Learn the Chords in A Minor: A Music Theory Resource

Explore the chords in A Minor and common chord progressions in A Minor. Written for music producers seeking to enhance their melodic and harmonic skills.

Introduction

Understanding how different chords, intervals and chord progressions sound in different keys is an important part of writing music with clear intention. Knowing what’s available to you in any given key signature will help you take your music to a new level melodically and harmonically.

When you unlock the ability to create more interesting harmonies, apply key changes, use parallel and borrowed chords, and so on, you can take your music to a whole new level.

In this article we’ll look at chords in A minor, the harmonic function of each chord, cadences to complete music phrases and common chord progressions in A minor. Lastly, we’ll also look at how you can add complexity and interest to chord progressions by using parallel chords and secondary dominants.

The Basics of A Minor

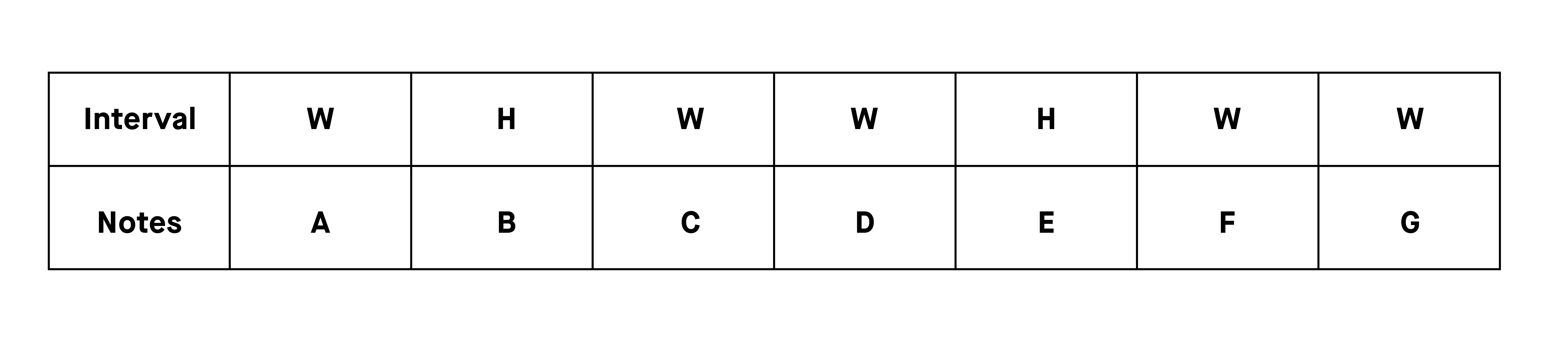

There are three main types of minor scales: natural, harmonic, and melodic. The pattern of whole steps (W) and half steps (H) is what makes each scale unique. The A natural minor scale consists of the following notes:

Unless otherwise specified, "minor key" typically refers to the natural minor scale, which is what we’ll explore here.

Each note in a scale has a specific position known as a scale degree. These scale degrees indicate its relationship to the tonic (root) of the key.

- A - Tonic

- B - Supertonic

- C - Mediant

- D - Subdominant

- E - Dominant

- F - Submediant

- G - Subtonic/Leading Tone

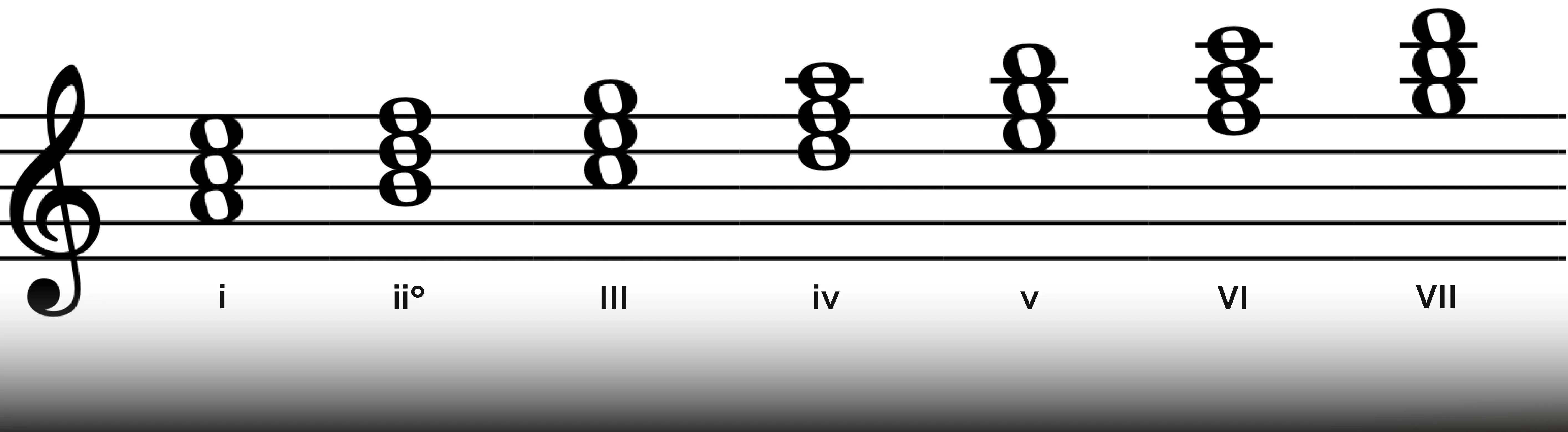

The chords are built on these seven scale degrees which gives each chord a specific function in the given key signature. Harmonic chord function can simply be described as the level of tension or resolution the chord has in relation to the tonic.

Furthermore, roman numerals are used to indicate both the chord's harmonic function in the given key signature and its quality. Uppercase numerals means major chord, and lowercase means it’s minor. The number itself represents the scale degree.

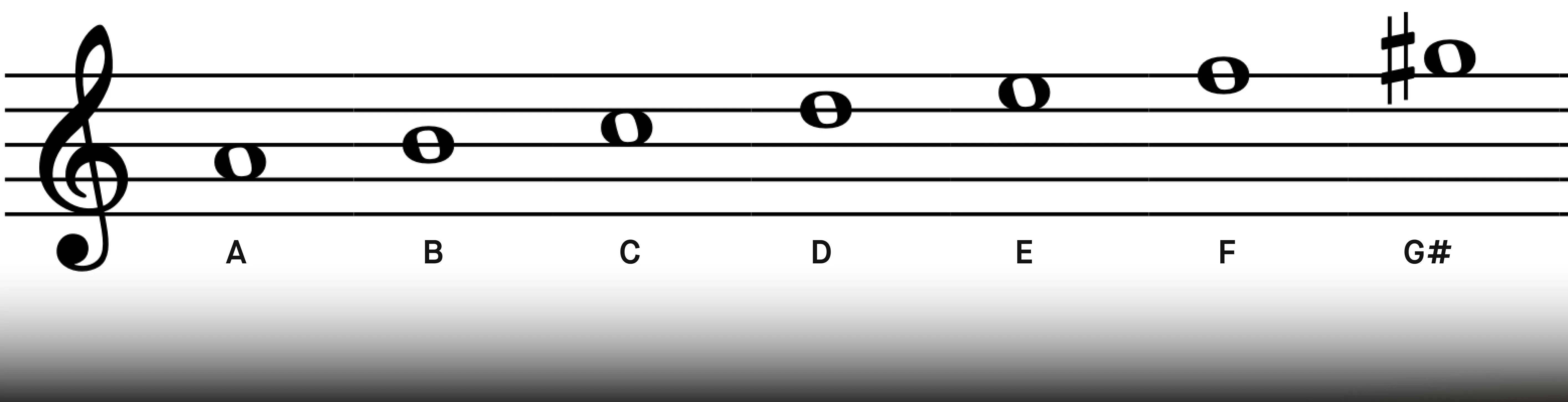

Diatonic notes are the notes that naturally occur within the scale. Chromatic notes are not part of the scale but they can add specific harmonic tonalities and qualities to the music.

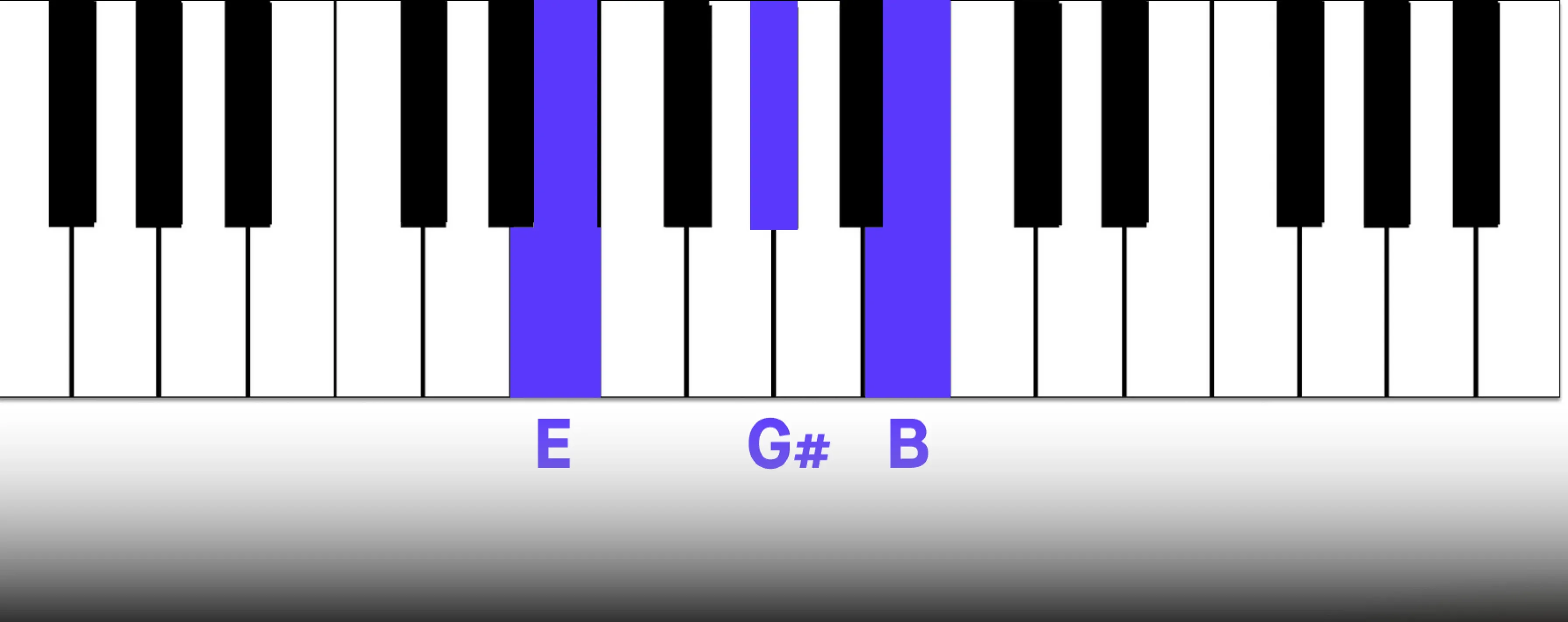

One common chromatic alteration in minor keys is raising the leading tone (the seventh scale degree) to a sharp. In A minor, this means raising G to G♯. This creates a stronger sense of resolution to the tonic and is often used in the dominant chord (the chord built on the fifth scale degree).

The altered notes are called Accidentals and are marked as sharps (♯), flats (♭) or natural (♮) to indicate that it’s gone back to its original pitch.

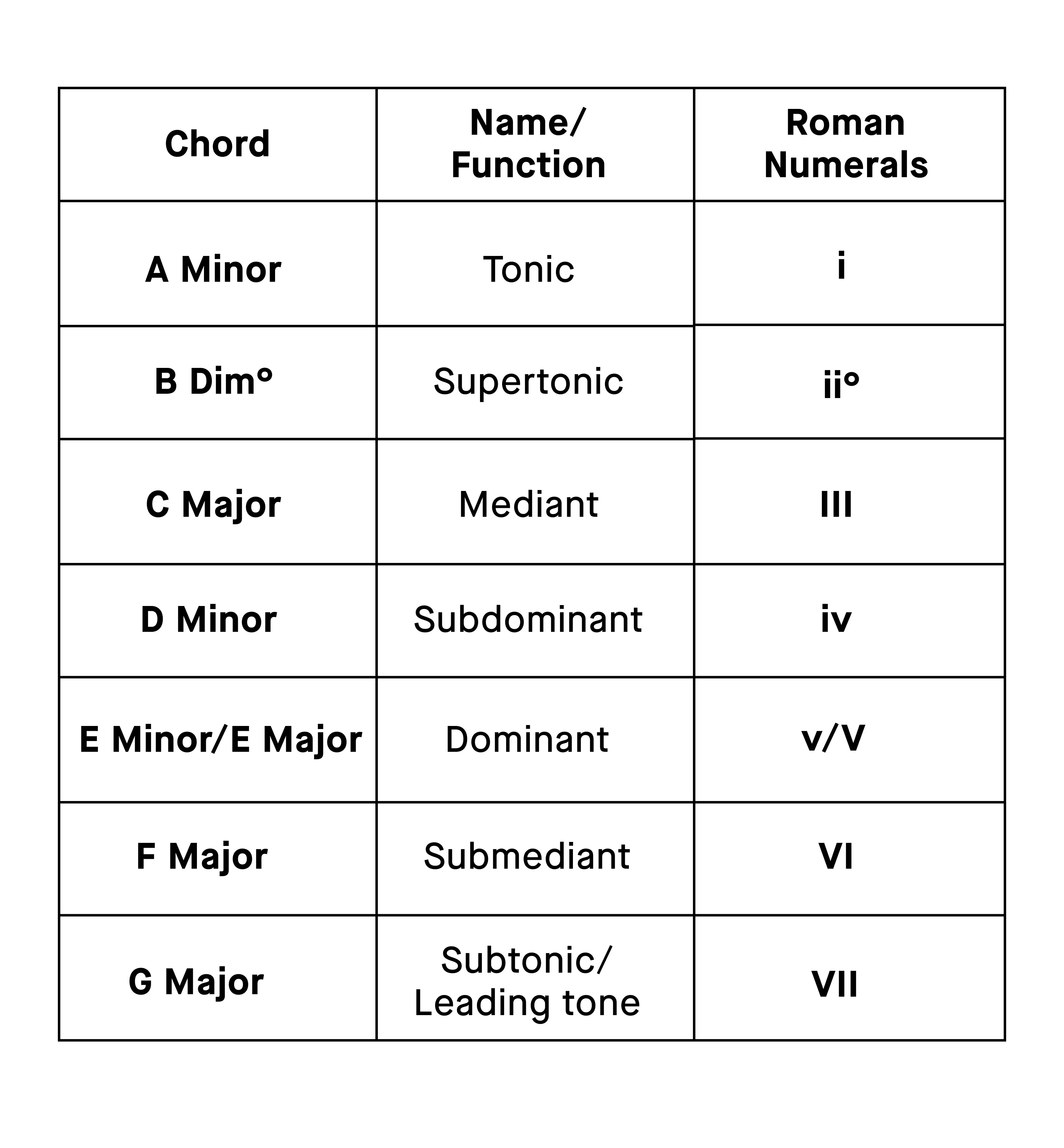

Chords in A Minor

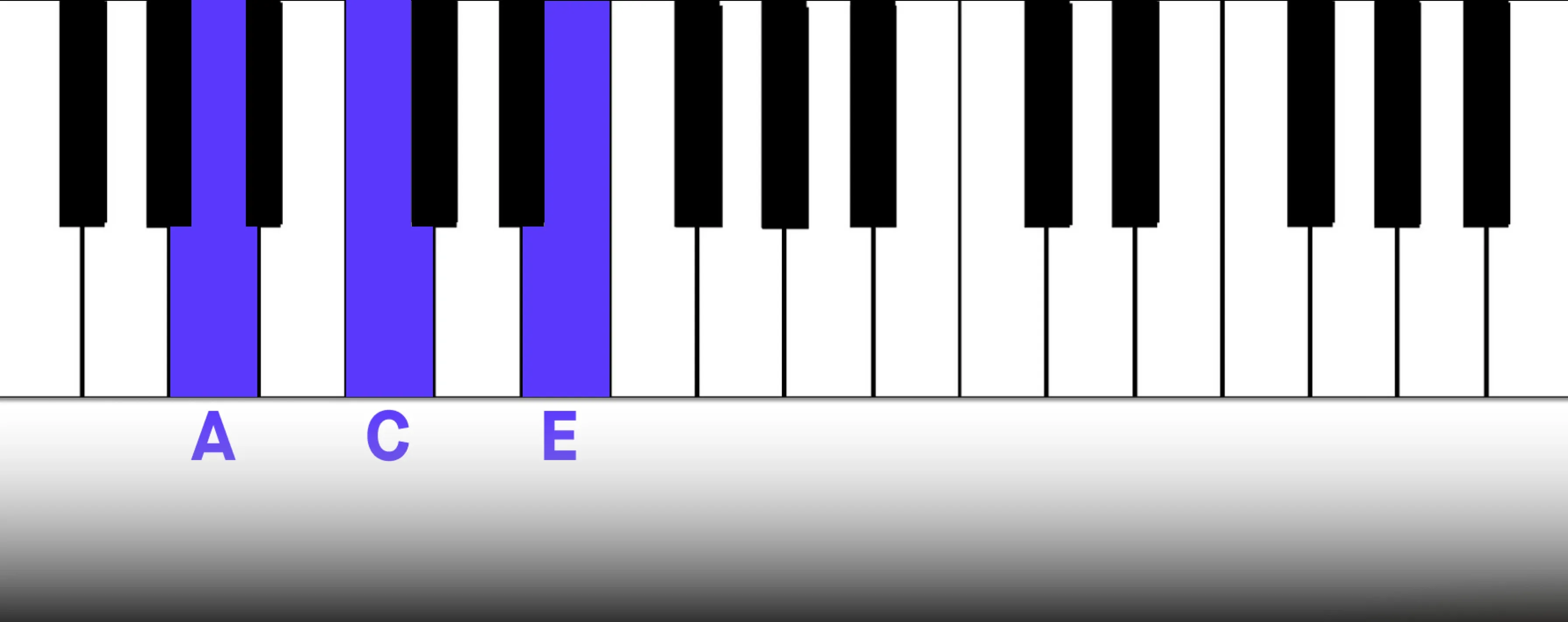

i: A Minor

This is the foundation of the key signature. It provides strong resolution and stability. Starting with, or returning to the tonic feels natural, and conclusive. It’s like the chord progression is arriving back home.

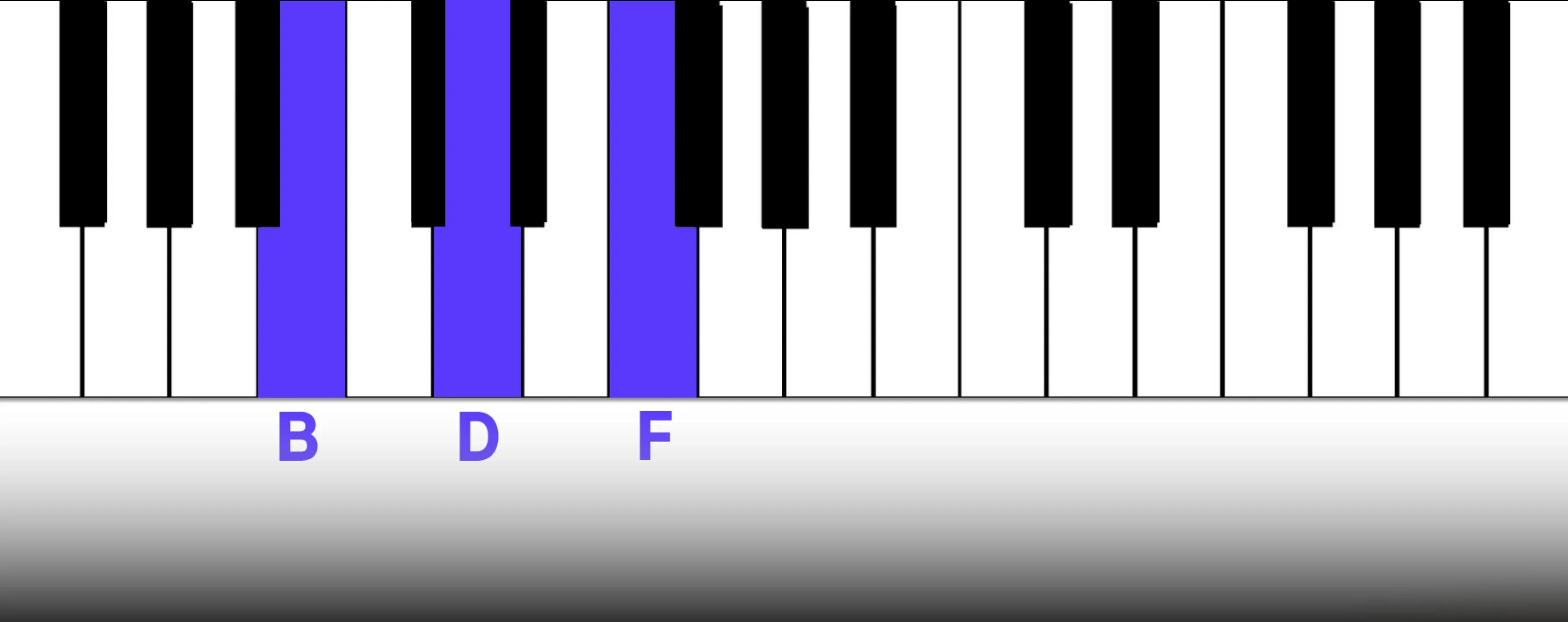

ii°: B Diminished

Due to the dissonance of this chord, it’s often used as a passing chord, meaning you use it for a smoother transition from one chord to the next.

Diminished chords are a staple of jazz music, but less frequently used in different styles of pop or rock music.

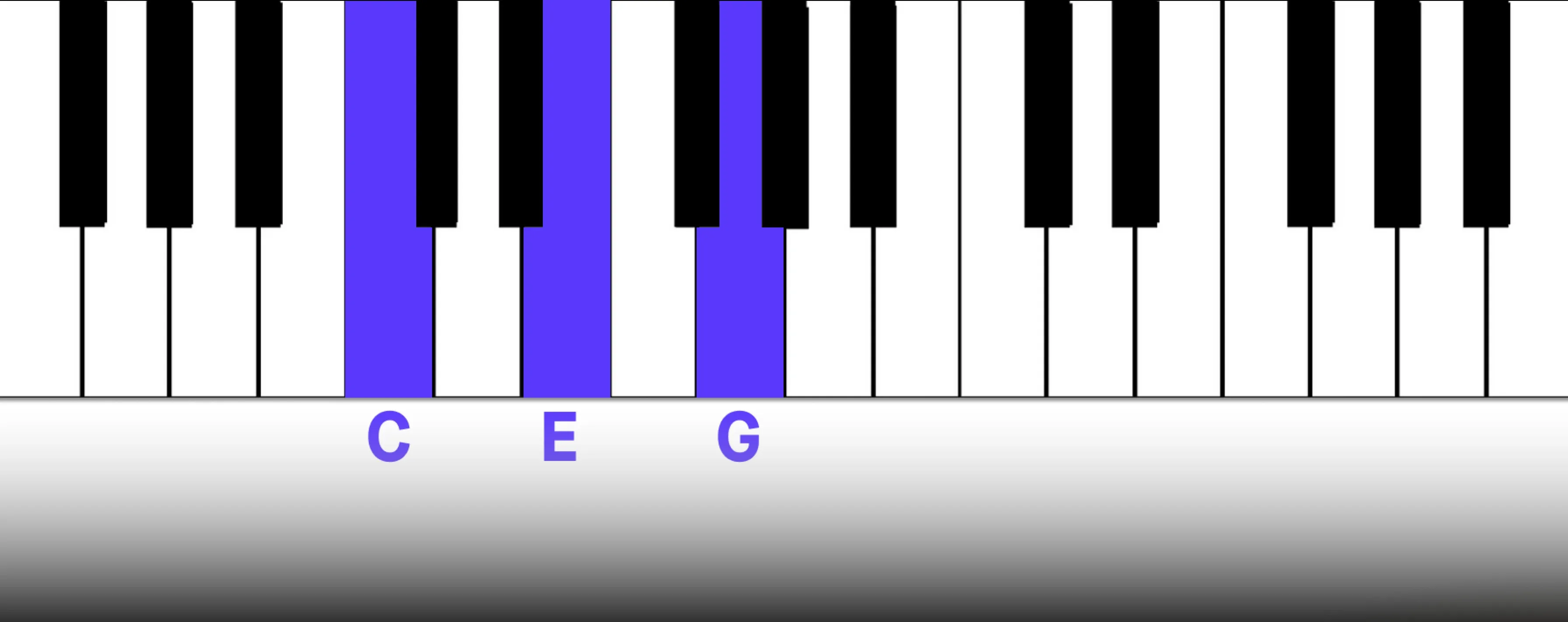

III: C Major

The mediant adds brightness to a chord progression. It shares two notes with the tonic, which makes the interval i - III particularly smooth. The mediant, or third scale degree, is also the tonic of the Major relative key signature (more on this later).

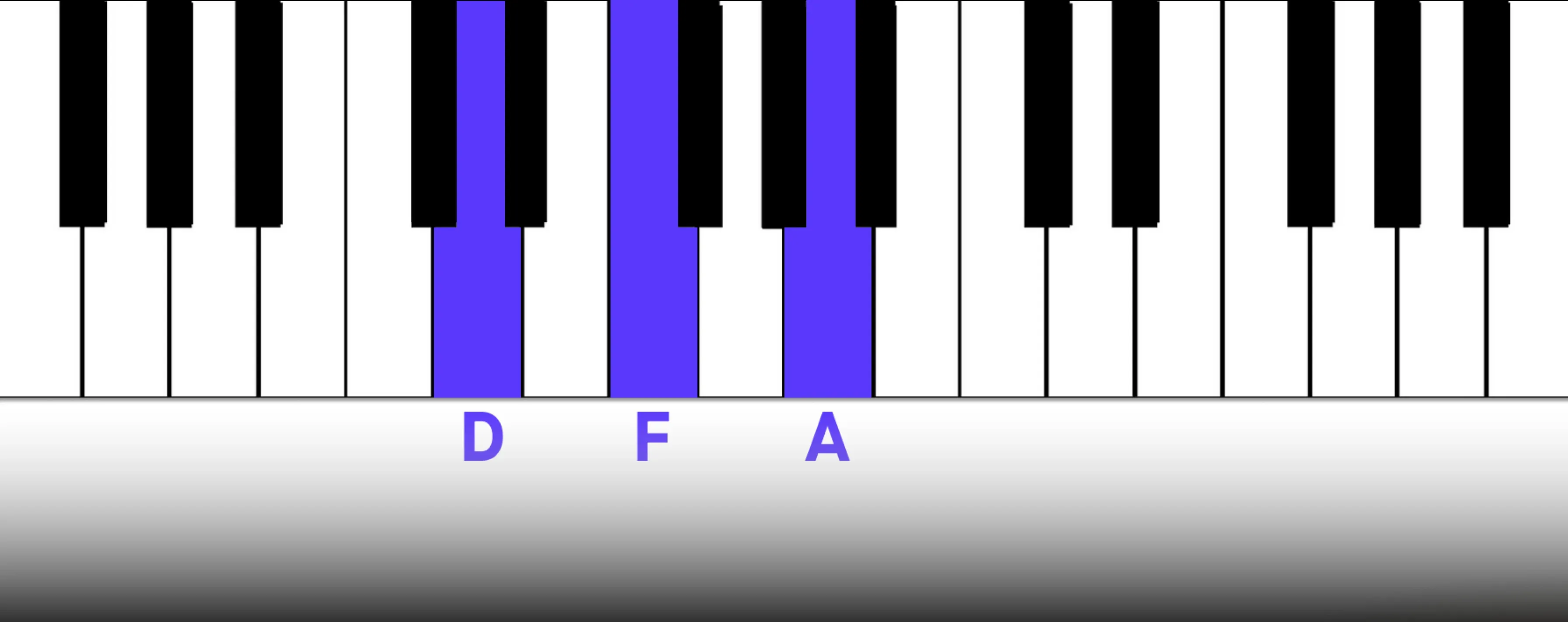

iv: D Minor

It has a strong sense of anticipation and adds a somewhat contrasting feeling to the tonic. The subdominant chord offers several great options in a chord progression. It can move to the tonic for resolution or to the dominant for increased tension. It frequently moves to the VI chord, too, some stability in a major tonality.

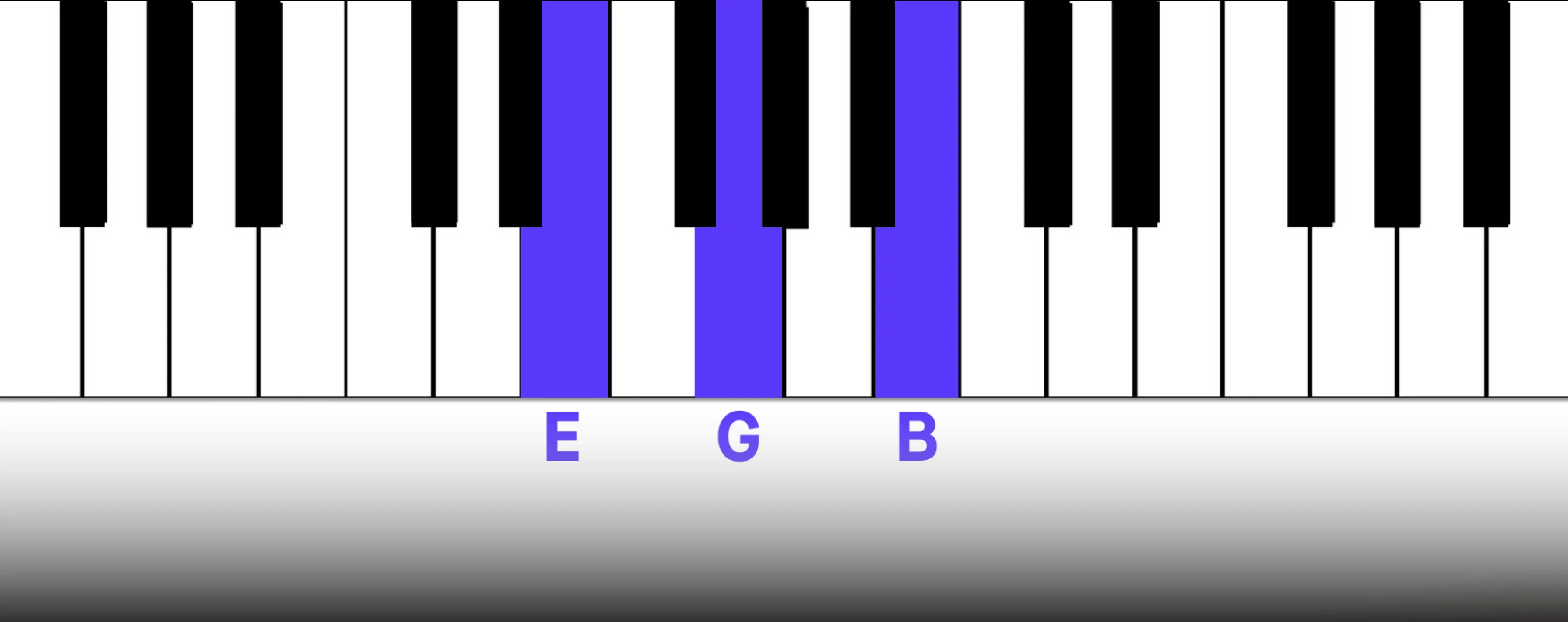

v/V: E Minor /E Major

The dominant is the most unstable chord. It creates tension and has a desire for resolution, most often to the tonic. The Major V has a stronger sense of resolution and is therefore more commonly used.

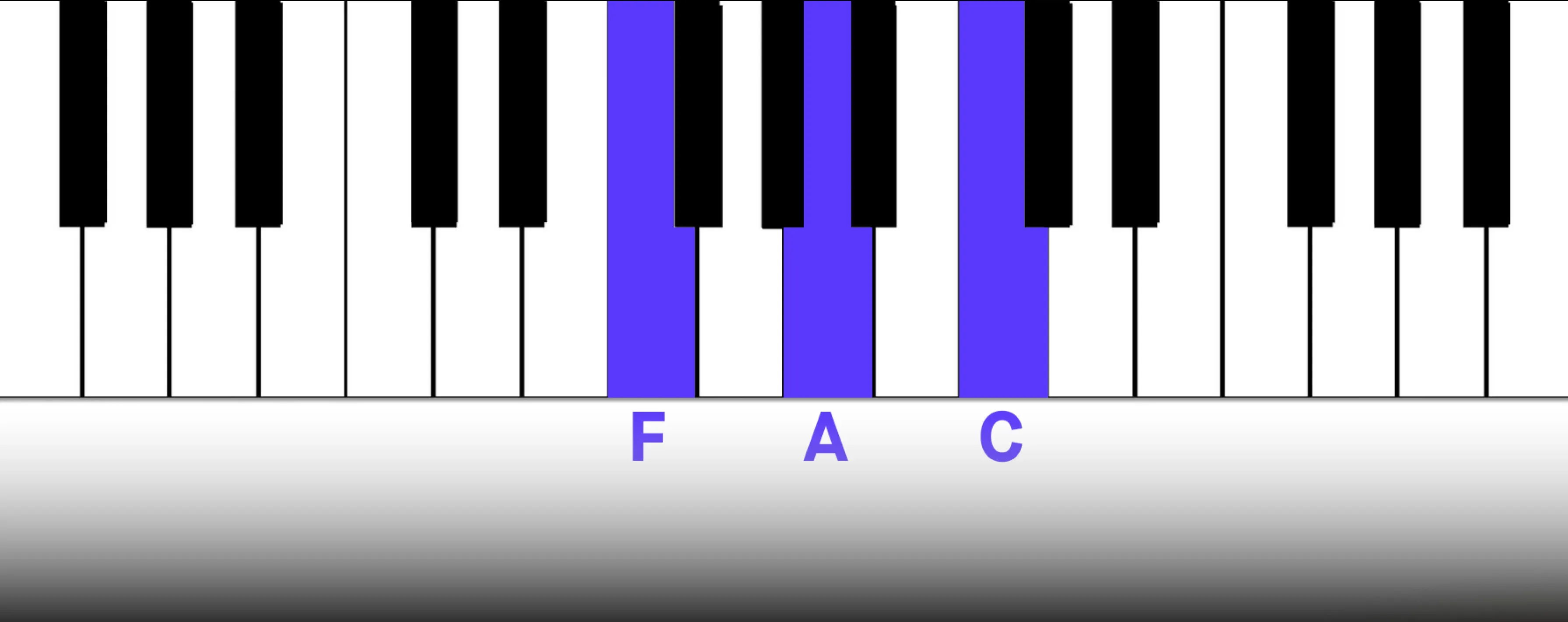

VI: F Major

Its bright, major quality offers a sense of optimism and uplift in contrast to the darker, minor tonality of the tonic chord. The interval i - VI is commonly used due to the juxtaposition of minor and major chords. Because it shares two notes with the tonic it still provides some stability.

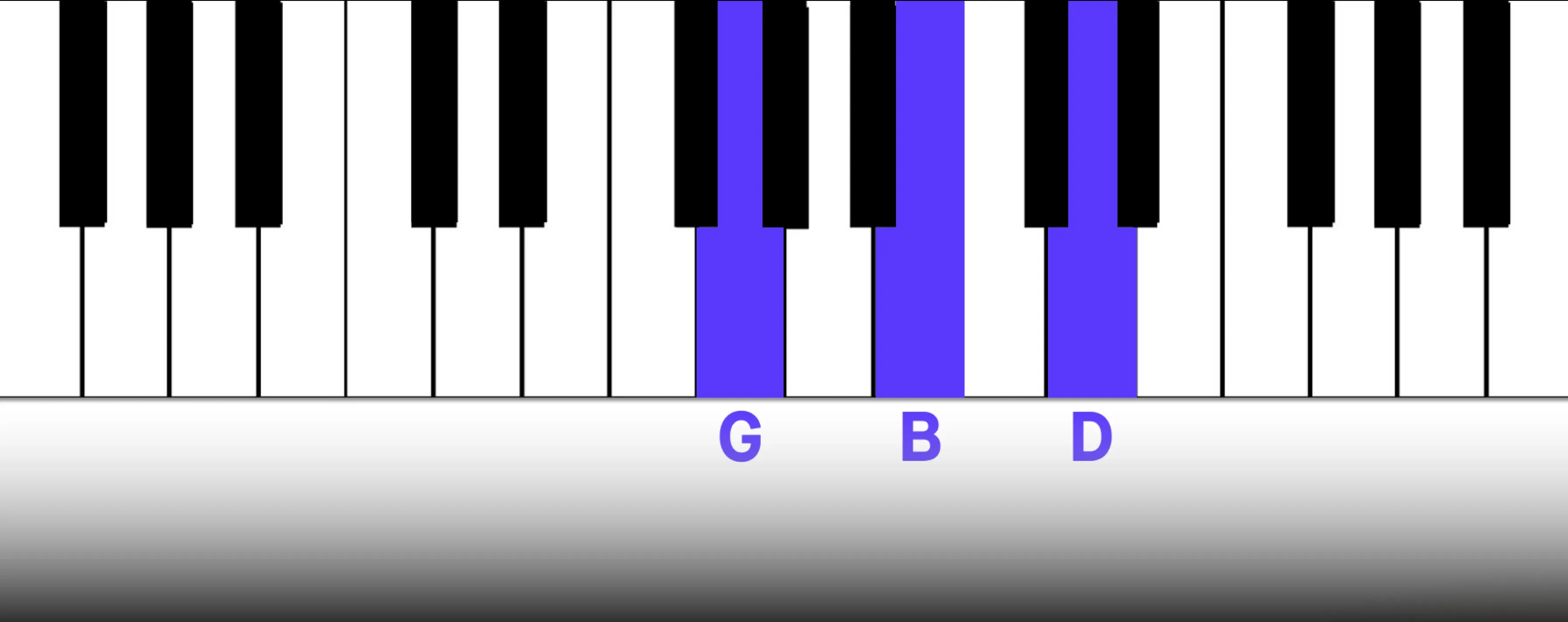

VII: G Major

G major has a strong pull to resolve to tonic. In a minor key, Major chords can have an inherently dissonant quality to them. This chord in particular has a strong need for resolution to the tonic. The interval VII - i comes very naturally and is commonly used.

Primary and Secondary Chords in A minor

The chords in A minor are divided into two categories: Primary chords and secondary chords. Primary chords provide the fundamental harmony in any chord progression, and secondary chords add a more specific harmonic flavor to a song.

- The primary chords are i, iv and v/V

- The secondary chords are: ii°, III, VI and VII

Understanding Chord Relationships and Intervals

To deepen your understanding of chord intervals and their sounds, experiment with various chord combinations. Start with the tonic chord and explore the intervals to all diatonic chords, one by one.

- Practice chord progressions: Move from the tonic to other chords in the scale to understand how each combination sounds.

- Experiment with inversions: Play each chord in different inversions to change the sound.

By practicing these exercises, you'll expand your chordal and interval vocabulary. This will allow you to write more interesting and varied chord progressions.

To create harmonious melodies and well-structured chord progressions, it's essential to have a solid grasp of scale patterns and intervals. Knowing where each of the half and whole steps are in A natural minor will help you create a smoother voice leading. This minimizes large gaps between notes as you move from one chord to the next.

Cadences in A minor Chord Progressions

A cadence is an interval of chords that completes a musical phrase. Different cadences can convey different sensations in your music and are for different purposes throughout a song. Some cadences have a stronger sense of resolution than others.

Think of cadences as musical punctuations. Sometimes you want to end with a statement, or an exclamation point; other times you want to be more ambiguous or end on a question mark.

Strategically utilizing different styles of cadences can bring your music to life. You can strengthen certain passages in your music by saving the most powerful cadences for these key moments. This will heighten the overall emotional impact of your music.

Here we’ll look at a few of the most common cadences in A minor.

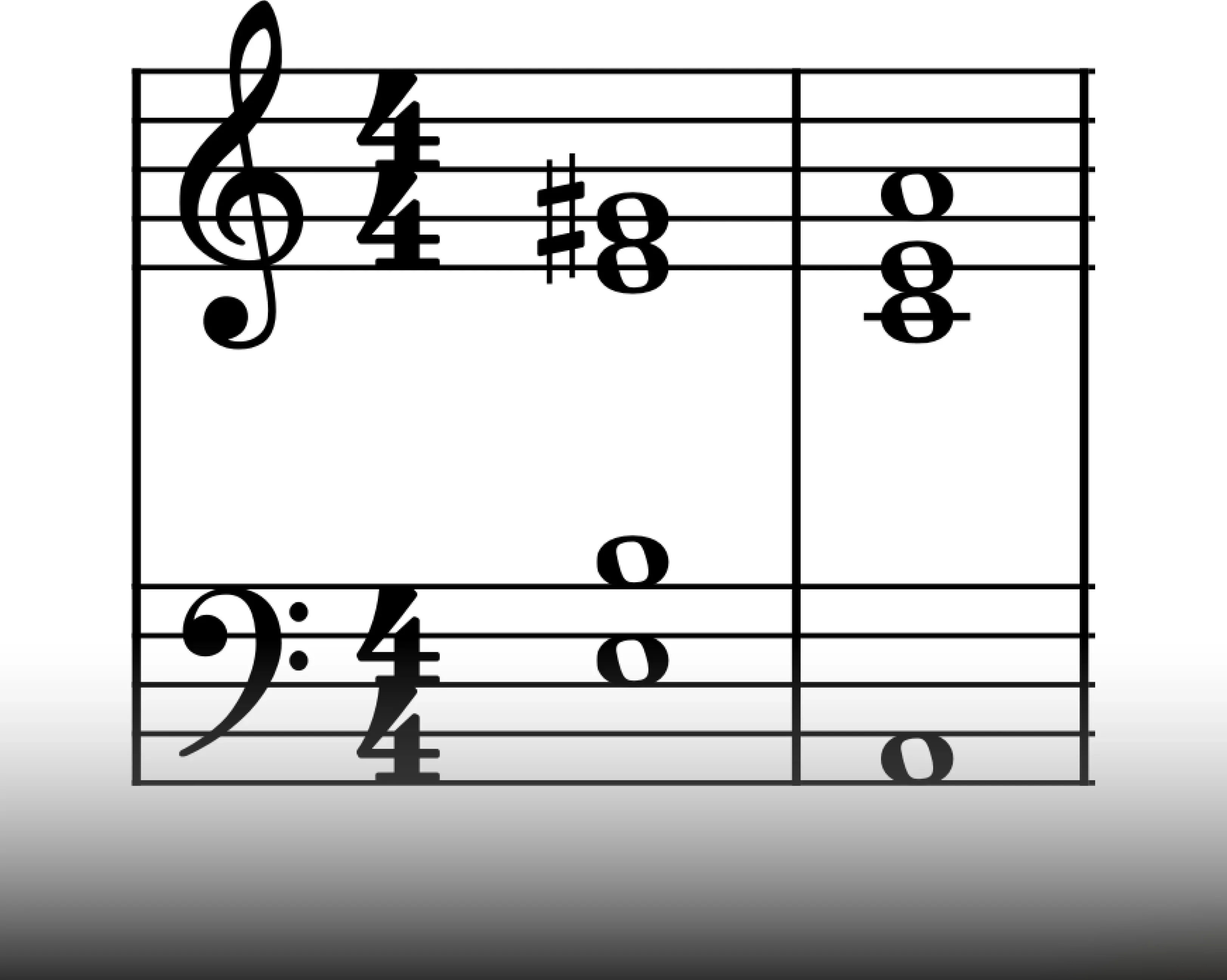

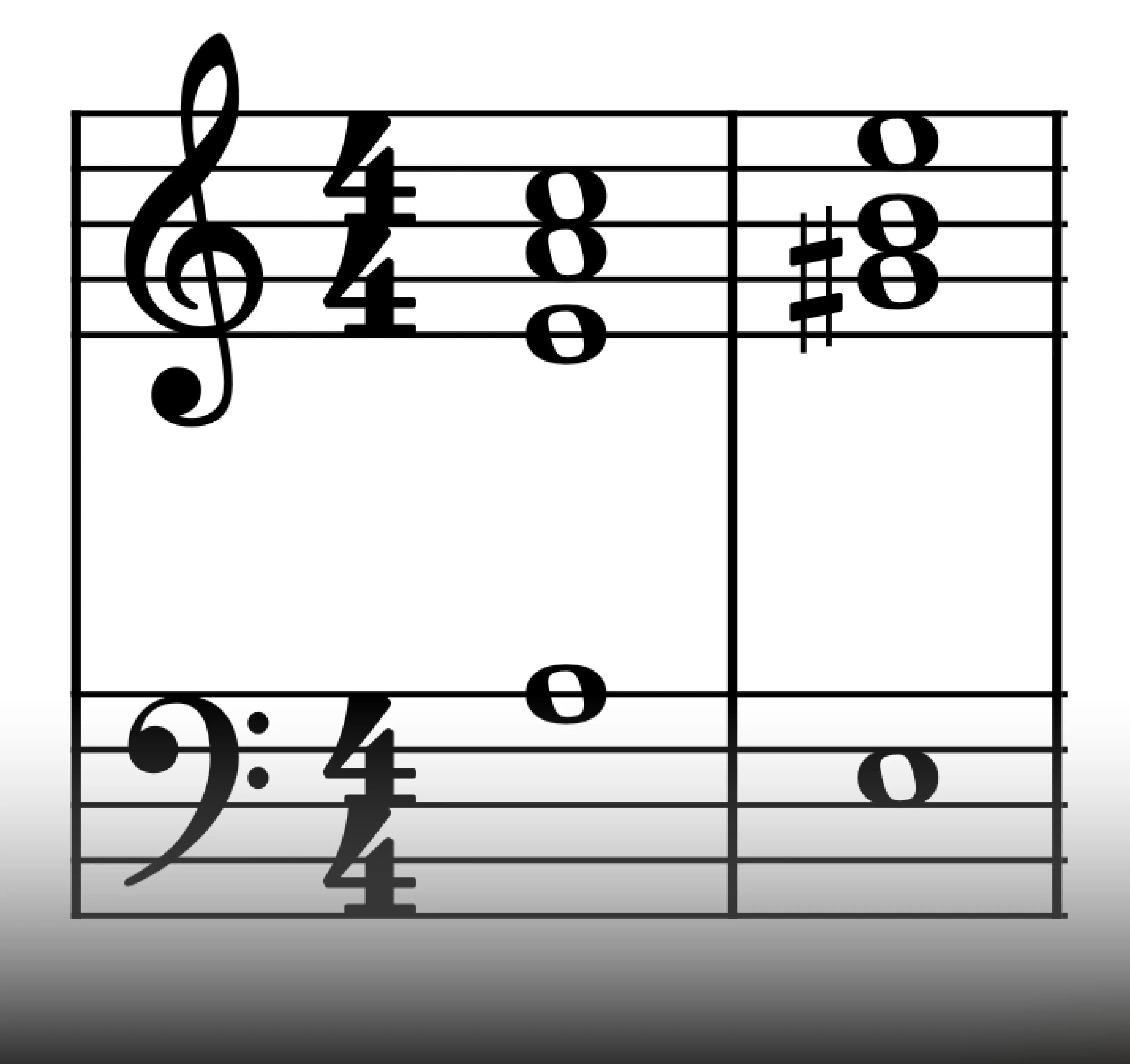

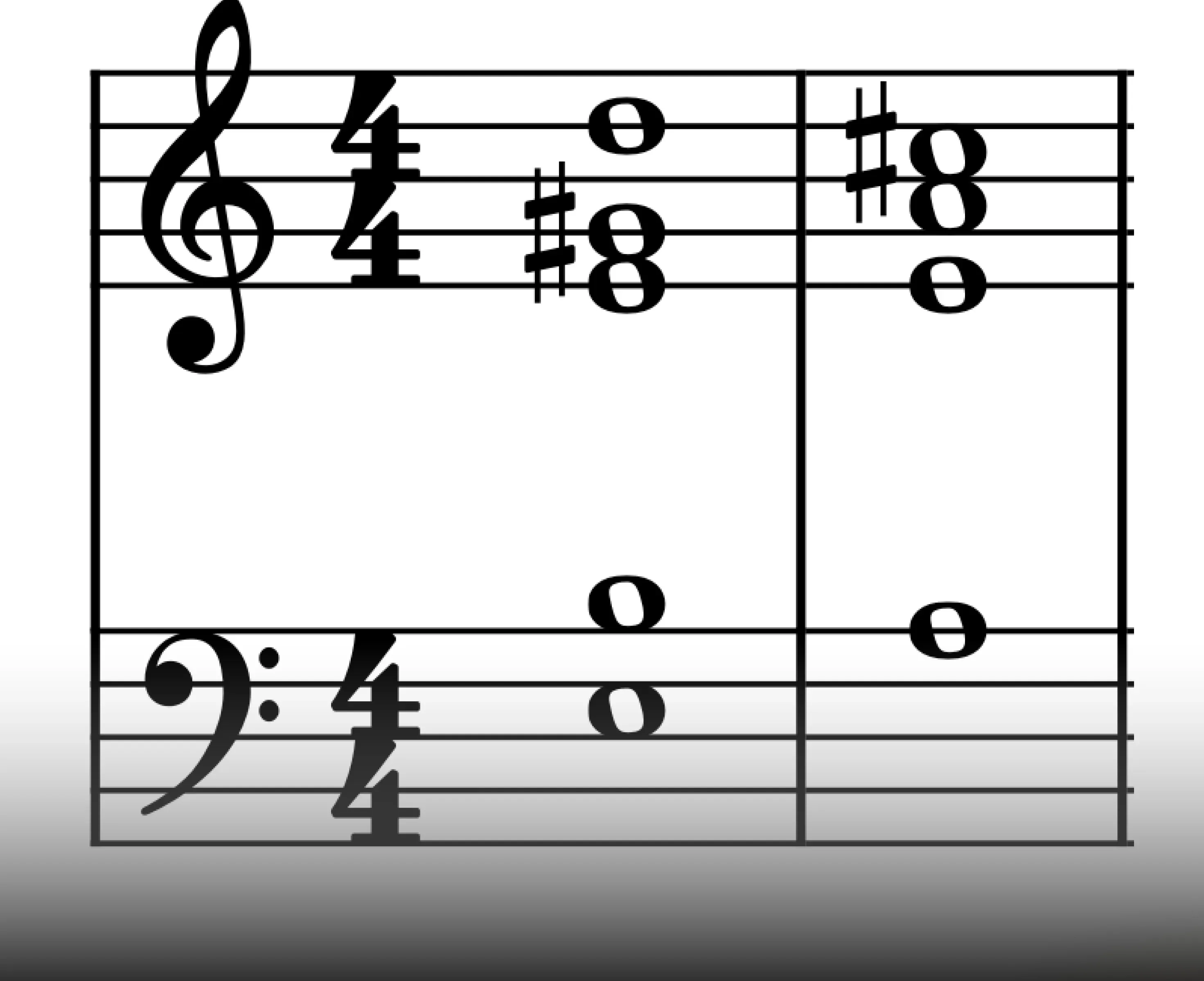

Perfect Cadence

Dominant → Tonic (V - i)

Emaj → Am

This is the cadence with the strongest sense of resolution. To be a perfect cadence, you need to have a Major V chord resolving to the tonic.

An even stronger resolution comes from the Dominant 7th chord resolving to the tonic.

Emaj7 → Am (V7 - i)

To be considered a perfect cadence, both chords in the interval must be in root position, meaning the root of each chord is the lowest note. How you distribute the rest of the notes doesn’t matter. Although, some argue that the highest voice of the I chord must also be the root of the tonic to be a perfect cadence, because this gives the strongest sense of resolution.

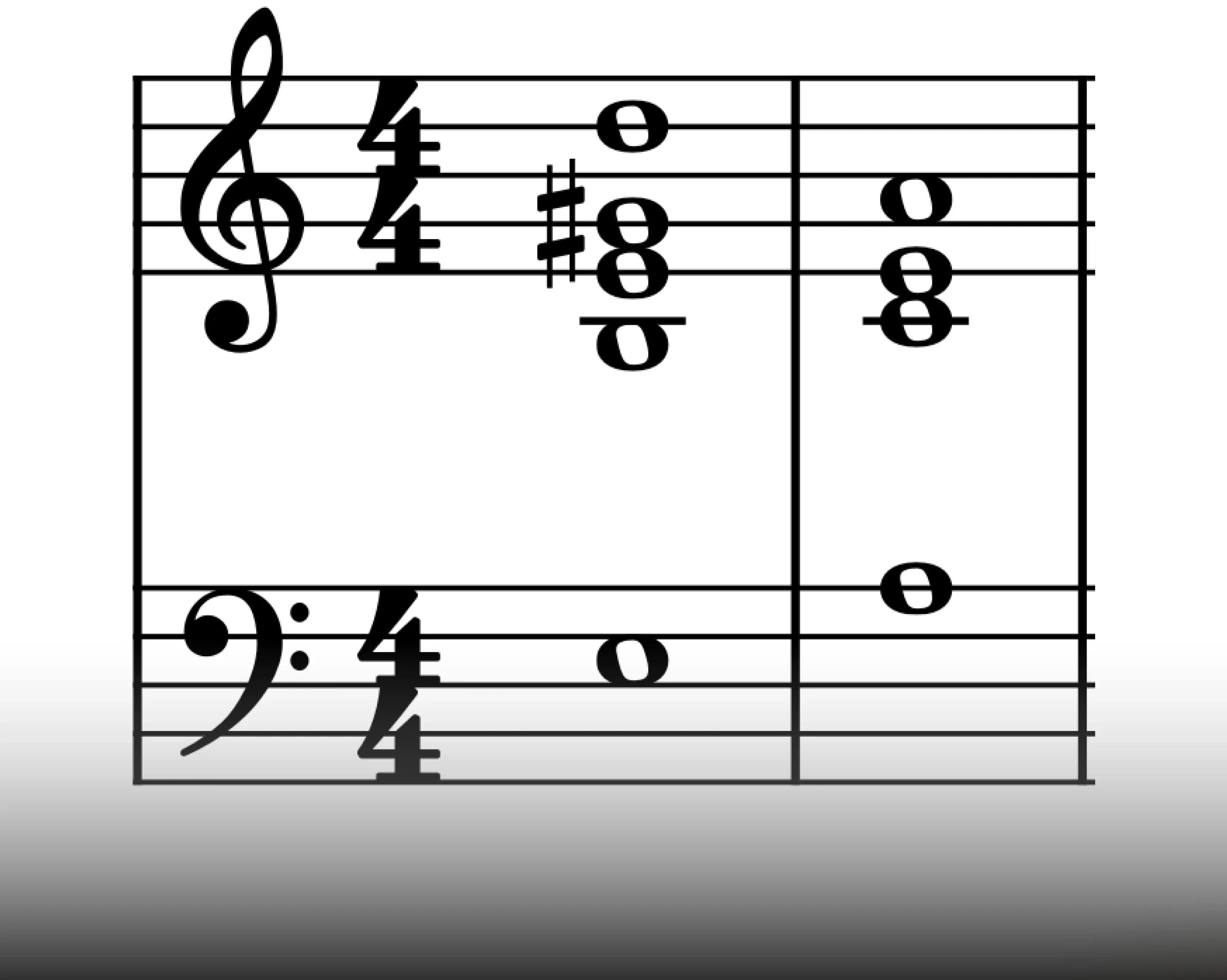

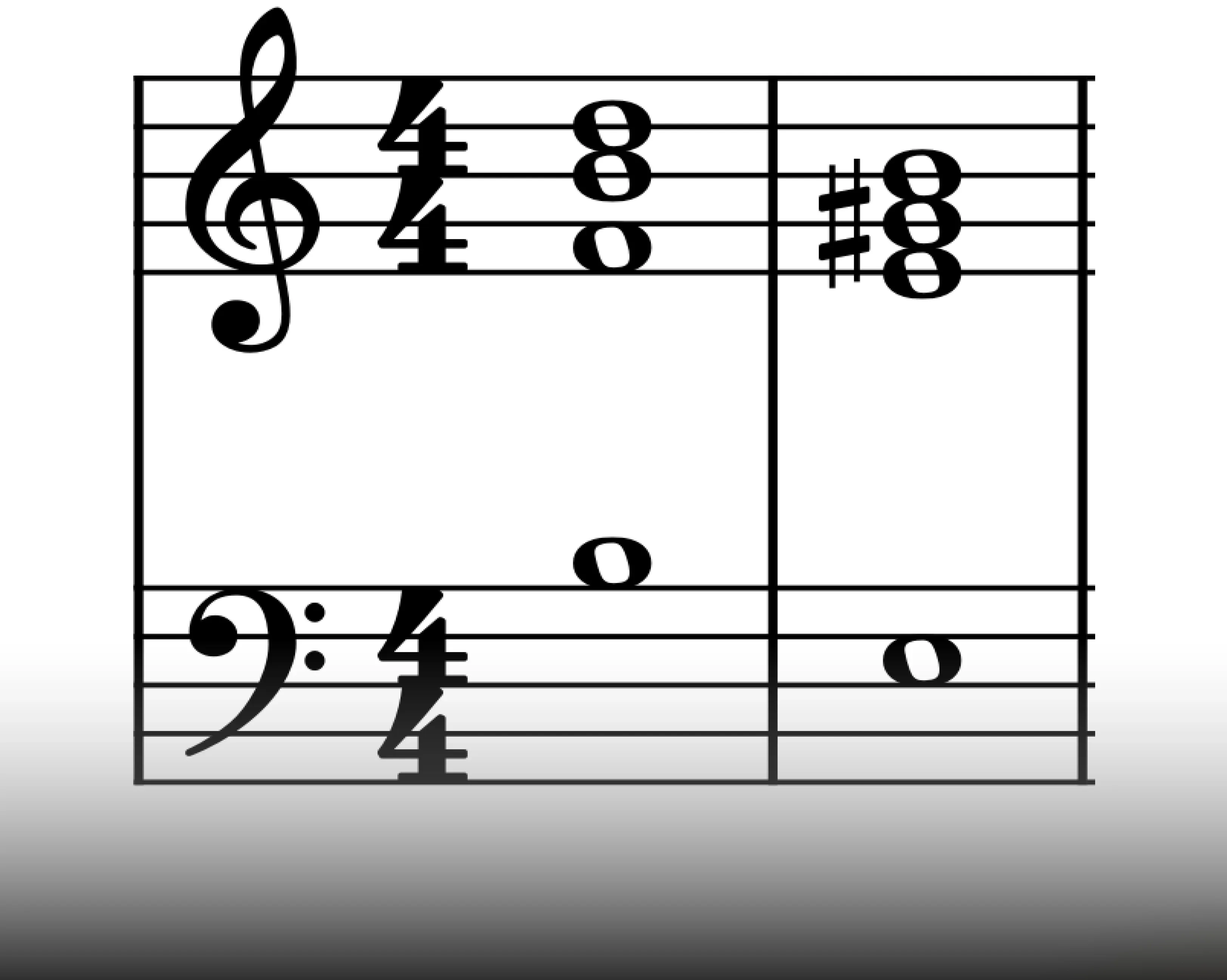

Plagal Cadence

Subdominant → Tonic (iv - i)

Dm → Am

The plagal cadence has a softer finish compared to the more definite resolution in the perfect cadence.

Plagal cadences are frequently heard in traditional hymns which end with the IV - I progression to the word “Amen”. Thus, this cadence is known as the “Amen cadence”.

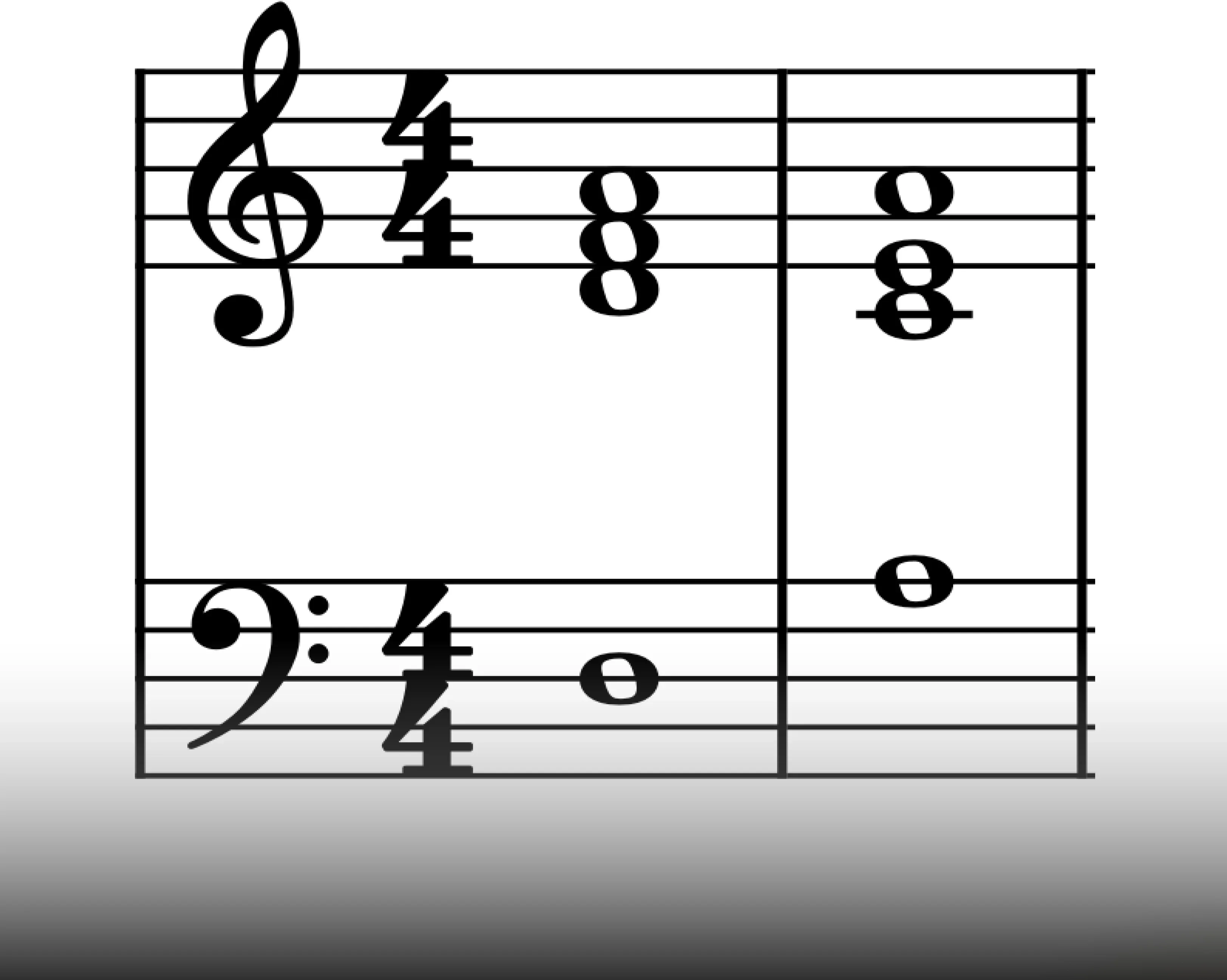

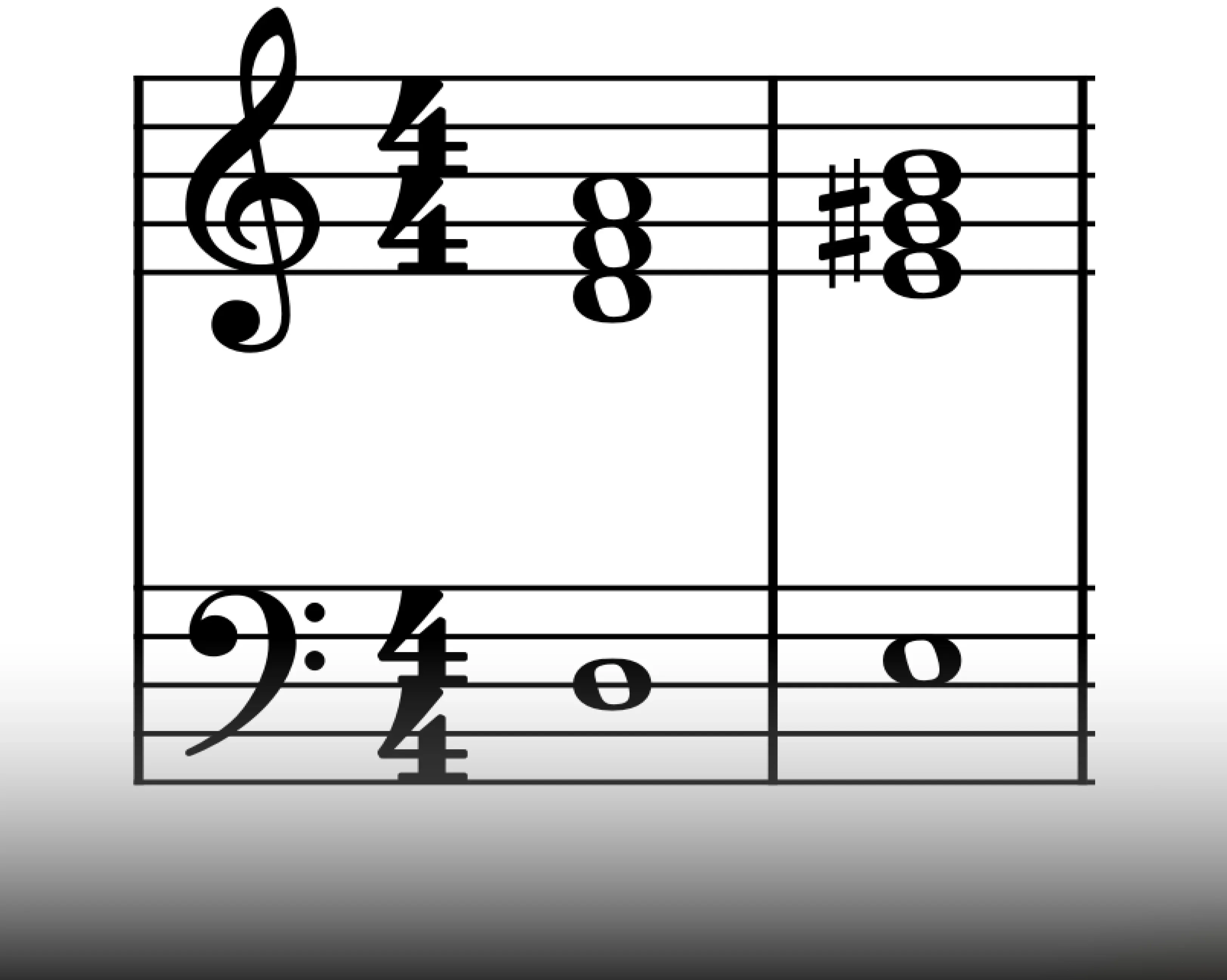

Half Cadence

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (i / ii / iv → V)

Am → Emaj

Bdim → Emaj

Dm → Emaj

The half cadence ends on the 5th scale degree, the Dominant. Since this ends on the most unstable chord we don’t get the sense of completion, like we do in the previous cadences. In terms of punctuation, this is more of a comma or sometimes a question mark.

Interrupted Cadence

Major Dominant to Submediant (V - VI) - Emaj → Fmaj

This is a cadence that appears to be heading towards a strong resolution, like V - i, but then goes in a different direction and ends on a secondary chord, most often Major VI in a minor key.

Picardy Third

Dominant 7th to Major tonic (V7 – I) - Emaj7 → Amaj

If you end a musical phrase in a minor key on a Major tonic, it’s called the Picardy third. The “third” in question refers to the raised minor third of the tonic, making it a major chord. This is a great technique for resolving on a more uplifting tone compared to the inherent somber quality of the minor tonic.

Common Chord Progressions in A minor

Here we’ll look at some great chord progressions in A minor. Pay extra attention to how some chords are used. For example the mediant or submediant as tonic substitutes and specific cadences.

Just beware that not every last two chords of a chord progression equals a cadence. A cadence is a specific style of punctuation, not just any last chords of a phrase.

Let’s dive into common chord progressions in A minor:

i (Am) - VI (F) - III (C) - VII (G)

The chorus of Johnny Cash’s “Hurt” uses this chord progression. The only real major contrast we get in this chord progression is the G Major. The first three chords, Am - C - F, transition very smoothly because each chord shares two notes with the next chord.

i (Am) - VII (G) - VI (F) - VII (G) - V (E) - i (Am)

The Weeknd’s “Starboy” repeats the same chord progression in the verse and the chorus, but he’s using some nice tricks to keep it interesting.

The first repetition of this progression is I (Am) - VII (G) - IV (F) - VII (G). What’s special here is that the A minor in the chorus is played in 2nd inversion, which means the E in the lowest note of the chord, and this makes it less stable. This is a good way to hint at a full resolution, without properly delivering it. This keeps the listener engaged.

Finally, at the start of the chorus the tonic is fully resolved, which makes the chord much more powerful. The second repetition of the chorus also uses a perfect cadence to punctuate the entire musical phrase.

i (Am) - III (C) - IV (D) - VI (F) - I (Am) - III (C) - V (E) - I (Am)

In “House of the Rising Sun” by The Animals we get a non diatonic chord. Diatonically, the IV chord should be a minor chord, but here it’s a major chord. We can think of this as a parallel substitution chord, or that the song is in the A minor Dorian mode. We return to parallel chords and how to use them further down.

Similar to the previous example, the second set of bars include the perfect cadence.

VI (F) - VII (G) - i (Am) - III (C) - VI (F) - VII (G) - V (E) - i

Songs in A minor don't need to start on the A min chord. Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance” starts with the interval of VI to VII which instantly creates anticipation that resolves perfectly with the vocal melody singing the hook “Caught in a bad romance”.

What makes this even better is that the second time she sings the hook, it aligns with the Major V which creates tension that ends in a perfect cadence. This is excellent song writing because it subverts expectations.

Repetition is key for a memorable hook, and this is a great way of making small changes so it doesn’t feel quite so repetitive. Pop music, in particular, tends to follow a very strict format. Little harmonic tricks like this can really make a song much more interesting.

VI (F) - V (E) - i (Am) - III (C)

The chorus in “Nightmare” by Halsey is powerful and energetic, partly because it starts on the VI which descends to the V chord. This is a satisfying somber major to minor interval that can have a big emotional impact.

The next two chords build up going from i to III and then reaching peak on the VI chord again as the chorus repeats.

It’s also worth noting that this song uses the minor v chord, which prevents the dominant from… well, dominating too much.

i (Am) - VI (F) - III (C) - V7 (E)

Here’s a very traditional and powerful chord progression with lots of energy and drive. We hear it in Fall Out Boy’s “This Ain't a Scene It's an Arms Race”. The verse and pre chorus are essentially only a I - V chord progression. Finally breaking free from the repetitive verse makes this chorus much more energetic.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

The key of a song, and the corresponding scale, are closely related, but not necessarily mutually exclusive. Songs in A minor aren’t limited to only using diatonic chords (chords based on each note in the A minor scale).

Diatonic chords are guaranteed to work on a harmonic level, but they’re not the only options. The use of the Major Dominant in a minor scale is a great example of a non-diatonic chord.

By raising or lowering scale degrees can create diminished, augmented, and different major or minor chords.

There are also options to modulate to the relative key, which we’ll look at next.

Relative Major: C Major

Every minor key has a corresponding major key, and vice versa. These two keys share the exact same notes but differ in tonal center and chord functions.

The relative major:

In a minor scale, the relative major is found on the third scale degree, the mediant. In A minor, that’s C.

The relative minor:

In a major scale, the relative minor is found on the sixth scale degree, the submediant. In C Major, that’s A.

In a major scale, the relative minor is found on the sixth scale degree, the submediant. In C Major, that’s A. These two scales share the exact same notes, but have different tonics. This changes the chord functions and role of each chord. Read about Chords in C Major for more details on this key signature.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

Because the key signatures are related, you can easily create variety and harmonic interest by modulation between the two with only a subtle tonality change. Modulating between relative keys is common and allows you to create different moods for different sections of the song.

Songs in A minor can modulate to C Major for more energy and if the song needs to be more uplifting. Conversely, going to the relative minor key chord provides a somber and introspective tone.

Adding Complexity to A Minor Chord Progressions

Temporarily breaking free from diatonic chords is a great way to add harmonic interest to the music. Understanding the principle of music theory allows you to expand the song’s color palette to enrich the harmonic landscape.

Parallel Chords

In its simplest form, parallel chords involve using accidentals to change the quality of a chord. If you raise the third of the subdominant from F to F♯ you get a D major chord. Changing the quality of any chord in your can have a surprising effect and take the music to an unexpected direction.

Make sure not to use too many parallel chords. Otherwise you risk losing focus and stability of your piece. Use parallel chords with care and with good intention.

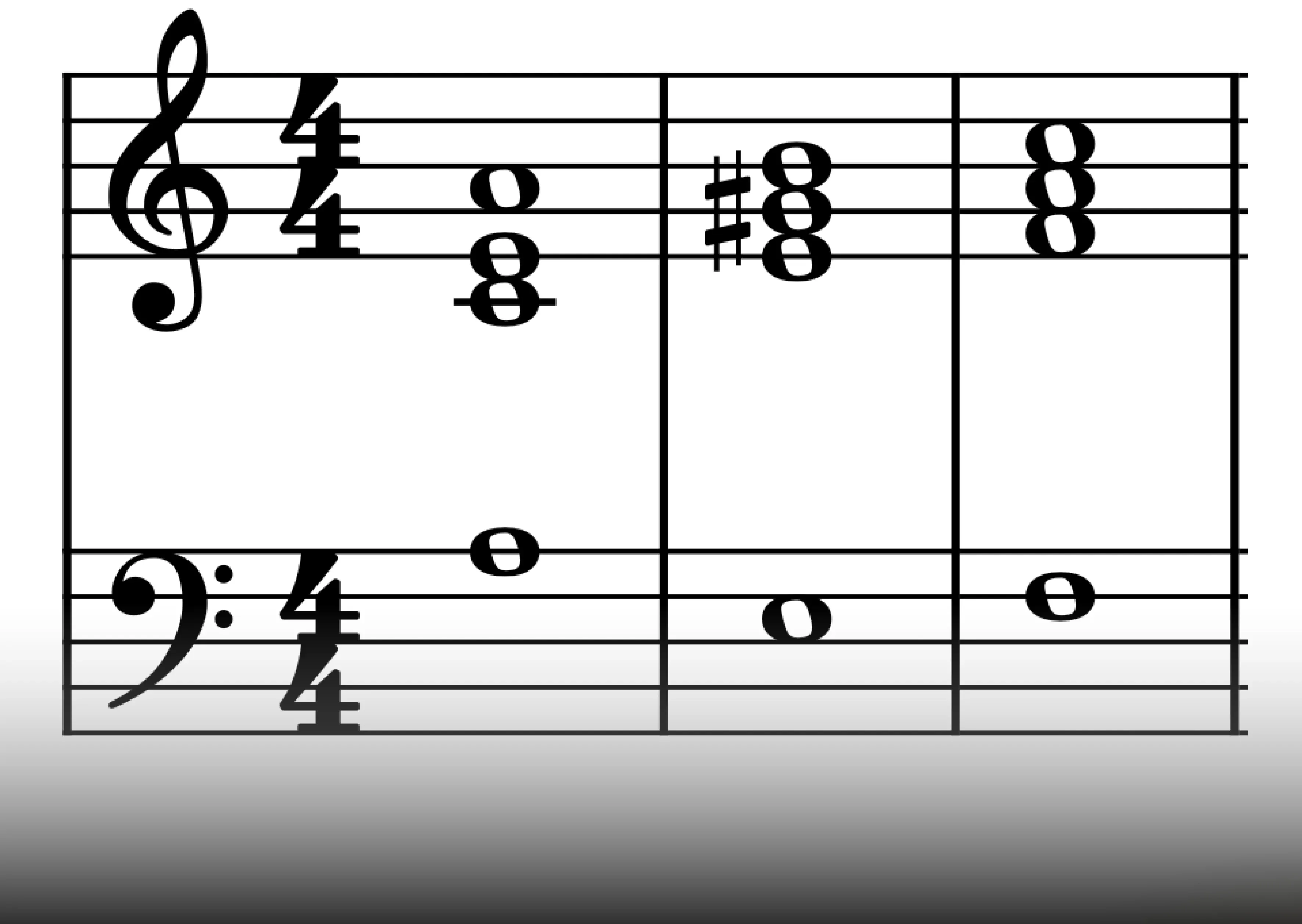

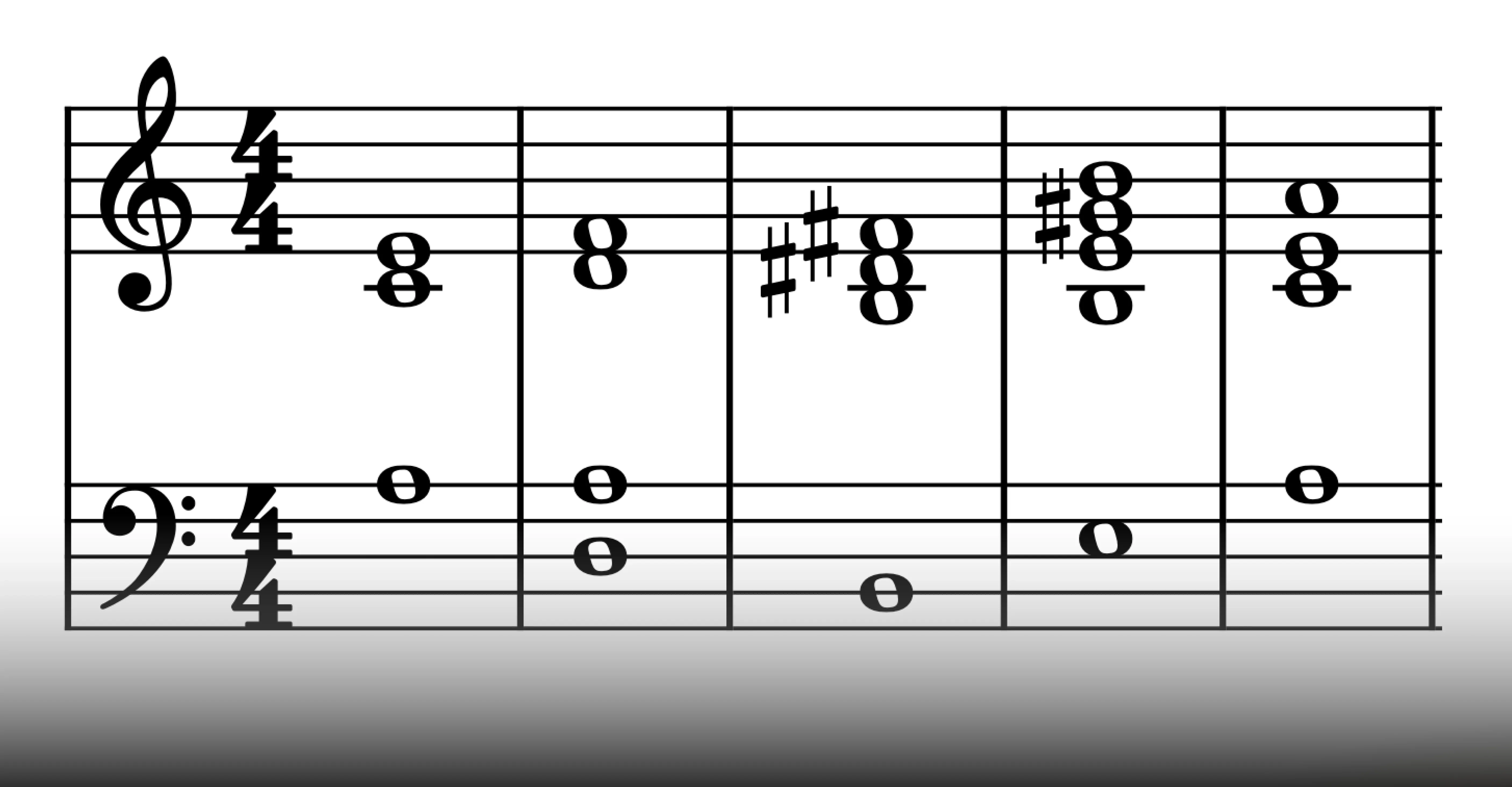

Secondary Dominants

A secondary dominant makes the chord you're moving to a temporary tonic by preceding it with its own dominant chord. Effectively, you’re creating a V - I(i) interval from a different key within your chord progression. This can enrich the harmonic texture of the song.

Dominant chords are built on the fifth scale degree. The most common secondary dominant chord in chord progressions is one based on chord V. In A minor, chord V is Emaj, which makes Bmaj the dominant of the dominant.

Example:

We can add a secondary dominant chord to a simple i - V - i progression to hear how much depth interest this technique can add to your music.

i - V/V - V - i

Am - B - E - Am

By just scratching the surface in music theory we open up new worlds of possibilities and get a whole new color palette for our music. When we start to see how chords and notes are related to each other we can create much more interesting chord progressions.

How Musiversal Can Help You Write the Best Music

Understanding the chords in A minor and how you can relate them to other keys is fundamental to create interesting chord progression that goes beyond just the simple and traditional ones.

It's beneficial when you record with Musiversal’s session musicians to communicate what you want performed and to be able to communicate your musical ideas clearly to get the most out of your recording sessions.

If you can explain the use of secondary dominants in your chord progression they’ll approach it appropriately. Alternatively, if you write “V/V” in the chord chart, instead of just the chord name, our session musicians can structure their performance to connect the chords in the intended way. Knowing the purpose and motivation behind a chord change can help shape the performance.

Non-scale chords can be a bit jarring if they’re not written or performed with the correct purpose or intention behind them.

If you need help making a chord progression or add interesting harmony to your melody, consult our pre production and songwriting experts. With the Unlimited membership you not only have around-the-clock access to 100+ professional session musicians, but also songwriters and producers to help you write better music.

Join The Musiverse: Your free space to connect, create, and compete.

Collaborate with global creators, level up in live workshops, and win exclusive prizes. Join the community today!

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist