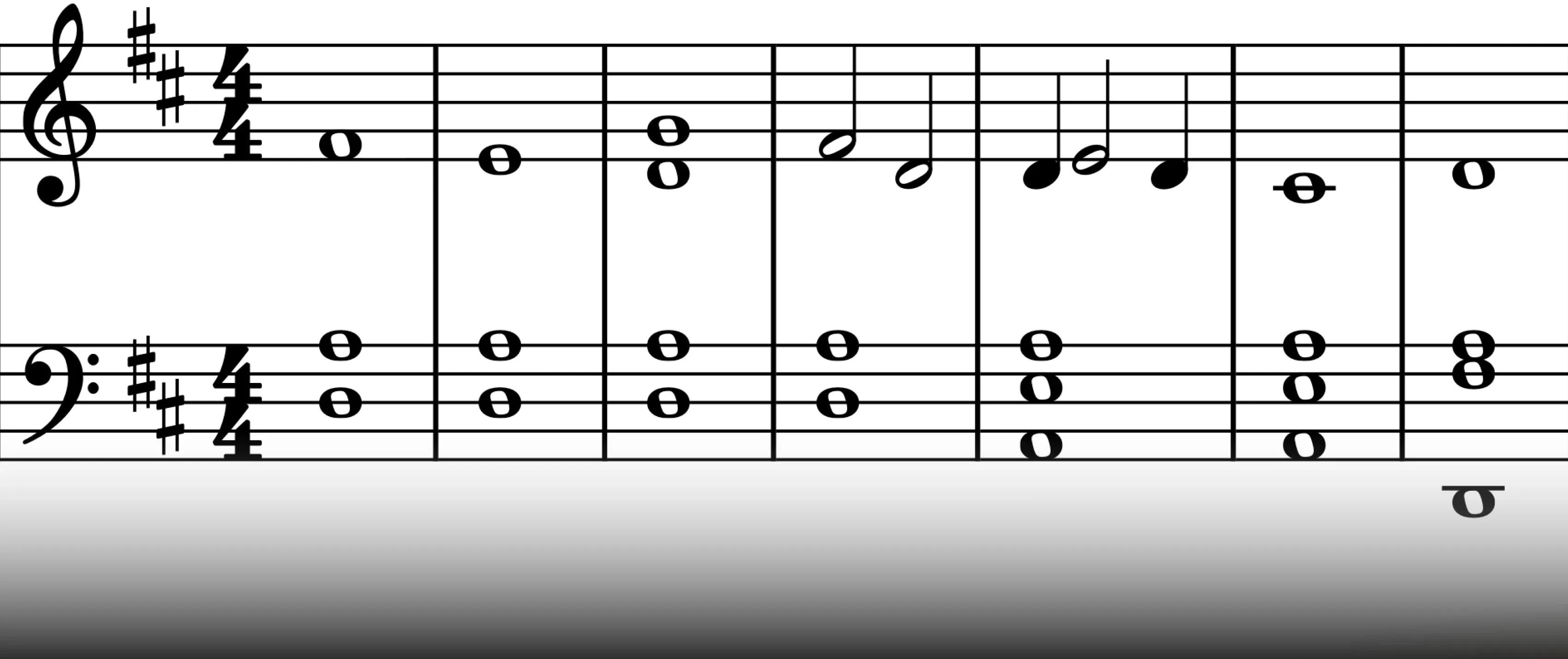

The D major scale consists of seven notes, which form the basis for building D Major chords and progressions in music theory. The seven diatonic notes (D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#) come from following a specific pattern of whole and half steps.

This pattern of whole steps and half steps is called the Ionian mode but is also known simply as the “major scale”. If you're not familiar with music modes, check out Charles Cornell’s video for a clear, interesting, and engaging explanation.

The D Major scale, like any major scale, is built on seven distinct notes, each a specific distance from the tonic (D in this case). These positions are called scale degrees, and each one plays a unique role in creating chords and harmony.

Roman numerals are used in music theory to represent these scale degrees and the chords built upon them. Uppercase Roman numerals indicate major chords, while lowercase Roman numerals indicate minor chords.

Here's how the notes of the D Major scale relate to their scale degrees, and how those degrees are named and represented with Roman numerals:

- D - Tonic (1st degree) - I

- E - Supertonic (2nd degree) - ii

- F# - Mediant (3rd degree) - iii

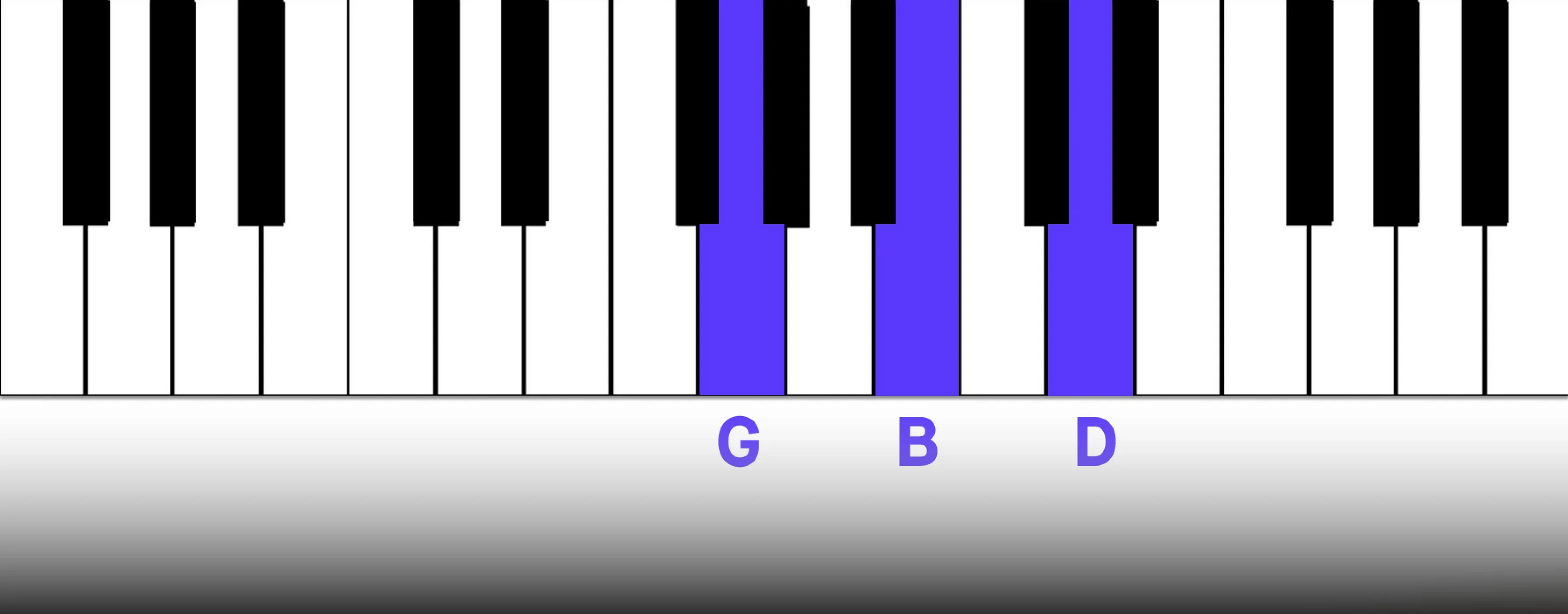

- G - Subdominant (4th degree) - IV

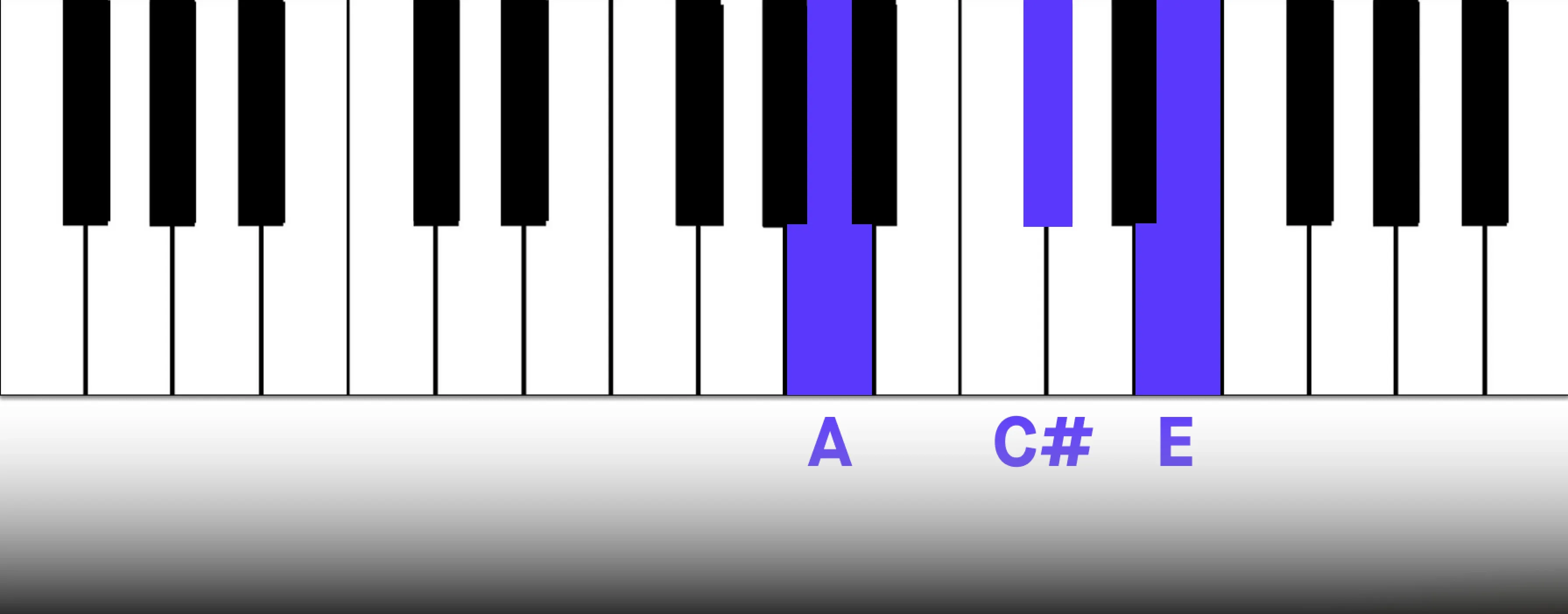

- A - Dominant (5th degree) - V

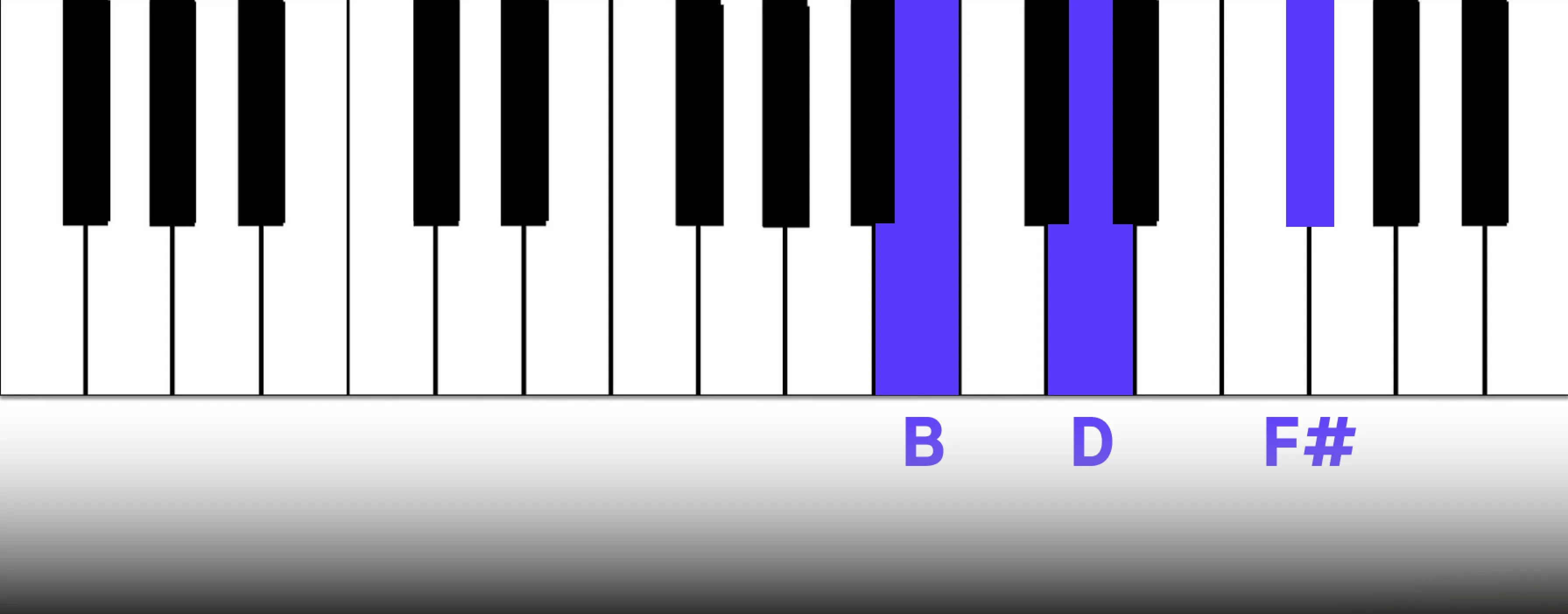

- B - Submediant (6th degree) - vi

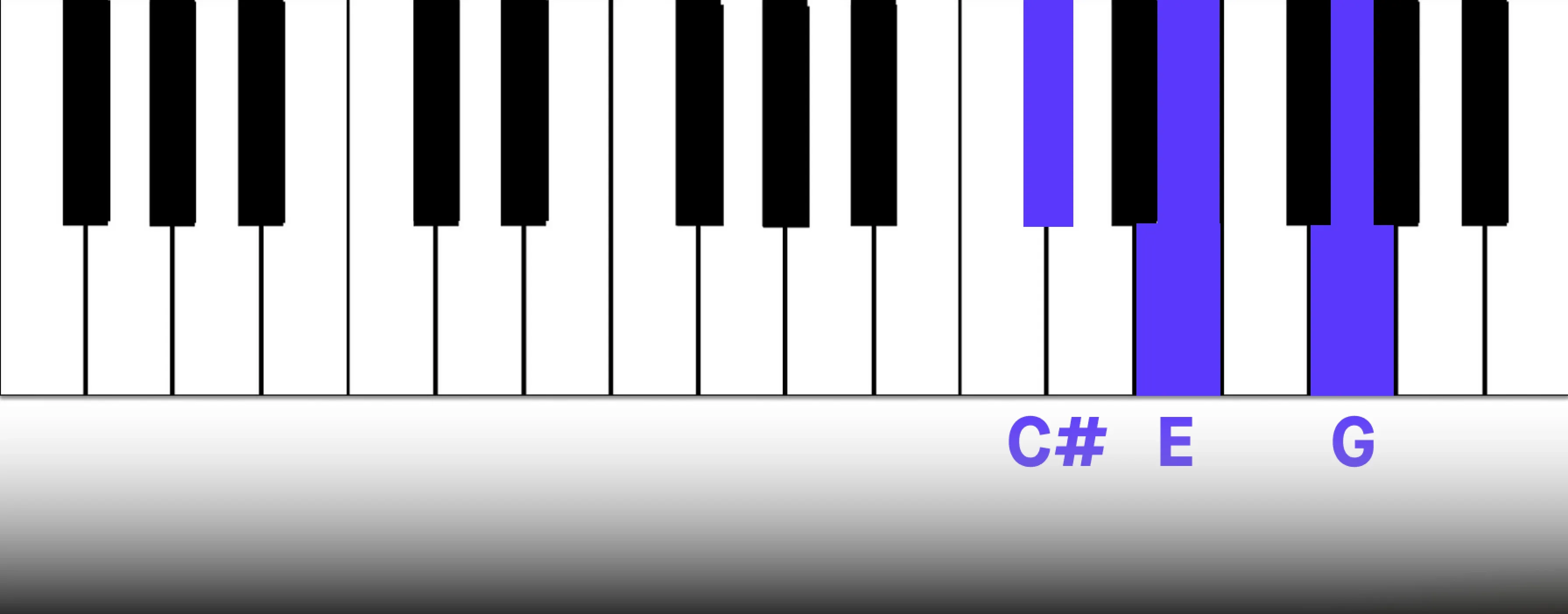

- C# - Leading Tone (7th degree) - vii° (diminished chord)

If you want to explore beyond D Major, our blog offers in-depth coverage of all key signatures.

D Major Chords and Their Functions in Music

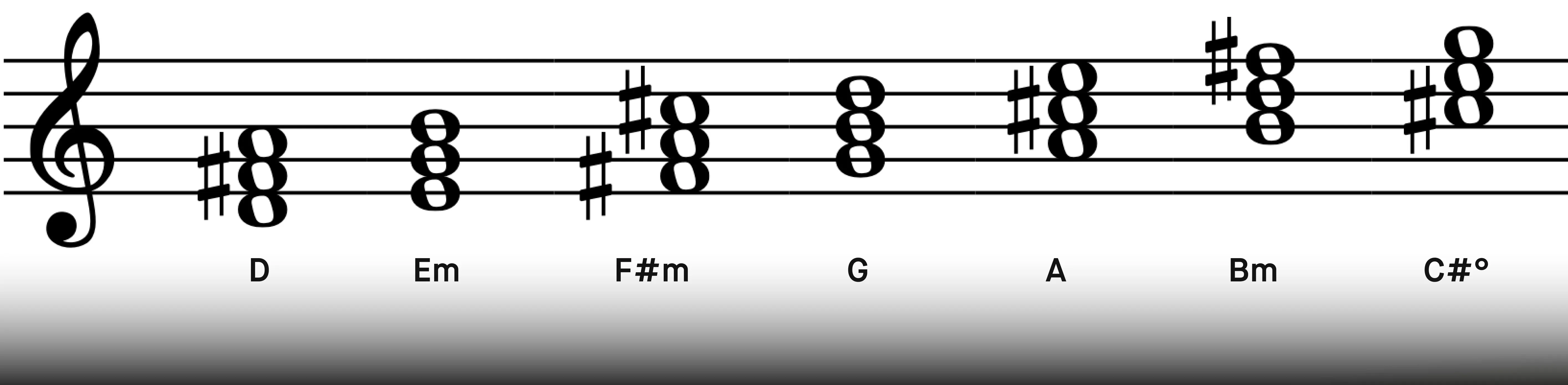

How to build chords in D major? The most common chord type, the triad, is comprised of these three notes: the tonic, the third, and the fifth. A chord's root is its tonic, which gives the chord its name. The third determines the chord's quality (major or minor) and the fifth adds harmonic richness.

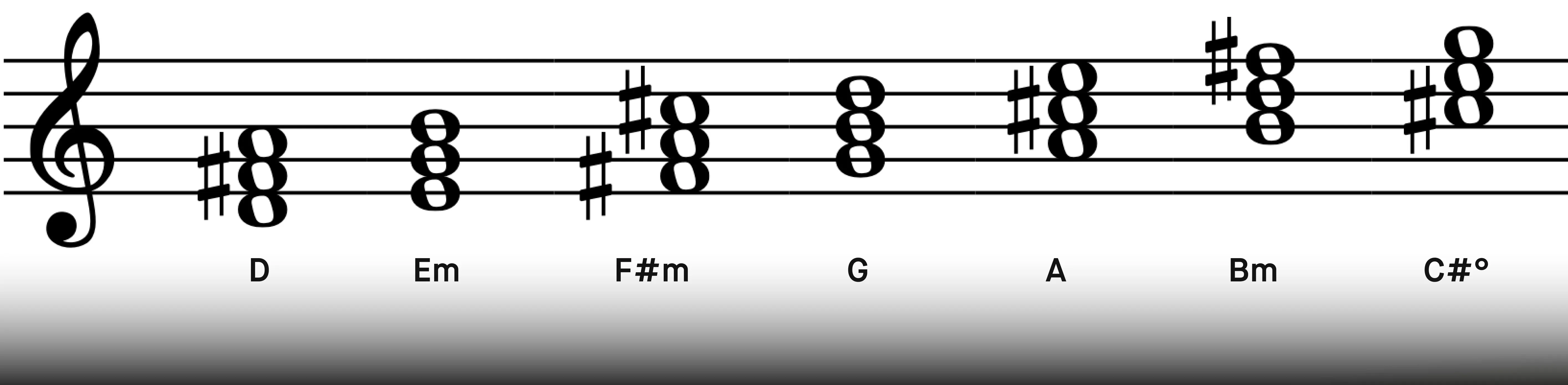

The 7 diatonic chords in D major are: D Major, E minor, F# Minor, G Major, A Major, B Minor, and C#°.

In this section, we’ll look at the chords in D major, as well as common approaches to using each chord within the harmonic context of a song.

This section explores playing chords in D major on piano, analyzing their functions, and examining common approaches to using each chord within the harmonic context of a song. The visual layout of a piano makes it easier to understand chord construction and quickly identify alterations, such as those in an augmented chord.

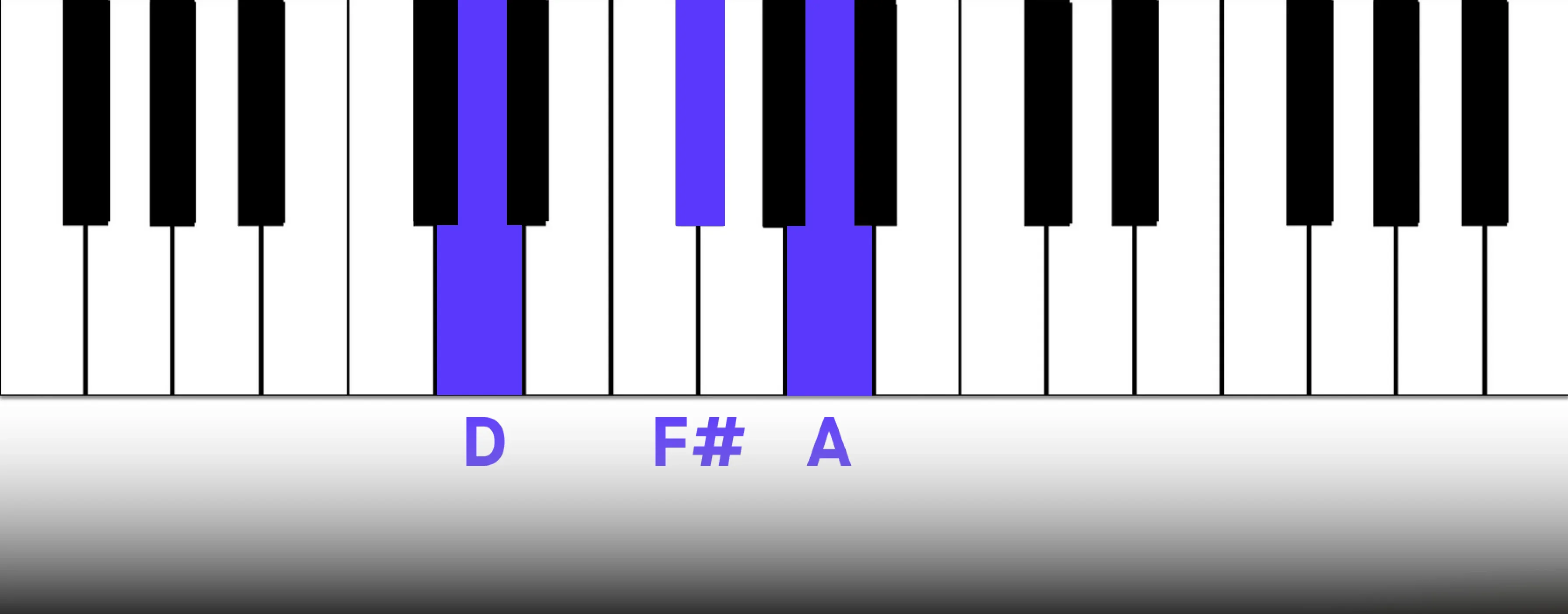

I: D Major

The D Major chord, the tonic chord, is the foundation of the D Major scale and key. As the most stable and grounded chord, it provides a sense of resolution and rest. Unlike other chords in the key, the tonic chord doesn't inherently need to resolve elsewhere.

For example, ABBA's"Mamma Mia"prominently features the tonic chord, showcasing its central role. Both the verse and chorus begin in D Major. The pre-chorus is particularly interesting because it avoids D Major, creating a sense of anticipation that is then resolved by the impactful return to the tonic chord in the chorus.

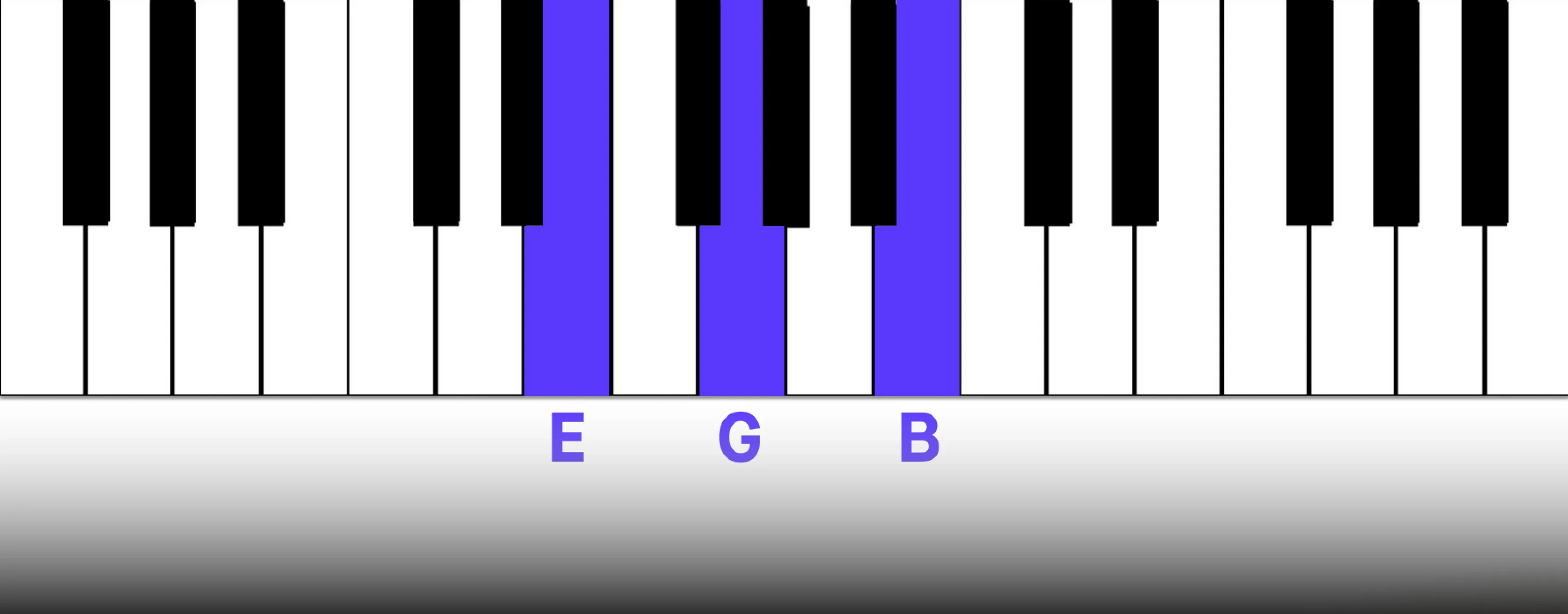

ii: E Minor

The E minor chord, the supertonic, has several functions. It can act as a pre-dominant chord, leading to the dominant and creating harmonic tension. It can also create a smooth transition to the tonic, providing a seamless resolution.

Example: In “Our Song” by Taylor Swift, she uses the supertonic to create an ascending line in a 4-chord progression, using the chords I-ii7-IV-V.

Oasis’ “Stop Crying Your Heart Out” uses minor ii as the primary minor color in an I-V-ii-IV-I progression.

The pre-chorus of Ed Sheeran's"Thinking Out Loud"utilizes an E minor chord to differentiate it from the major-centric verse. This subtle shift to a minor chord creates a more melancholy mood and adds emotional depth.

In jazz, the minor ii chord plays an important role in the popular ii-V7-I progression, where it sets up movement toward the dominant which then resolves back to the tonic. For more information about jazz chords, see our article covering jazz chord progressions.

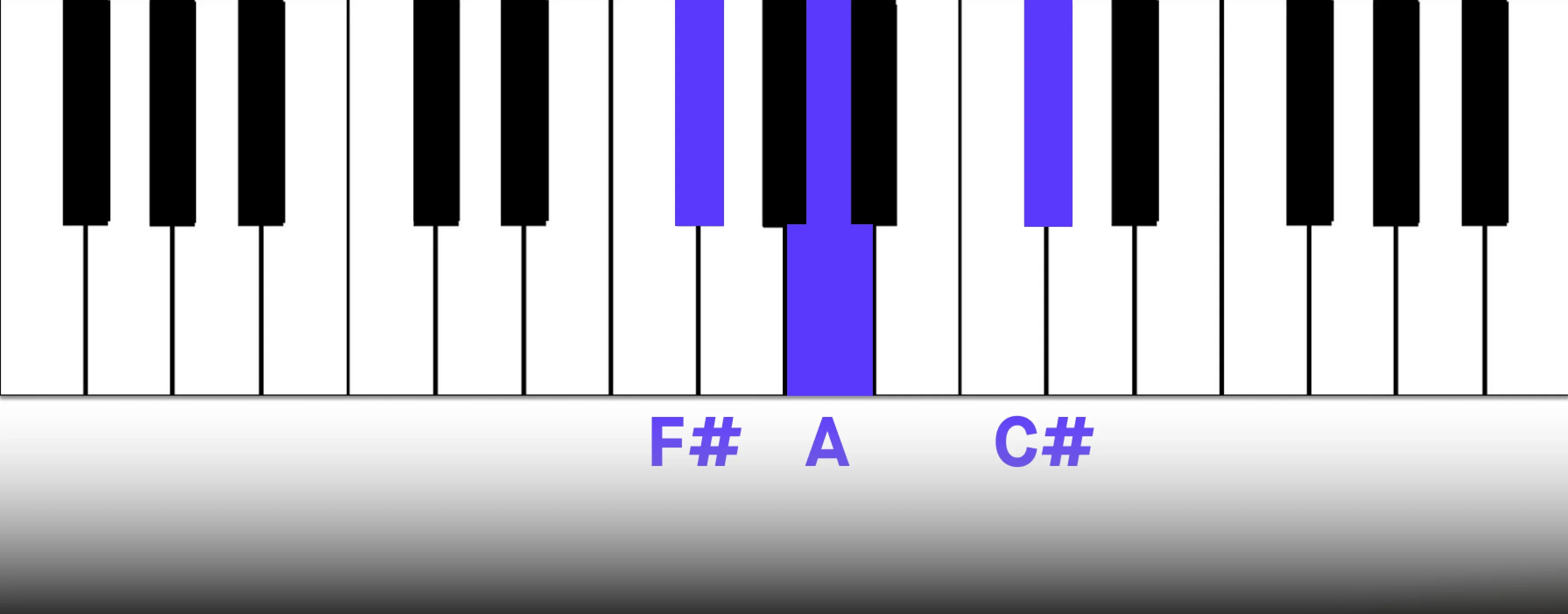

iii: F# Minor

The mediant chord can function as a tonic substitute. Sharing two notes with the tonic, it offers a similar sense of rest but with a distinct harmonic color.

Using tonic substitutes like the mediant can heighten the impact of the actual tonic chord. By delaying or avoiding direct resolution to the tonic, these substitutes create dynamic movement and harmonic interest.

Example: The bridge of Billy Joel's"Just The Way You Are"features a minor iii chord, creating a subtle shift in mood while maintaining familiarity.

IV: G Major

The subdominant chord plays an essential role in creating both harmonic contrast and anticipation. It provides a shift away from the tonic and sets up movement toward the dominant.

When followed by the V chord, it further intensifies the tension. This tension sets the stage for a powerful resolution back to the tonic.

The subdominant chord is crucial for establishing both harmonic contrast and anticipation. It often moves away from the tonic and leads into the dominant chord. When the subdominant is followed by the V chord, the tension of the progression increases.

Example: “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” by Queen opens on a D Major chord that is followed by a major IV chord in a D major key signature.

V: A Major

Alongside the tonic, the dominant chord is the most important chord in any key. It creates a sense of tension and movement, unlike other diatonic chords. This is because the third of the dominant chord is only a half step from the tonic. For that reason, the dominant chord creates a sense of urgency needing resolution.

The dominant is often perceeded and followed by the tonic. The latter is particularly common at the end of musical phrases. Beginning a musical phrase with a dominant chord generates energy and direction.

Example: The pre-chorus to Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb” modulates to a D major key and starts on an I-V-I-V progression. The chorus later starts on a dominant chord which gives the song energy.

“Up and Down the Bend” by Clarence and Clearwater uses a simple yet powerful I-V-I-V progression in the verse. The relationship between the I and the V is a cornerstone of traditional Western music theory.

vi: B Minor

The submediant chord is important for a few different reasons. For songs in a major key, the minor vi is often the primary minor color used. And, just like the mediant, it can be used as a tonic substitute that offers a sense of stability but in a contrasting color to the tonic.

Furthermore, the sixth scale degree is also the tonic of the relative minor key. Therefore the submediant chord can function as a bridge between two different tonal centers.

Example: Taylor Swift’s “Love Story” is a perfect example of using a traditional chord progression in D major to great effect. The chords in the chorus are I-V-vi-IV. Listen specifically to the harmonic quality the submediant offers.

vii°: C# Diminished

Diminished chords, containing the unstable and tense interval of a tritone (the devil's interval), often act as leading-tone chords in a major key. This means that the inherent dissonance of the chord creates a pull towards a resolution to the tonic chord, which is much more harmonically stable.

In pop and rock music, the diminished chord is commonly used as a passing chord or to increase tension before a strong resolution to the tonic. By holding the diminished chord for longer, the tension and anticipation are heightened, making the eventual resolution more impactful.

The 7th scale degree is commonly lowered a half-step in rock and pop music, changing the vii° chord to a major chord. This changes the Ionian mode to Mixolydian mode. In D Major, the result is a C Major chord instead of C#°.

A few examples of songs in D Major Mixolydian are “Lights” by Journey, “Royals” by Lorde, “Open Fire” by The Darkness, “I Want to be the Boy to Warm Your Mother's Heart” by The White Stripes, and “Taxman” by The Beatles.

These seven diatonic chords in D major are all you need to create great chord progressions. If you need help to get your next song started Musversal offers songwriting and production services as part of the Unlimited Subscription.

You can also check out the article “30 Unique Songwriting Promts to Craft Your Next Big Hit” to get you started.

Adding Depth and Complexity to Chords in D Major

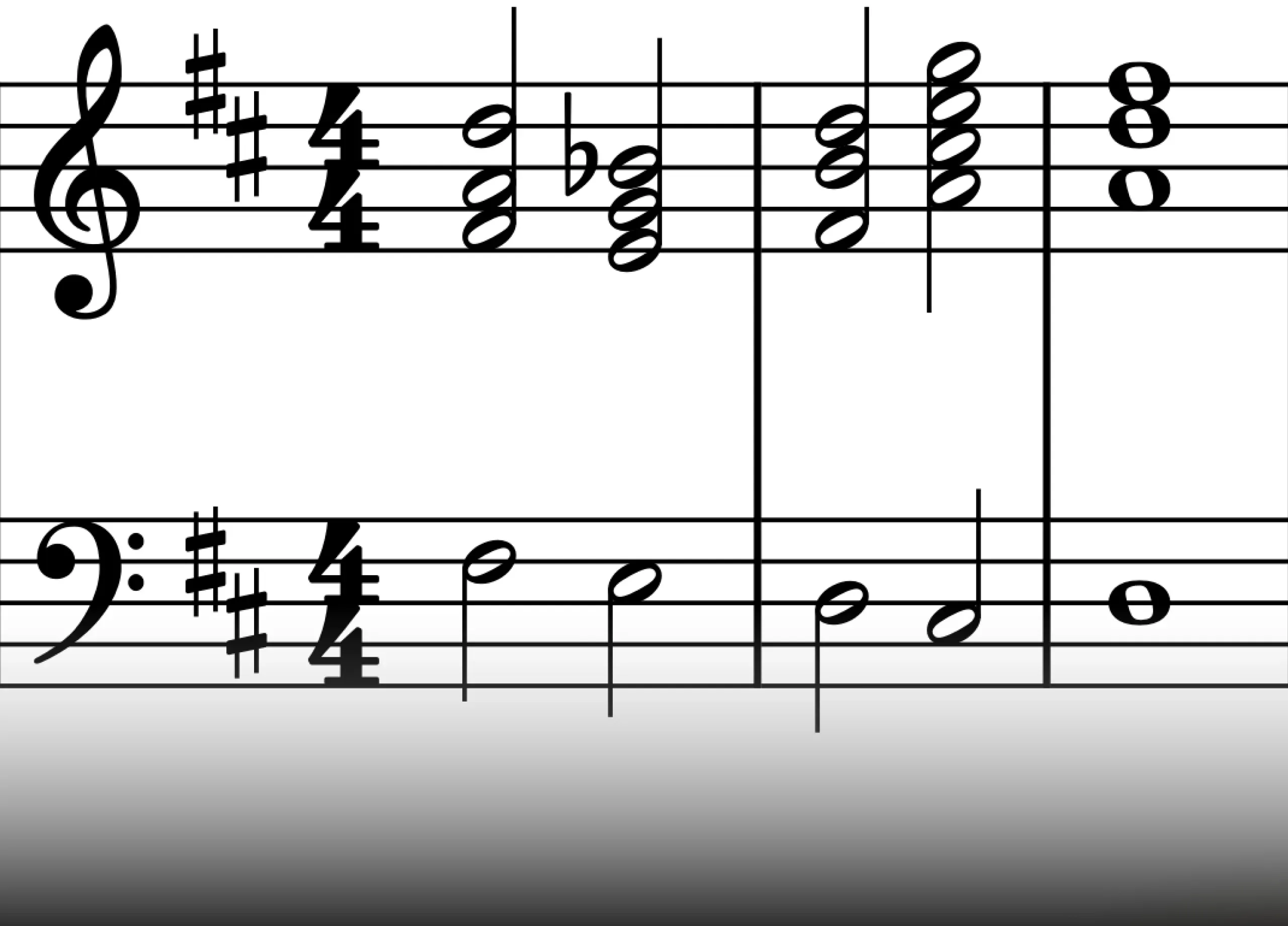

Seventh Chords in D Major

Seventh chords introduce tension and harmonic interest to the harmonic structure of a piece. They’re built by adding another third on a triad. By following the same pattern of the major scale, and only using diatonic notes, we’ll get four different kinds of seventh chords: Major 7, Minor 7, Dominant 7, and Half-diminished 7th chord.

- Major 7th Chords: These chords are formed by adding a major seventh interval to a major triad. They often convey a sense of brightness and resolution.

- Minor 7th Chords: These chords are created by adding a minor seventh interval to a minor triad. They tend to evoke a mellower and more melancholic mood.

- Dominant 7th Chords: These chords are built by adding a minor seventh interval to a major triad. They are frequently used to create tension and anticipation, leading the listener to expect a resolution to the tonic chord.

- Half-diminished 7th Chords: These chords are constructed by adding a diminished seventh interval to a diminished triad. They are commonly employed to generate a sense of instability and tension.

The inclusion of seventh chords in musical composition introduces a richer and more nuanced harmonic palette. The interplay between these different types of seventh chords can create a wide range of emotional effects and contribute to the overall musical narrative. For a more detailed guide on Seventh Chords in D Major, take a look at our article “A Comprehensive Tutorial on Creating Seventh Chords in D Major “.

Next, we’ll explore various diatonic and chromatic chords in D major, using both audio and notation for examples. If you're new to reading music, Music Matter’s Grade 1 Music Theory course on YouTube is a great place to start.

The Diminished Chord

Diminished chords are based on minor triad chords and are made up of a root note, minor third, and diminished fifth (a perfect fifth lowered by one-half step).

Here’s a quick example of replacing an E minor with an E-diminished chord.

Chords: D/F# - Edim - Bm/D - A7/C# - D

The unique, dissonant sound of diminished chords comes from the presence of the tritone, an interval spanning six half-steps. This inherent instability creates a natural tension that seeks resolution, making diminished chords a powerful tool for musical expression.

Diminished Chord’s Natural Occurrence Within Major Scales

Within any major scale, a naturally occurring diminished chord exists on the seventh scale degree. Notably, this vii° chord is intrinsically embedded within the Dominant 7th chord. The Dominant 7th chord itself contains a tritone, resulting in two notes that are a half-step away from the tonic. This close proximity to the tonic creates a strong pull toward resolution, explaining the Dominant 7th chord's inherent tension and its tendency to resolve to the tonic.

Functions of Diminished Chords

Diminished chords inject dissonance, suspense, and drama into music. They are a cornerstone of jazz music, where they are employed in various ways to create tension and release. While less common in contemporary pop and rock music, they still hold value in specific contexts.

For more information about jazz chords, check out the article “Jazz Chord Progressions”.

Primarily, diminished chords serve two main functions:

- Creating momentary tension: By introducing dissonance, they heighten anticipation and create a sense of unease, which can then be resolved by moving to a more stable chord.

- Connecting chords: They can act as a bridge between two chords, smoothing the transition. For instance, to move from the submediant to the tonic, a diminished chord built on C# can be used as an intermediary step

Adding Variety and Interest to Chord Progressions

Beyond their functional roles, diminished chords can be used creatively to add variety and interest to harmonic progressions. By transforming any chord into a diminished chord, musicians can introduce unexpected twists and turns, keeping the listener engaged.

Diminished chords, with their characteristic dissonance and inherent tension, play a vital role in musical composition. Their ability to create drama, connect chords, and add variety makes them an invaluable tool for musicians across various genres. By understanding their structure and function, musicians can harness their power to craft compelling and expressive musical experiences.

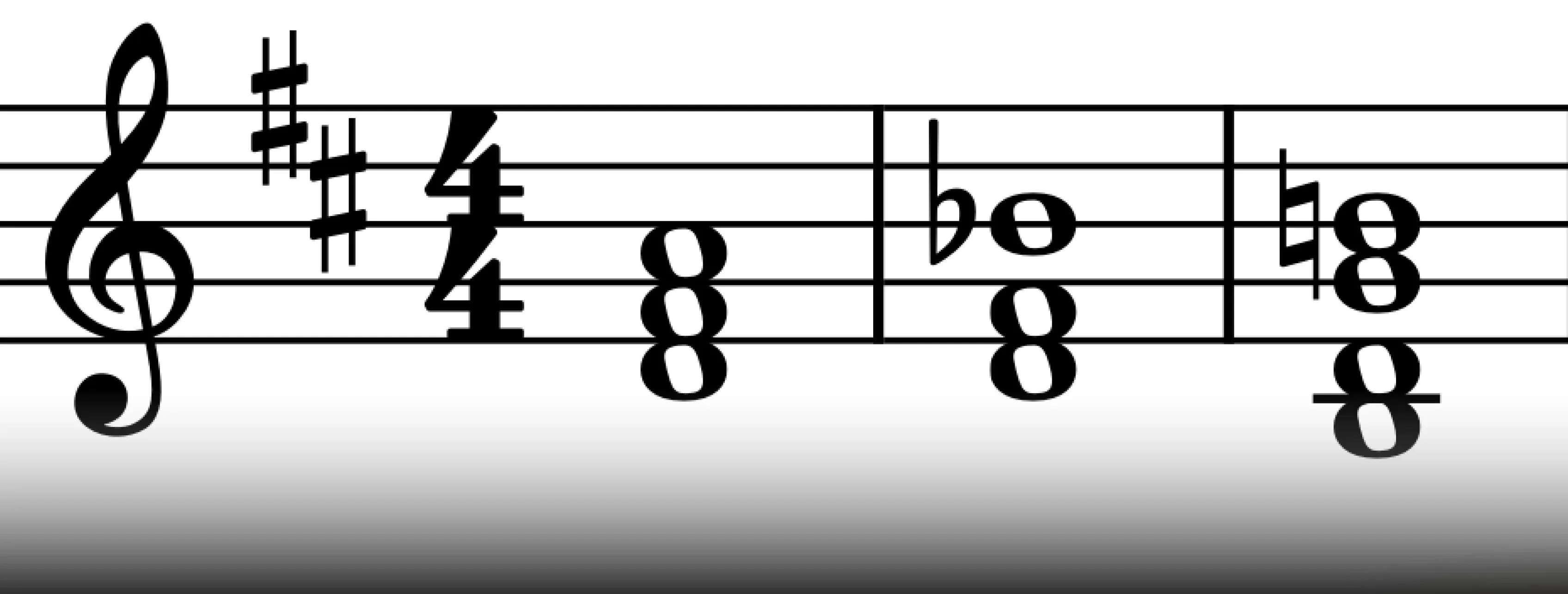

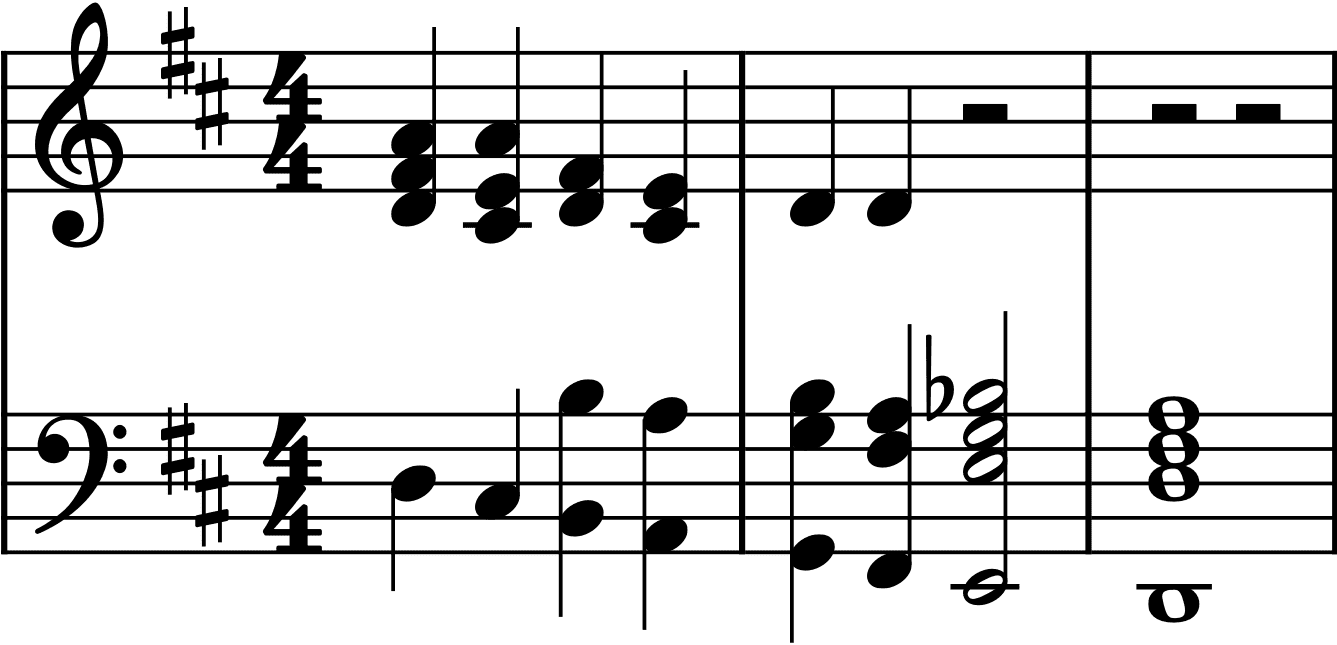

The Augmented Chord

An augmented chord has a root note followed by two major thirds, creating an open sound yet dissonant sound. Because there are no naturally occurring augmented chords within the D major scale, you'll need to incorporate chromatic notes to use them.

The use of augmented chords and chromatic notes can add complexity, tension, and a sense of movement to a musical composition. They can be used to create unexpected harmonic shifts, modulate to different keys, or simply add color and variety to the overall sound. While they might not be as common as major or minor chords, augmented chords play a valuable role in the world of music theory and composition, offering a unique sonic palette for musicians to explore.

Here’s a piano example of Green Day’s “Last Night on Earth” transposed to D Major.

Chords: D - Daug - D6 - D7 - G - Gm - D

The raised fifth creates a sense of tension and ambiguity, making the augmented chord sound unresolved and yearning for resolution. This combination of intervals distinguishes the augmented chord from both major and minor chords, as it lacks the perfect fifth found in those triads.

Uses and Functions

Two of the most common uses of augmented chords are to place them on the dominant scale position resolving to the tonic, and on the tonic resolving to the 4th scale degree.

Chords: Aaug - D

Chords: D+ - G

Despite their instability, augmented chords have several uses in music:

- Chromatic and stepwise motion: Augmented chords can create smooth transitions between chords by moving chromatically or in step-wise motion. The raised fifth can lead smoothly to notes in adjacent chords.

- Tension and resolution: The inherent tension of the augmented chord makes it a powerful tool for building tension and anticipation in music. This tension can be resolved by moving to a more stable chord.

- Modulation: The ambiguity of the augmented chord can be leveraged to modulate to a different key. The raised fifth can act as a pivot point, leading to a new tonal center.

Suspended chords

Sus Chords: Beyond Major and Minor

Unlike major and minor chords, which possess a distinct tonal quality due to the presence of a major or minor third, sus chords introduce ambiguity by altering the third. This alteration involves either lowering the third to the second scale degree, resulting in a sus2 chord, or raising it to the fourth scale degree, creating a sus4 chord.

The seventh scale degree's diminished chord cannot become a suspended chord. However, a workaround exists by using the Mixolydian mode. Lowering the seventh scale degree creates a C major chord, which can then change to sus2 or sus4.

The Ambiguous Sound

The absence of a clear major or minor third in sus chords lends them a sense of openness and unresolved tension. This ambiguity can be used to create a variety of moods in music, from ethereal and dreamy to suspenseful and anticipatory.

The suspended chord doesn't provide a clear resolution, leaving the listener in a state of anticipation. This unresolved quality can be used to create a wide range of emotions and atmospheres in music.

Uses and Functions

The unique sound qualities of sus chords make them versatile tools for musicians and composers. They are frequently used in a variety of musical contexts, including:

- Creating a sense of suspension: As their name suggests, sus chords can generate a feeling of suspension or unresolved tension. This can be particularly effective in transitional passages or moments of anticipation.

- Adding color and texture: Sus chords can introduce subtle variations and nuances to chord progressions, preventing them from becoming predictable or monotonous.

- Evoking specific moods: The ambiguous nature of sus chords can evoke a range of emotions and atmospheres in your music. The open sound creates a feeling of floating or weightlessness

The sus4 chord on the 5th scale degree can be especially useful to prolong the tension that naturally occurs on the dominant position. The interval of Vsus4-V-I is a great way to complete musical phrases.

Chords: D - Asus4 - A - D

Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” sus4 chords to achieve that sense of openness and ambiguity in the intro.

Chords: D - Dsus4 - D - Asus4

Suspended chords provide a particular color and complexity to a chord progression. The specific emotional effect of a sus chord will depend on the musical context, including the surrounding chords, instrumentation, and tempo.

The sus2 chord, while offering some tension, its desire to resolve less compared to the sus4 chord. Instead, the sus2 is often used on its own in chord progressions.

Chords: D - Dsus2 - Dsus4 - D - Asus4 - A - Bm - Asus2 - D

Suspended chords are a valuable asset in any musician's toolkit. By understanding their structure, sonic characteristics, and musical applications, you can unlock a world of creative possibilities in your own music.

Power Chords

Power chords are fundamental to rock music. They’re known for their raw, impactful sound and adaptability. They’re constructed using only two notes: the root and fifth which means, just like suspended chords, they're neither major nor minor.

Their simplicity allows them to fit in seamlessly with various melodies and harmonies, making them ideal for high-energy genres, which is why you’ll always hear them in rock chord progressions.

A key reason for their popularity in rock is their ability to deliver a full, aggressive sound, even with heavy distortion. The lack of the third, which defines the chord quality, prevents harmonic clashes and unwanted dissonance.

Distorted guitar is a cornerstone of rock music, and power chords play a crucial role in achieving that particular sound. By omitting the third (the note that defines a chord as major or minor), power chords avoid muddiness, maintaining clarity even with heavy distortion and high gain. This streamlined structure allows the raw power of the root and fifth to shine through.

Finally, power chords are remarkably easy to play, particularly on guitar. The consistent hand position for each chord, combined with simple movement up and down the fretboard, makes them accessible and efficient for creating powerful riffs and progressions.

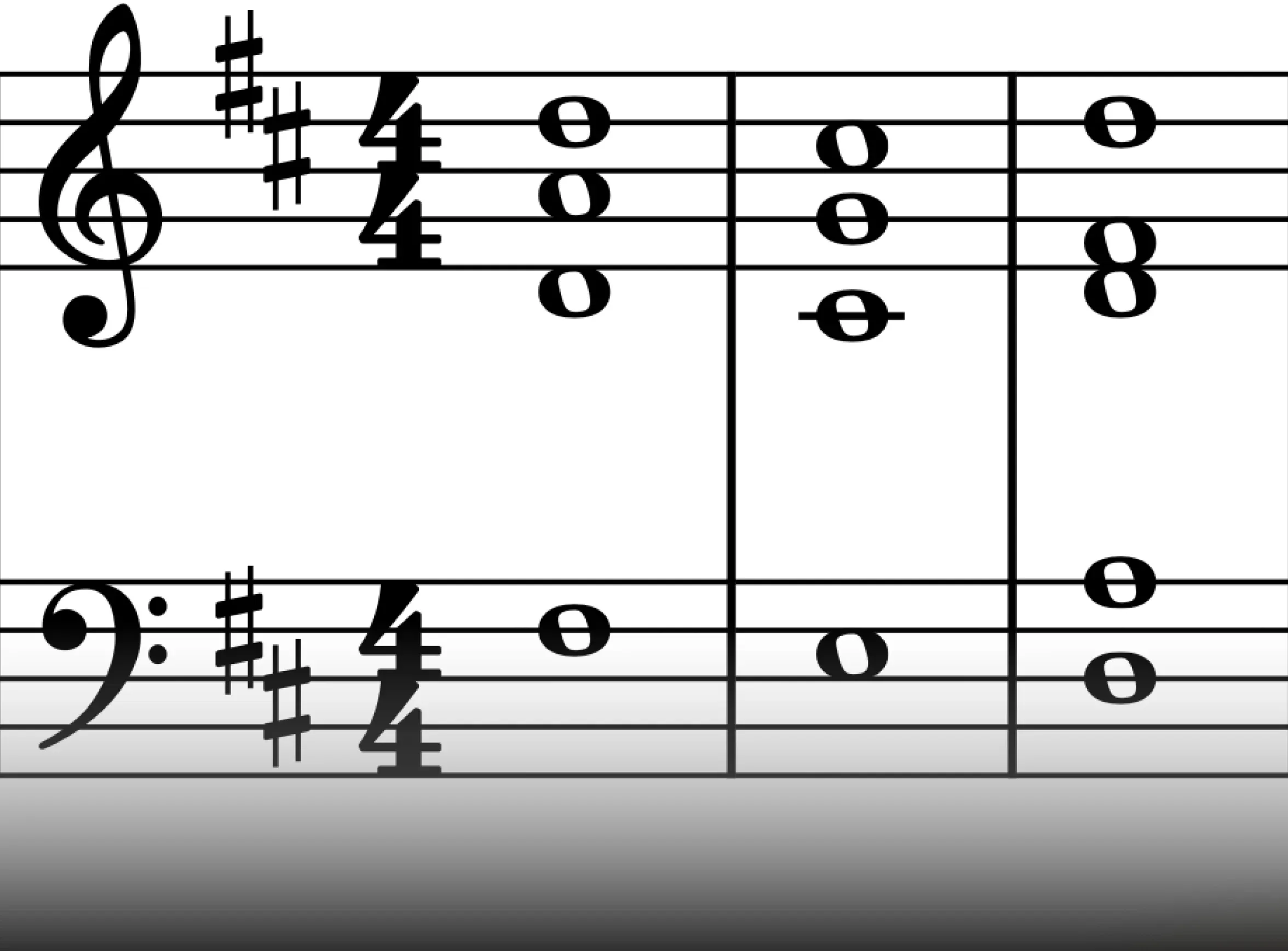

Chord Inversions

A chord inversion is when you replace the tonic as the lowest note of the chord with any of the other chord notes. They offer a way to add variety and depth to your chord voicings.

A 1st inversion occurs when the third of the chord is the lowest note; a 2nd inversion is when the fifth is the lowest; and in seventh chords, a 3rd inversion means you put the 7th note at the lowest note of the chord.

These inversions offer a variety of musical possibilities and can significantly impact the sound and feel of a chord progression.

Next, we’ll look at a few different reasons to go beyond triads and use chord inversions.

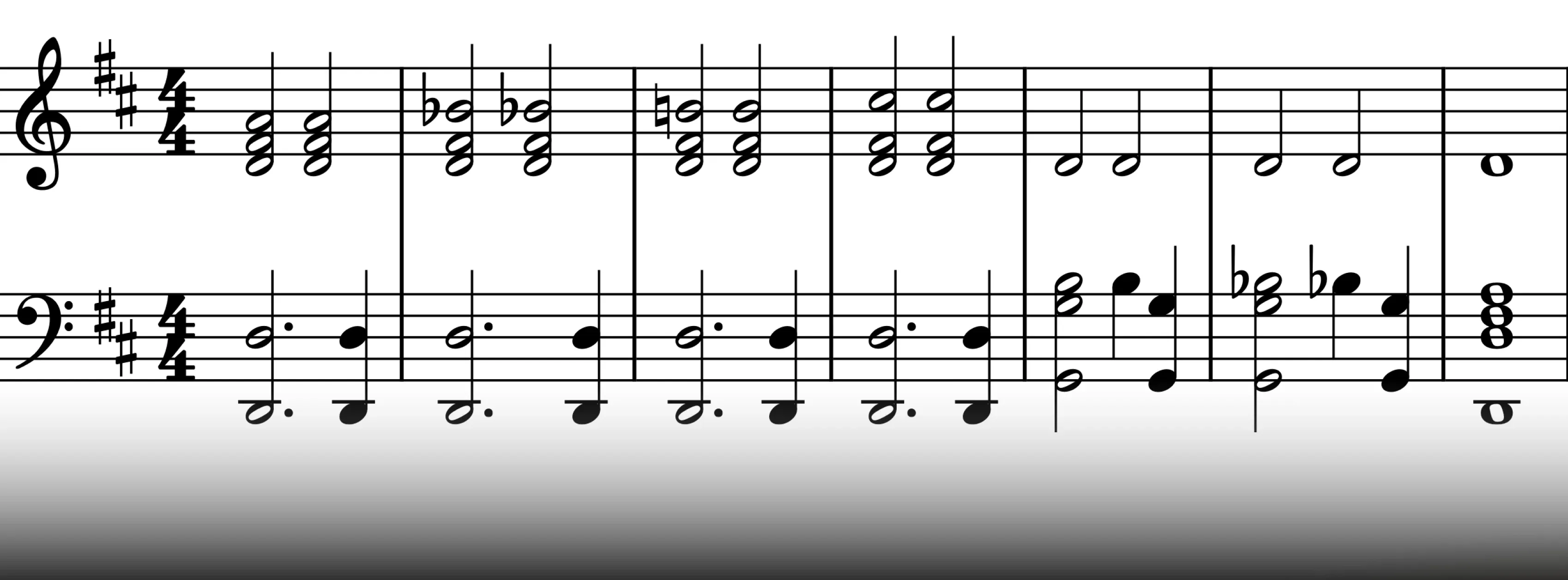

Smooth Voice Leading

The overall sound of the chord can be affected by rearranging the notes within it, even though the lowest note determines the type of inversion being played.

Chord inversions are frequently used to create smoother voices leading between chords. This means that the individual voices within a chord progression move in a more stepwise and connected manner when inversions are used. By minimizing large leaps between notes, inversions contribute to a more fluid and pleasing musical texture.

Here's an example of using inversions in a chord progression to create smoother transitions between notes:

Chords: D - A - Bm - A - D

Voice leading is particularly important when arranging for multiple instruments. Smooth voice leading helps maintain clarity and balance.

Inverting chords can also allow you to create stepwise ascending or descending basslines for movement or build up tension.

Here is an example of using inversions to create a descending bassline in D major. This chord progression also contains the chromatic chord E°.

Chords: D - A - B - A - G - D - Edim - D

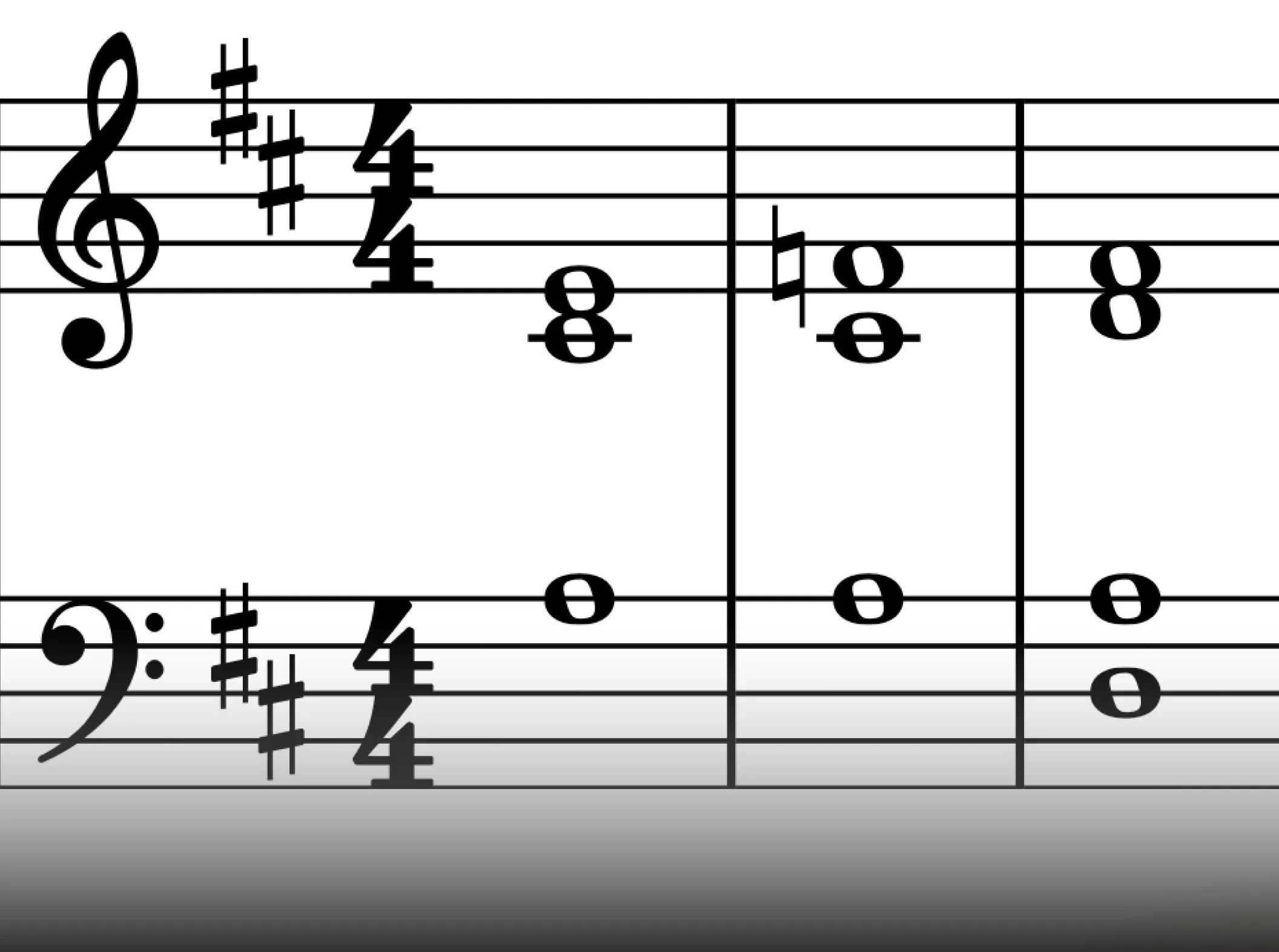

Stability and Sound

Chord inversions can subtly alter the stability and sound of a chord, allowing for greater expressiveness and variety without creating dissonance. For instance, a root position chord often sounds more grounded and stable, while an inverted chord can create a sense of movement or tension (at least less stability).

Below is an example of a progression with a D Major in 1st inversion, A major in 2nd inversion, and finally a D major in the root position. Notice the subtle difference in stability between the first two chords and the final chord.

Chords: D (1st Inversion) - A (2nd Inversion) - D

Inversions are also particularly useful for starting or ending musical phrases on the tonic chord in a less resolute or conclusive way. This adds nuance and sophistication to the music, preventing it from sounding monotonous or predictable.

This flexibility allows for a wide range of voicings and textures within a chord progression. For instance, you can start a song in the tonic and then alter the voicings instead of playing a new chord and instantly altering the character of the chord.

Variety and Color

Using inversions adds variety and color to music. They allow composers and musicians to explore different voicings and textures, creating a richer and more dynamic listening experience. Inversions can also help to highlight specific notes or melodies within a chord progression, drawing the listener's attention to important musical ideas.

The main riff in Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud” uses two consecutive D Major chords as the first two chords in the phrase. While both chords are D Major, Sheeran uses different inversions to create subtle variations and give each chord a unique character.

Learn How to Recognize Intervals

When composing music that utilizes both triads and inversions, a strong understanding of each interval's unique sound is crucial. By training your ears to quickly identify intervals, you can compose music more efficiently and purposefully, as you eliminate the need to experiment with various chord combinations.

The most effective way to identify intervals is by associating each one with a well-known song. Our “Ear Training” article provides a selection of songs for both ascending and descending intervals to aid in practicing interval recognition.

What’s next?

Explore our article “A Comprehensive Guide in D Major Chord Progressions” and learn how to write unique and interesting progressions for your next song and learn how D Major chords are used in popular songs.

Dive deeper into the world of D Major with our detailed guide and learn how you craft unique and compelling chord progressions that will breathe life into your compositions.

In the article we’re exploring how you write captivating chord progression with movement, tension, and release; as well as looking at cadences to complete your musical phrases with intention.

By analyzing famous songs in D Major we can see how both diatonic and chromatic chords are put into action.

We’re looking at how you can spice up your compositions using chord substitutions, secondary dominants, etc to create unexpected harmonic shifts that will keep the listener engaged. The article also briefly touches on key changes to make the music come alive.

Musiversal: For Musicians, by Musicians

Musiversal is a remote recording studio allowing subscribers to access 100+ individual session musicians and audio engineers. With our Unlimited Subscription, you have unlimited recording sessions just one click away, you have unlimited recording sessions just one click away.

Find the instrument or artists you need for your song (drums, cello, guitar, strings, piano, winds, bass, beat makers, producers, etc) and simply pick a time on their schedule that suits you. You can join your recording session live via link and hear your music come alive and collaborate with the musician in real-time.

If you don’t yet have a completed song to record, you can use our songwriting services, production advice sessions or simply schedule a meet and greet with an artist you wish to work with to pick their brain or ask about the recording process. Our engineers offer mixing and mastering sessions to make your music shine!

We also offer marketing sessions to make sure you’re able to get your music heard by as many people as possible.

For more tips and advice on music theory, songwriting & creativity, music, production, gear, marketing & distribution, keep an eye out for the Musiversal Blog. We updated it weekly. Subscribe to our newsletter and receive notifications on our exclusive Musiversal discounts, gain insights from inspiring session highlights, get helpful marketing advice, and much more!

Join The Musiverse: Your free space to connect, create, and compete.

Collaborate with global creators, level up in live workshops, and win exclusive prizes. Join the community today!

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist