A Comprehensive Guide to Crafting Chord Progressions in D Major

Master chord progressions in D Major by analyzing famous songs. Explore diatonic and chromatic harmonies, secondary dominants, chromatic mediants to unlock your unique sound.

Introduction

This article explores the art of crafting interesting and captivating chord progressions within the key of D Major. We'll begin by analyzing chord progressions from popular songs and look at the underlying theory to help you understand the theoretical principles that contribute to their effectiveness.

Then we’ll look at how you can enrich your chord progressions. We'll delve into techniques like secondary dominants, parallel chords, and key modulations, explaining the music theory behind these concepts and how they can be used to create more sophisticated sounds.

Finally, we'll discuss the importance of cadences - how to strategically punctuate your progressions to effectively build and release musical tension.

Building Blocks of D Major

To write intriguing chord progressions in D Major, it’s important to understand the foundation of the key signature and the function of each individual chord.

We’ll only touch on it briefly here. Read “Chords in D Major: A Comprehensive Guide” for an in-depth guide on the foundations of chords in D Major.

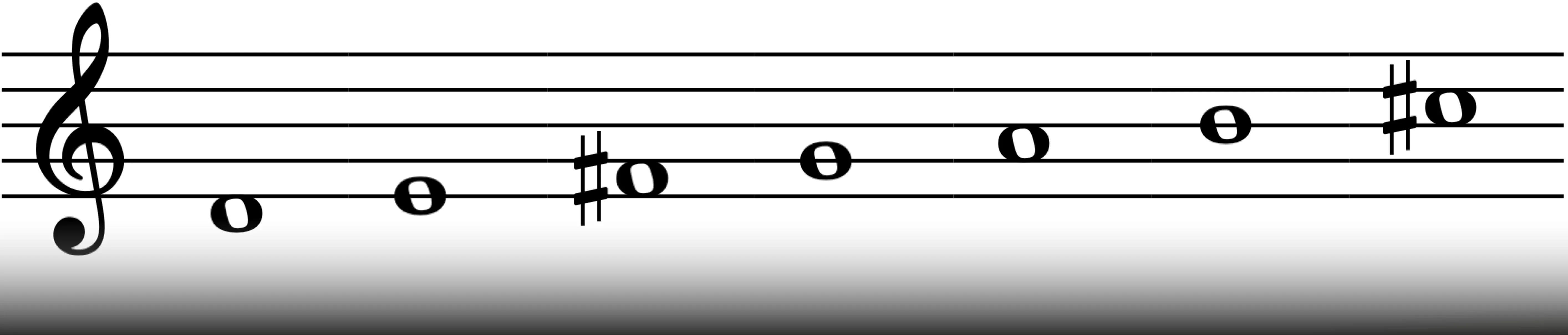

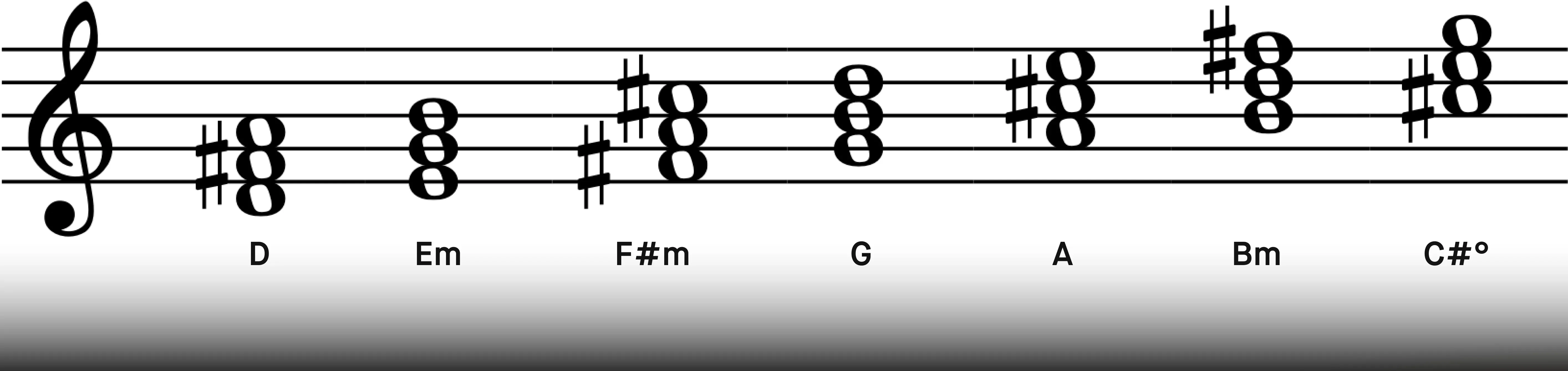

The diatonic chords in D Major are based on each 7 notes from the D Major scale.

Using only these notes we can build the following chords in a D Major key signature: D Major, E Minor, F# Minor, G Major, A Major, B Minor and C# Diminished.

Common Chord Progressions in D Major

The following D Major chord progressions offer a glimpse into the world of harmonic possibilities. You'll find examples incorporating techniques like secondary dominants and parallel chords (explained in detail later).

Study these progressions to understand the harmonic role of each chord. They're versatile enough for various styles, including rock, EDM, country, indie, classical, and pop. Learning how different genres use harmony will greatly enhance your songwriting.

Let’s look at how D Major chords are used in popular songs.

I (D) - I (D/F#) - IV (G) - V (A)

This simple yet effective progression, built on primary chords, forms the foundation of Ed Sheeran's"Thinking Out Loud". The inverted I chord (with an F# bass) creates forward motion and drives the music forward while maintaining harmonic stability through its consistent chord quality.

I (D) - V/V (E7) - V (A) - IV (G) - V (A)

The standout feature of this chord progression, found in ABBA's"Waterloo"is the secondary dominant (V/V) chord. It's not a diatonic chord in D Major, but it creates harmonic interest by briefly suggesting the key of A Major (the dominant key). It creates a strong pull towards the A Major making the resolution to A feel very satisfying. This is a classic technique for adding interesting harmonic color and complexity to a chord progression.

ABBA uses chord inversions to create a descending bassline, giving the song its sense of forward motion. The progression moves from the tonic (D) in root position, through E7/D, A/C#, and G/B, before resolving to the dominant (A). This dominant ending creates tension and sets up a smooth transition to the next section.

I (D) - ii7 (em7) - IV (G) - V (A)

This foundational pop music progression, exemplified by Taylor Swift's"Our Song"provides a strong harmonic framework. Its smooth chord transitions and satisfying resolution, driven by the dominant-tonic relationship, create an emotionally resonant effect. Its simplicity and versatility allow it to be adapted to various genres and styles, making it a go-to choice for songwriters.

The minor ii chord, especially as a minor 7th, creates a somber, mellow quality and adds a hint of instability.

IV (G) - I (D) - V (A) - IV (G) - I (D)

Using only primary chords can get you a long way. One of the reasons for this progression's effectiveness is its less conventional starting point on the subdominant chord. More often than not, a chord progression begins with the tonic chord, establishing a clear tonal center.

However, by starting on the subdominant, the progression immediately generates a sense of anticipation and forward momentum. This chord progression is heard in “Bad Moon Rising” by Creedence Clearwater Revival.

I (D) - V (A) - vi (Bm) - IV (G)

This seemingly simple chord progression has a timeless quality. The core of the progression is the tonic-dominant relationship which establishes the key and creates a sense of expectation.

The inclusion of the relative minor adds a touch of introspection, creating a momentary shift in harmonic color. The subdominant provides harmonic support and smooth transitions, often acting as a"pre-dominant"to set up the return to the dominant, and ultimately the tonic (D Major).

It’s the simplicity that makes it versatile and adaptable to various genres and styles, from pop and rock to folk and country. Its basic structure can be embellished to create a wide range of musical textures.

A great example of this is Men at Work's"Land Down Under". The song starts in B minor. For the chorus, modulates to the relative key of D Major and plays these simple chords. The shift in the tonal center makes this chord sequence more unexpected and interesting.

I (D) -iii (F#m) - vi (Bm) - IV (G)

This progression evokes a hopeful feeling. While the two consecutive minor chords introduce a touch of melancholy, the subsequent major IV chord infuses the music with optimism. The choice of the subdominant G Major, instead of the dominant, creates a gentle, hopeful atmosphere, as heard in One Republic's"Secrets”.

I (D) - II (E) - iv (G) - I (D)

David Bowie incorporates two chromatic chords in the progression from “Fantastic Voyage”. He uses Major II chord in place of the diatonic E Minor; and G Minor instead of G Major. These two chord choices create an unexpected harmonic shift that, in true Bowie fashion, makes the harmony feel more unstable and unpredictable.

IV (G) - I (D) - V - I (Dadd9)

The chorus of Owl City's"Alligator Sky"gets its energy partly from the IV chord that starts the progression. While most pop and rock songs begin their main sections (verses and choruses) on the tonic for a sense of stability,"Alligator Sky"uses the IV to create a feeling of forward momentum and freshness. This technique, more often used in bridges, makes the chorus stand out.

vi (Bm)- iii (F#m) - V (A) - IV (G) - V (A)

This is the chord progression used by Avril Lavigne in her hit song “Girlfriend”. Both verses and the chorus are major-centric. So infusing the song with these minor chords really changes the mood in the birge of the song. The V-IV-V progression builds anticipation for the familiar, anthemic chorus, which also opens the song.

I (D) - V/V (E7) - vi (Bm) - V (A)

This chord progression, with its subtle lift from a secondary dominant, forms the foundation of the Goo Goo Dolls'"Iris". Although constructed primarily from major chords, the song has a distinct melancholic quality and feels rather minor.

However, an important reason for the song’s signature sound lies not only in the progression but also in the unique guitar tuning (BDDDDDD). This open and resonant tuning dramatically alters the way the chords are voiced, contributing significantly to the song's emotional impact.

This shows how unconventional tunings, instrumentation, and a personal touch can drastically change how a chord progression is experienced by the listener.

Don't feel pressured to create completely unique progressions every time. A great approach is to adapt a classic progression and add your personal touch. Learning to personalize existing progressions is a great way to develop your own voice.

I (D) - V (A) - ii (Em) - IV (G)

This is a classic chord progression that has been used countless times across genres. Aerosmith features it in “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing”. The Minor ii chord stands out as particularly heavy when it follows two major chords. This effect comes from the larger leap between V and ii, which feels more dramatic compared to the more common V-vi interval.

This exact chord progression is also used in the chorus to Oasis’ “Don’t Cry You Heart Out”.

I (D) - ii (Em) - IV (G) - V (A)

Labrinth and Emeli Sandé's"Beneath Your Beautiful"provides another compelling example of the Minor ii chord's ability to create a somber atmosphere. While this chord appears in countless songs across genres, its strategic placement as the second chord in this particular progression is key to the song's mellow and melancholic feel. This deviation from the common practice of placing the minor chord third adds a unique layer of emotional depth.

vi (Bm) - V (A) - IV (G) - ii (Em) - I - V (A) - IV (G)

In"Caring Is Creepy", The Shins uses a D Major progression that begins on the vi chord (Bm), functioning as a tonic substitute. This clever choice subtly strengthens the tonic when it arrives. Further enhancing the progression is the use of sus4 chords.

Towards the end of the phrase the chords alternate between D Major and Dsus4 and A Major and Asus4. This creates a dynamic interplay of resolved and unresolved tension.

I (D) - vi (Bm) - VII (C)

Here are three simple chords that have been used countless times in music. However, it’s worth noting that C Major is not a diatonic chord in the key of D Major. In D Major, the 7th note is C#. By lowering this note to C, the progression shifts into the Mixolydian mode.

The Mixolydian mode is known for its slightly less formal, more relaxed sound, often associated with folk, rock, and blues music. This subtle alteration adds a unique flavor to the progression, giving it a more open and melodic quality. This small change can have a big harmonic impact, helping create a mood that feels familiar yet distinct from the standard major scale.

We hear this mixolydian progression in “Lights” by Journey.

I (D) - V/vi (F#) - IV (G) - iii (F#m) - ii (Em)

“Mardy Bum” by Arctic Monkey’s uses this chord progression in the verse. Using both F# Major and F# Minor is what gives this progression its unique quality while giving the song its signature British garage punk feel.

Spice Up Your Chord Progressions: Creative Uses of D Major Chords

Chord Inversions

Chord inversions offer a powerful way to create smoother and more natural transitions between chords. While triads in root position are fundamental, over-reliance on them can result in a monotonous sound. By inverting chords—changing the bass note and rearranging the notes—you can add harmonic variety and subtle shifts in stability, leading to more engaging progressions.

For more information on chord inversions in D Major, explore our article “Chords in D Major: A Comprehensive Guide”.

Non-Diatonic Chords

While the seven diatonic notes of D Major provide a solid foundation, exploring all twelve chromatic notes unlocks a world of harmonic possibilities. Used intentionally, chromaticism adds color, tension, suspense, and intrigue, making music far less predictable.

Mastering the use of all twelve notes, regardless of key, opens exciting new avenues for expression. These non-diatonic notes, when they alter a diatonic pitch, are called"accidentals"and are notated with sharps (♯), flats (♭), or naturals (♮) to restore a note to its original diatonic form.

Chromatic notes are especially useful for:

- Creating harmonic tension and instability

- Adding a smoother voice leading

- Modulating to new keys

- Increasing the song’s emotional depth

- Making your music feel less predictable

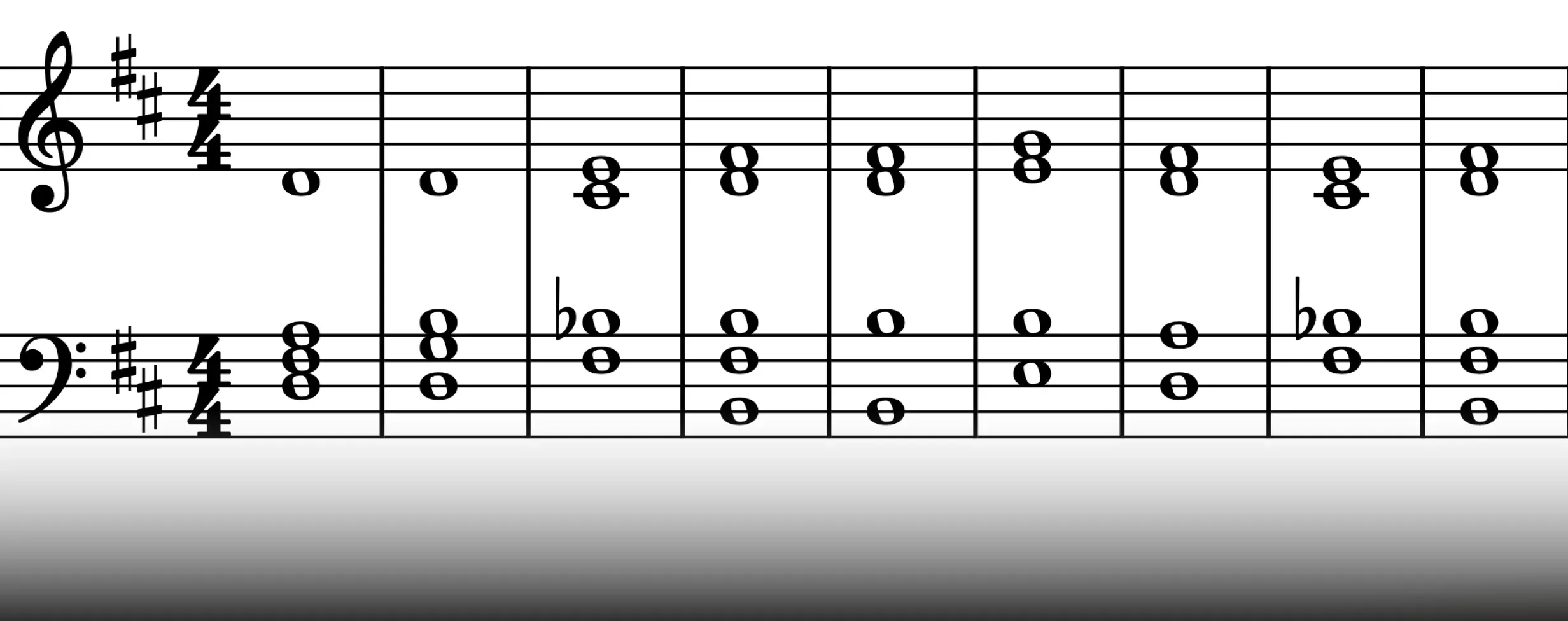

This chord progression demonstrates the use of a secondary dominant, incorporating an accidental.

Chords: D - G - E7 (a non-diatonic chord) - G - A

Developing your ear for intervals is crucial for composing and improvising. It allows you to instinctively identify both diatonic and chromatic notes, making it easier to determine the next chord in your music and even facilitate key changes.

A great way to internalize intervals is by associating them with familiar melodies. For more on this, check out our article"Ear Training: Songs to Practice Intervals"where we explore this topic and provide examples of well-known melodies showcasing each interval, both ascending and descending.

Secondary Dominants

The fifth scale degree is a cornerstone of Western harmony. Its inherent tension and resolution create a powerful dynamic between dominant and tonic chords. This relationship is so fundamental that it can be expanded upon and applied to chords beyond the basic key signature through the use of secondary dominants.

Secondary dominants allow us to temporarily"tonicize"or treat any chord within a key as if it were its own temporary tonic. We achieve this by borrowing the dominant chord from the key of that target chord.

This borrowed dominant, a perfect fifth above the target chord, is the secondary dominant. It creates a brief but strong pull towards the target chord, much like regular dominant pulls towards the tonic within the original key signature.

Let's use a practical example of how this works. Imagine you want to add some harmonic color and emphasize the submediant chord, B minor (vi), in your D Major progression.

B minor, while diatonic to D Major, can be given extra weight by temporarily treating it as its own tonic. To do this, we need its dominant chord. The dominant of B Minor is F# Major (V of vi), or more commonly, F#7 to add more harmonic color. This F# dominant 7th chord is the secondary dominant in this context, specifically the V7/vi (V7 of the vi chord).

Now, notice that F#7 contains the notes F#, A#, C#, and E. The A# is not in the key of D Major; it's a chromatic note. This is the note that gives the secondary dominant its characteristic sound and creates the temporary strong pull towards B minor.

The F#, therefore, creates a momentary sense of being in the key of B minor, even though the overall key of the piece remains D Major. This"tonicization"adds depth and interest to the harmonic landscape.

By using secondary dominants, you can create unexpected harmonic twists and enrich even simple chord progressions. They add a layer of sophistication and emotional depth, enhancing musical expression by creating a sense of momentary departure and return within the larger context of the original key.

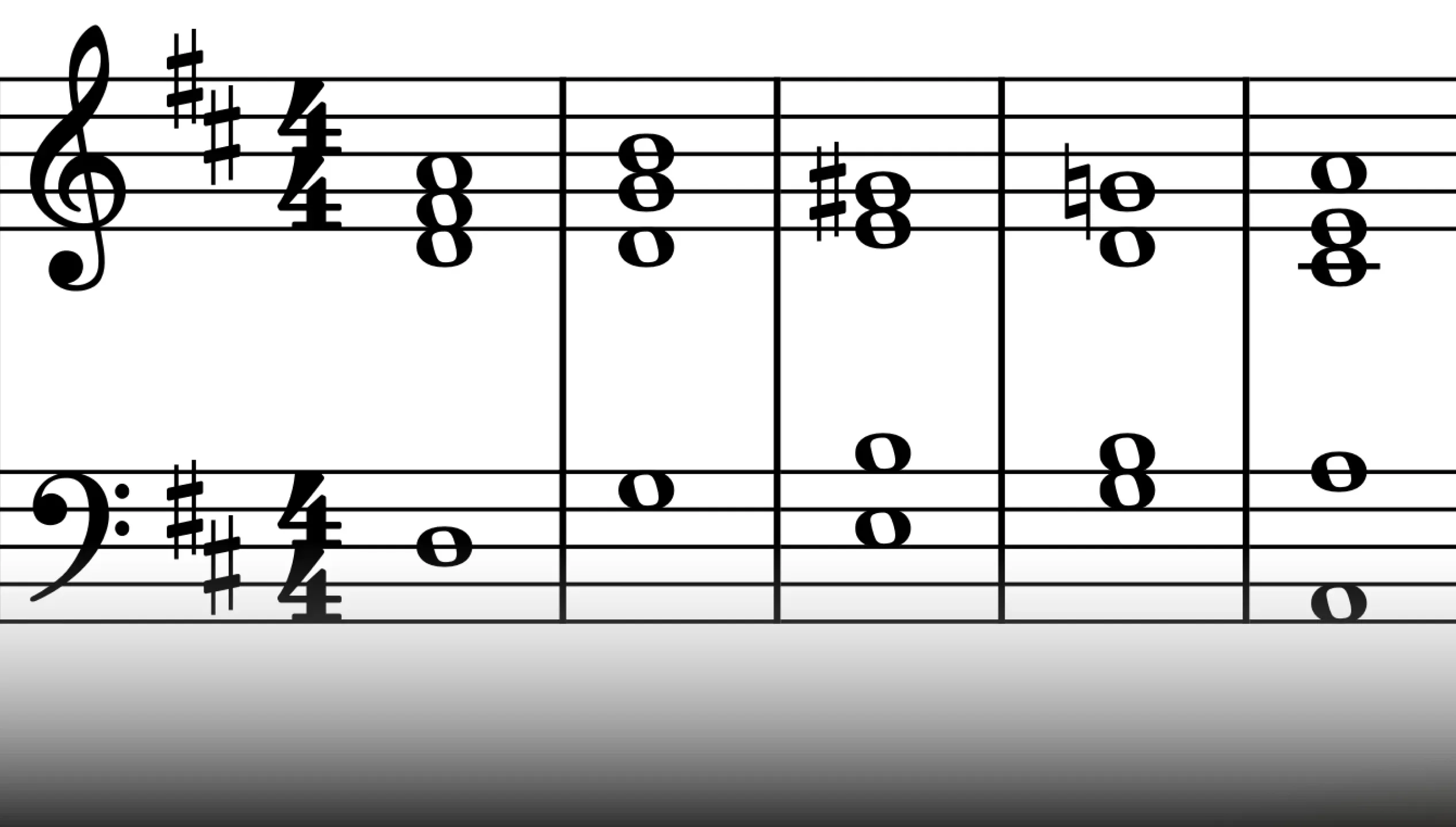

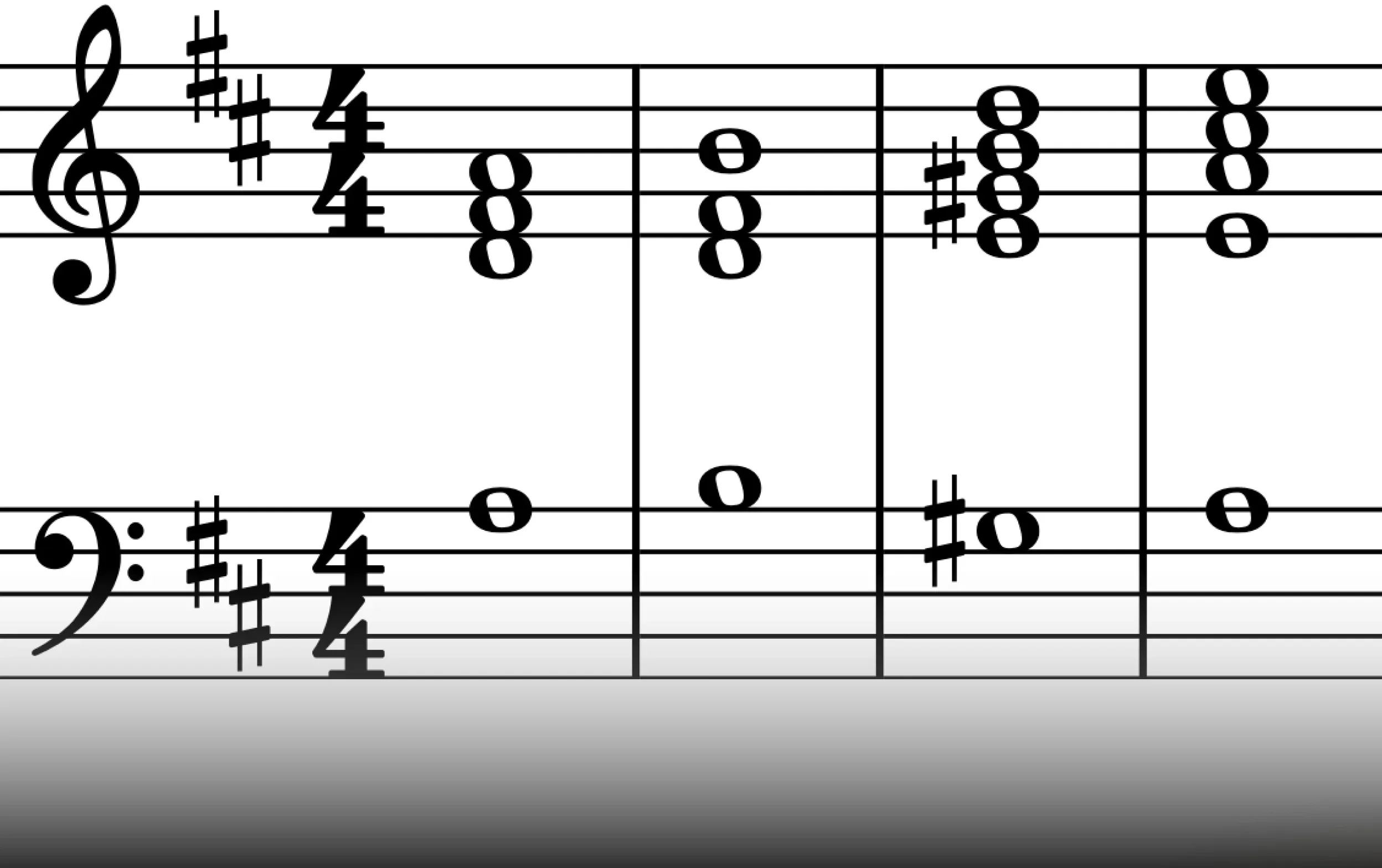

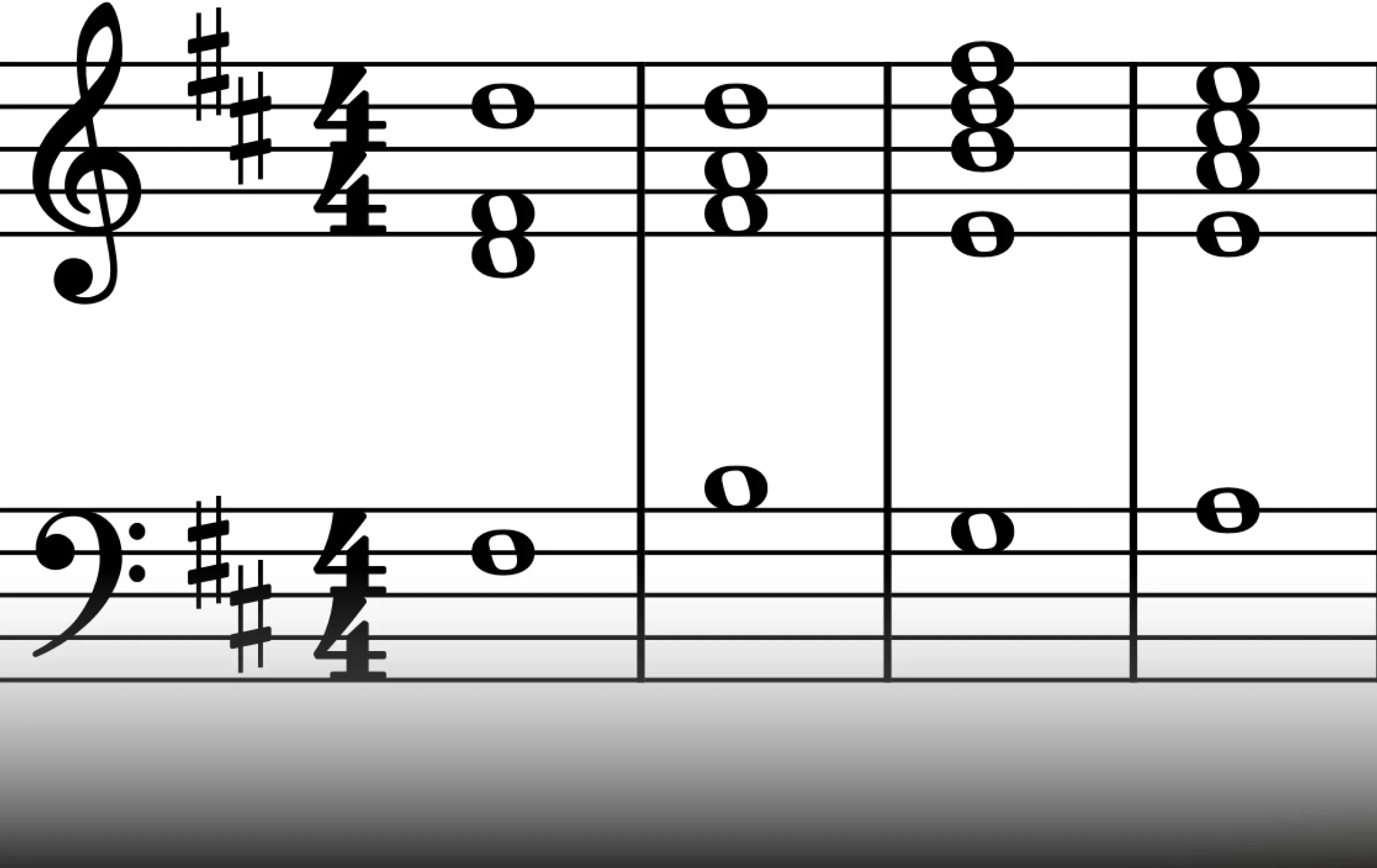

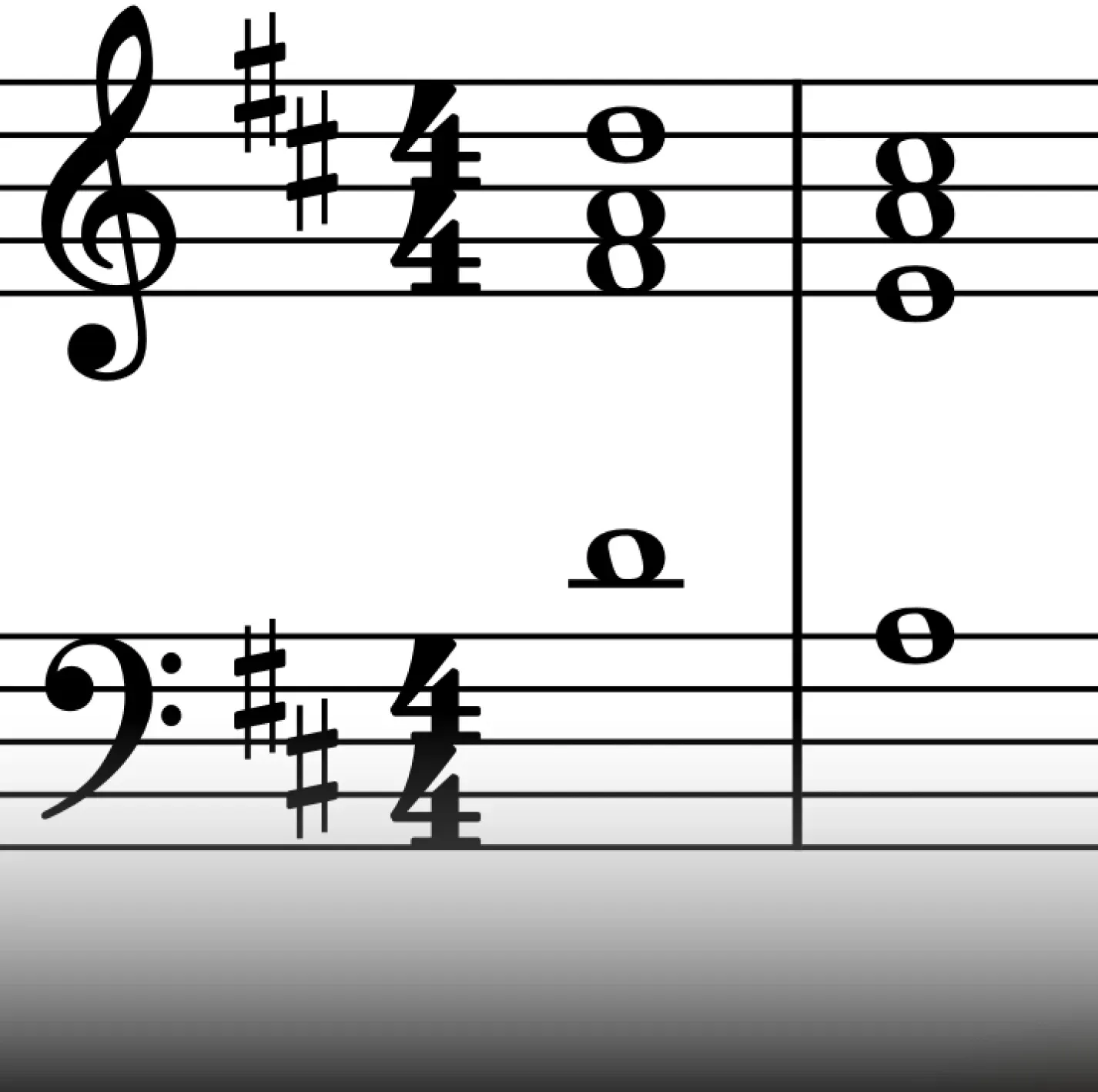

Here’s a quick three-chord progression using a secondary dominant to heighten the impact of the final chord.

Chords: D - F#7 (V/vi) - Bm

Next is an example where we tonicize the dominant chord by preceding it with its own dominant.

Chords: D- Bm - E7(V/V) - A

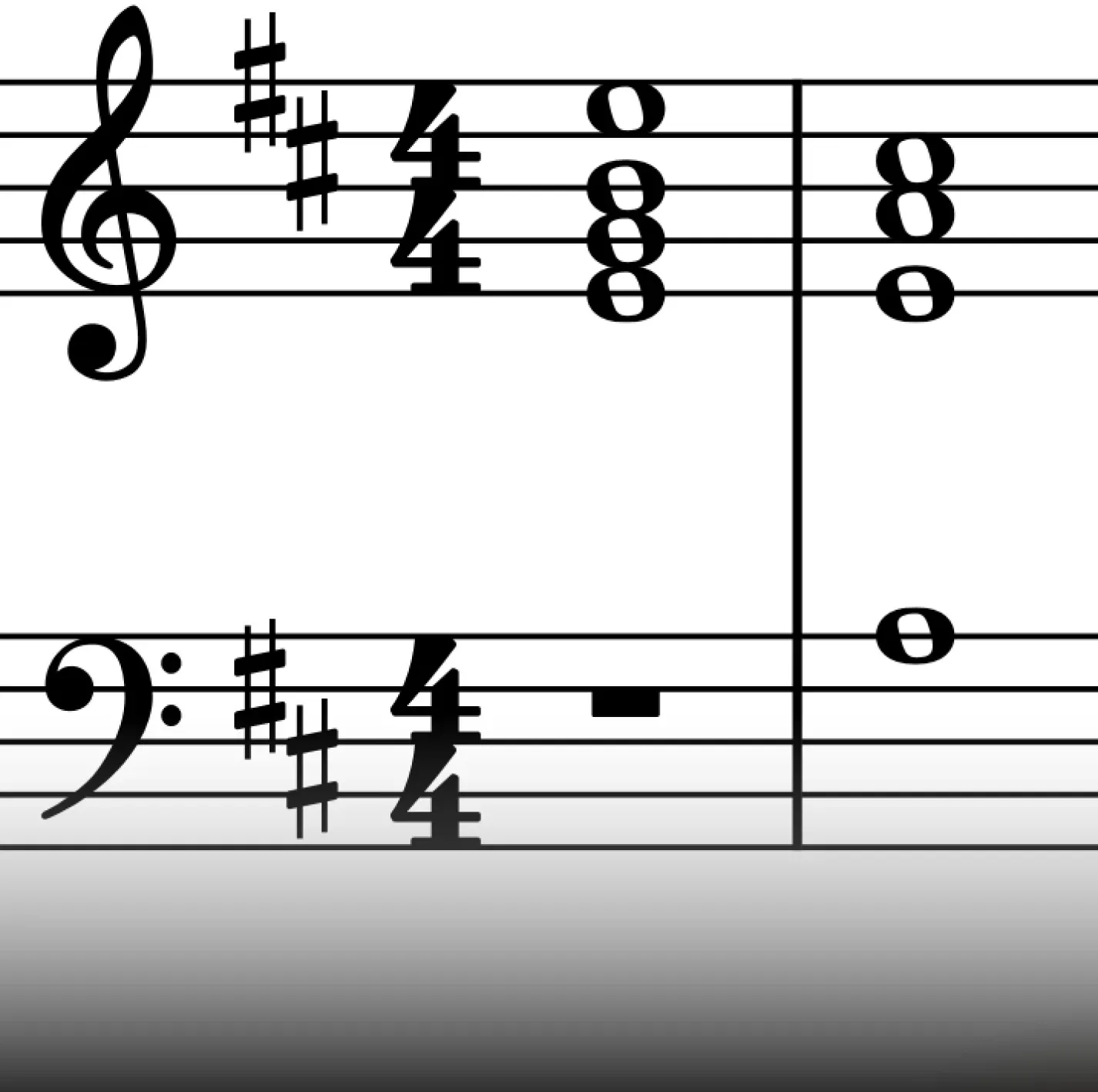

Here’s another example:

Chords: D/A - G - D/F# - E7 (V/V) - A - D

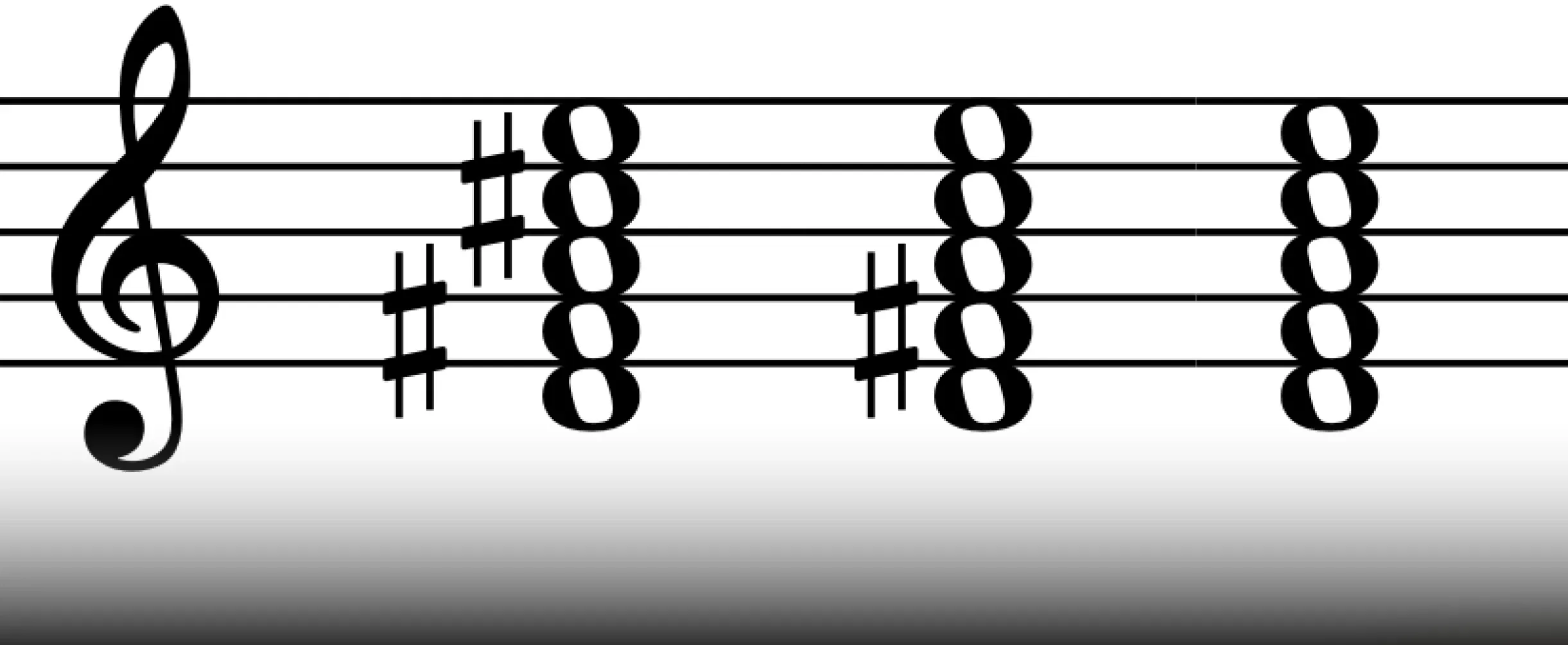

Chromatic Mediants

Chromatic mediants are a fascinating way to add color and depth to harmonic progressions. They involve chords that are related to the tonic by a third (either major or minor), but crucially, these chords contain notes outside the key signature, making them chromatic. However, they remain connected to the tonic due to the shared tones between them.

To be considered a chromatic mediant, the chord must be a third above or below the tonic. This interval relationship is essential. Chromatic mediants are derived from the basic mediant (iii) and submediant (vi) chords of a key. Starting from the tonic, you can create chromatic mediants by moving to chords a major or minor third above or below.

So, in D Major, potential chromatic mediants could include chords like F# Major (a major third above the tonic), Bm Major (a minor third below the tonic), or even chords derived from the parallel minor key such as E major. The key is that these chords contain notes not in the D Major scale.

It's important to distinguish chromatic mediants from their diatonic counterparts. If a mediant chord uses only notes within the key signature, it's simply a diatonic mediant, not a chromatic one. The presence of chromatic notes to the key is what makes it chromatic.

The interplay between tonal stability and chromaticism is what makes this interval of chords interesting. They create an unexpected harmonic effect, adding richness and depth to progressions.

They create moments of harmonic color without completely abandoning the tonal center. This keeps the listener engaged and adds a sophisticated touch. Chromatic mediants are frequently used in film scores, video game music, and other genres where a heightened sense of emotion and harmonic interest is desired. They contribute to a more colorful and expressive musical language.

The menacing sound of the "Imperial March" from Star Wars is partly due to its use of chromatic mediants, particularly the interval between a minor tonic and a minor chromatic mediant a third below.

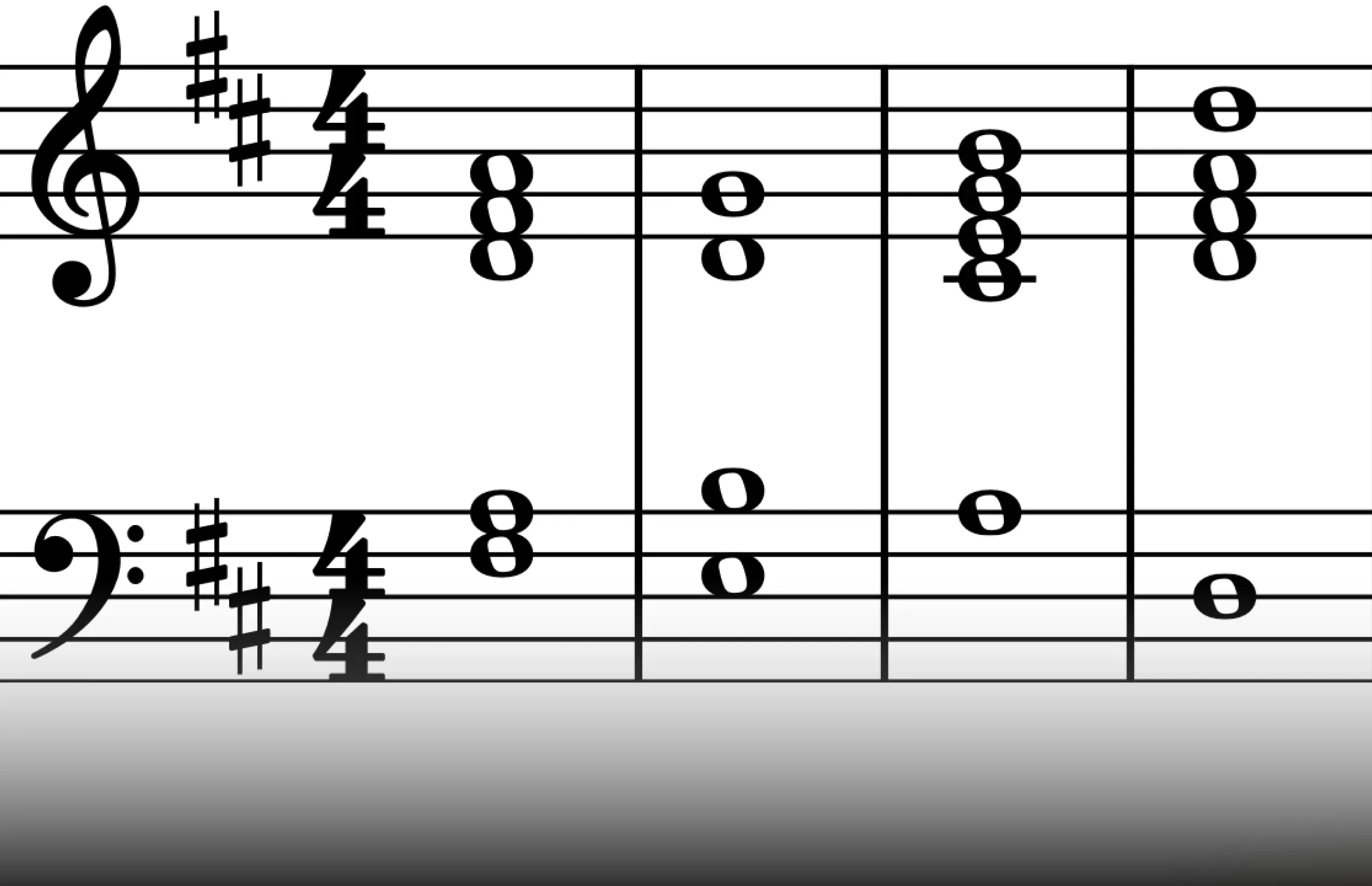

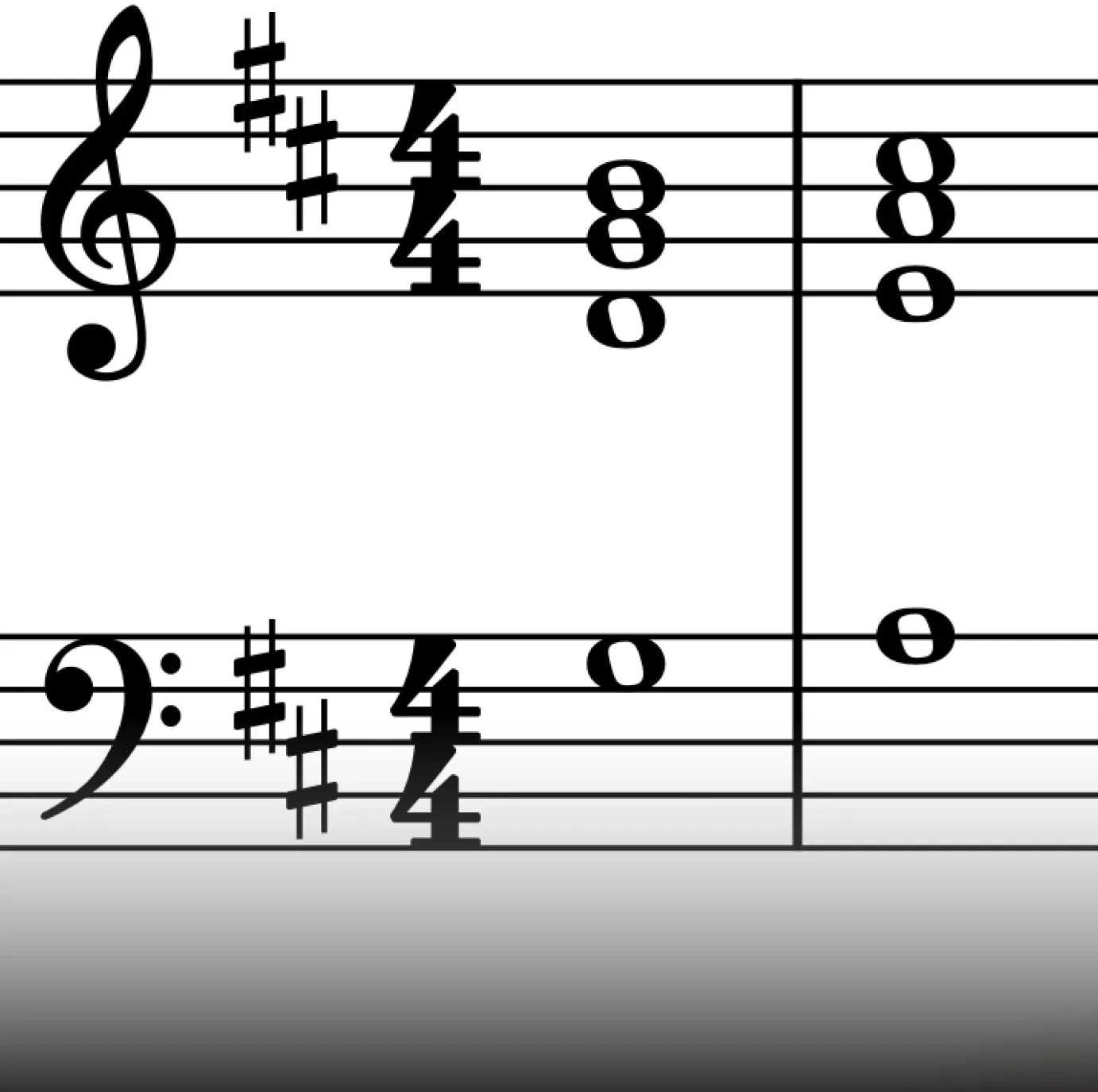

Here are two examples of two chromatic mediants in D Major.

Chords: D - F# - G - A7 - D

Below is a chord progression using the Tonic - Submediant interval.

Chords: D - B - G - A - D

Extended chords

Chord extensions add harmonic richness and complexity to your music. Triads, consisting of a root, third, and fifth, can be expanded by adding further thirds. Adding one-third creates a seventh chord; continuing this process gives us the 9th, 11th, and 13th chords.

Like seventh chords, these extended chords come in various types, including minor, major, and dominant, following similar naming conventions.

While extended chords might seem daunting at first, they're actually quite straightforward. The extension number corresponds to the scale degree above the root. A 9th, for example, is the 9th note of the scale above the root of the chord. Similarly, an 11th is the 11th, and a 13th is the 13th.

To avoid muddiness in larger extended chords like 11ths and 13ths, the 3rd and 5th are often omitted.

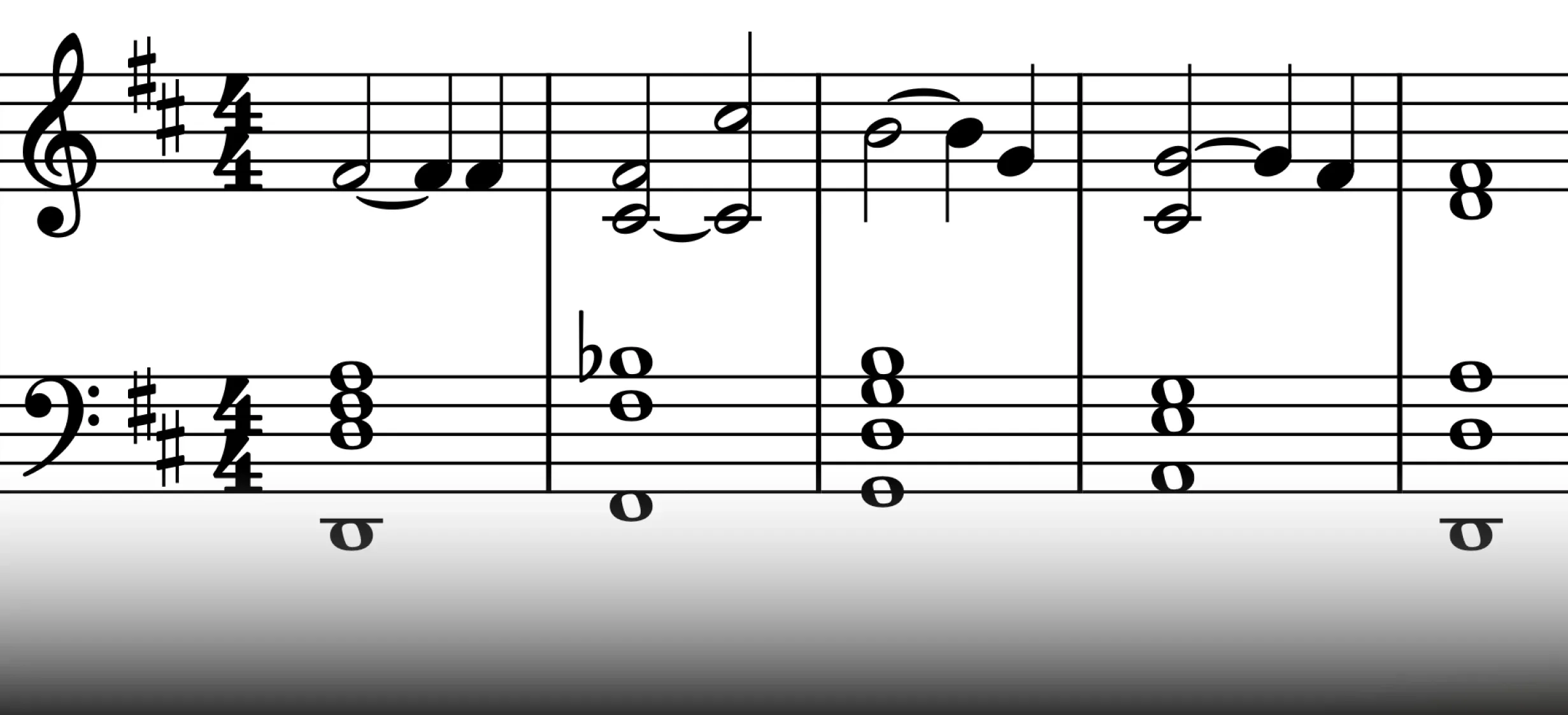

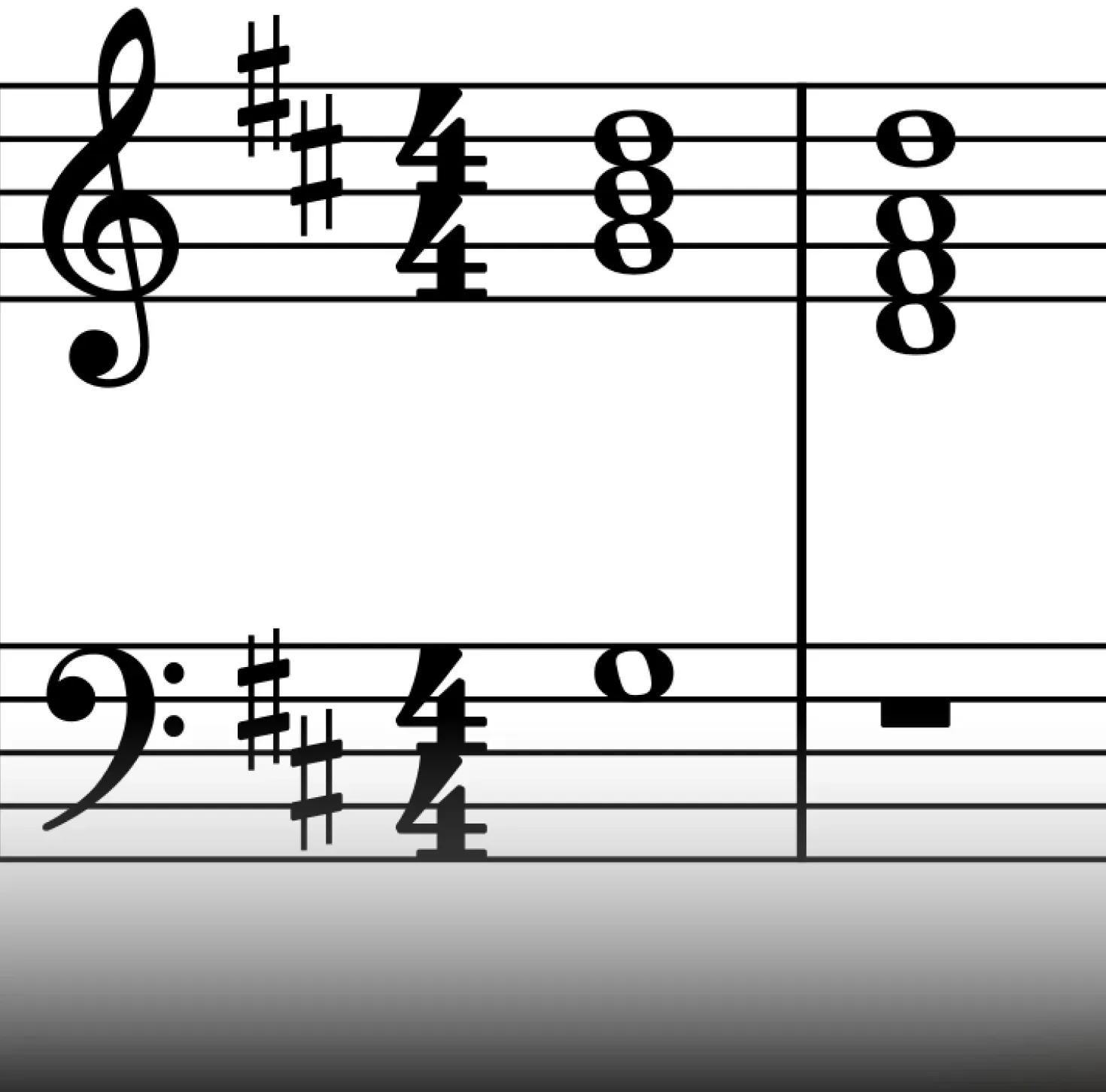

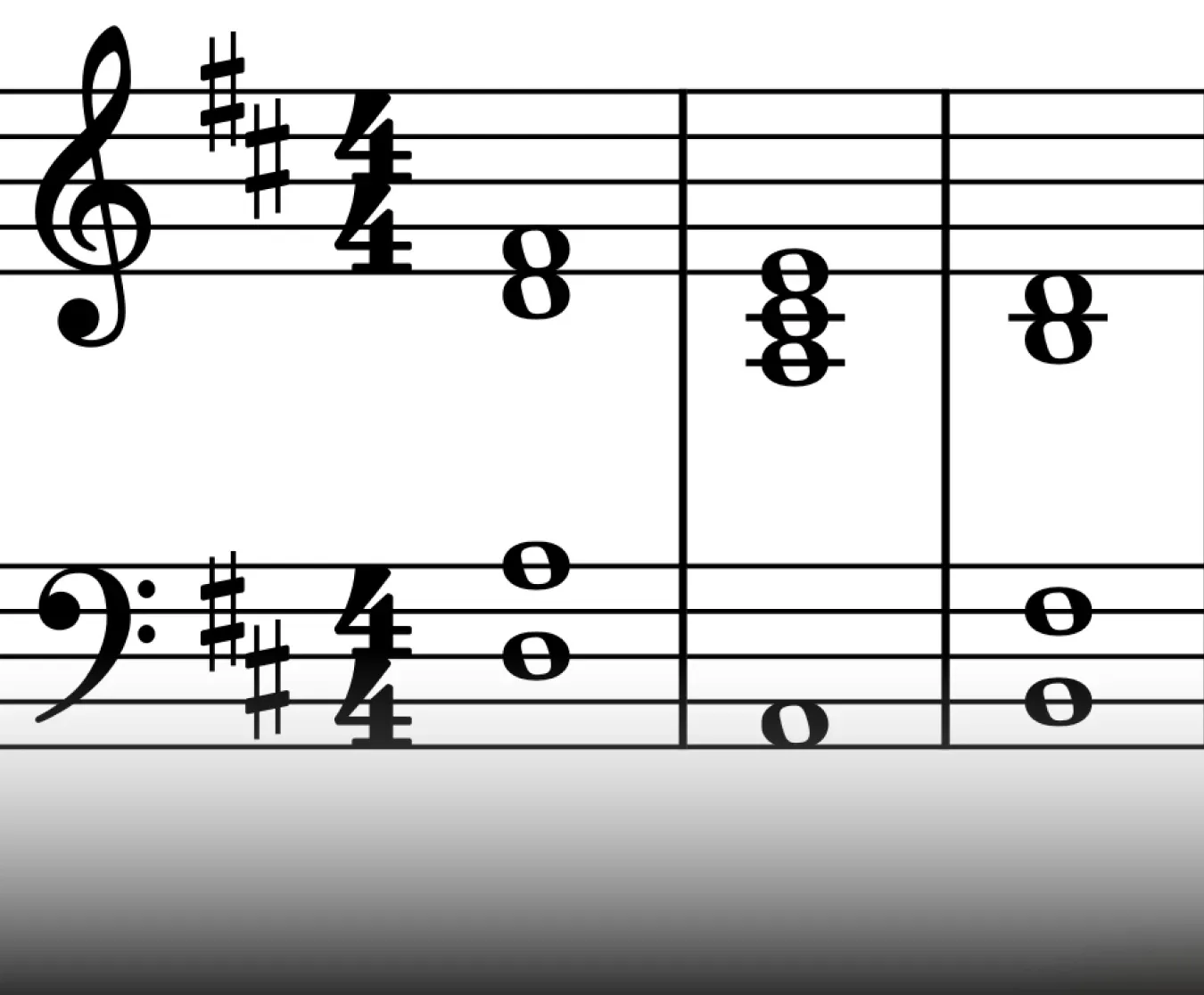

Here’s an A11 chord, with these two notes removed:

With this in mind, let’s look at chord extensions in D Major.

Ninth Chords

To build a 9th chord, we continue following the D major scale and add one more third on top of a seventh chord. This results in a more full-sounding chord compared to the triad and seventh chords.

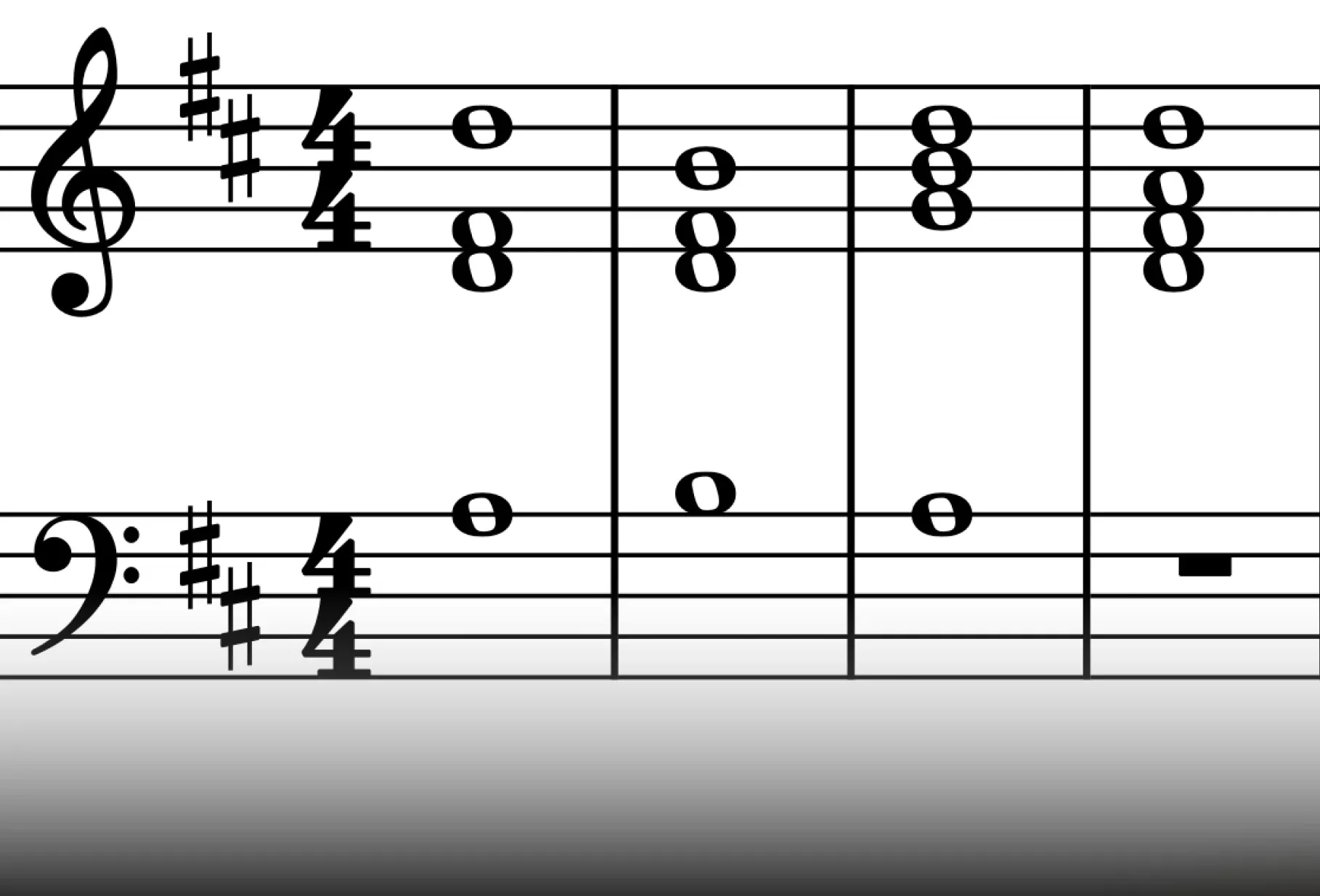

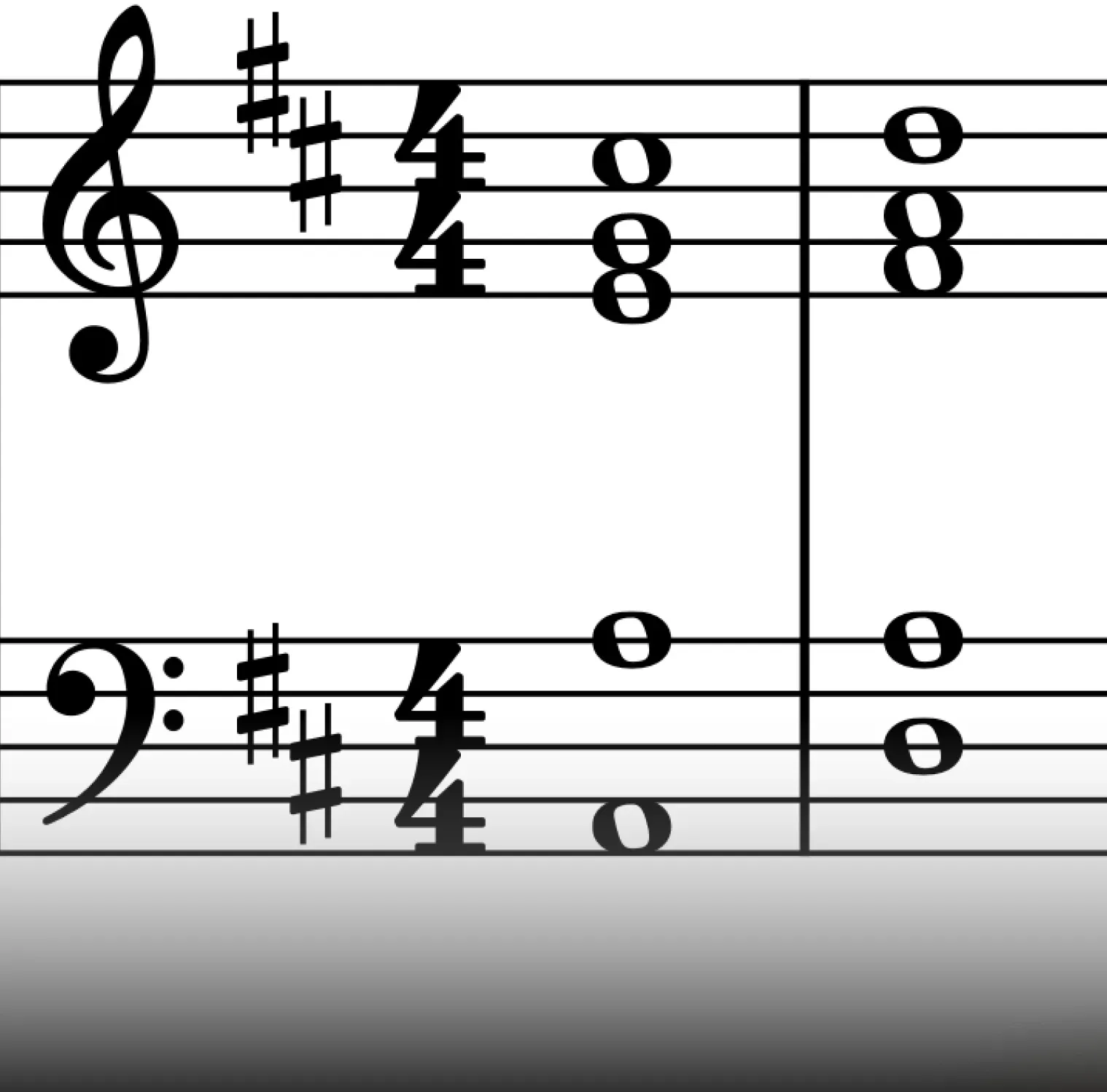

Let’s look at the Minor and Major 9th in a chord progression.

Chords: D/F# - Bm7 - Em9 - A

Another example using the Dominant 9th chord.

Chords: D - Em7 - A9 - D

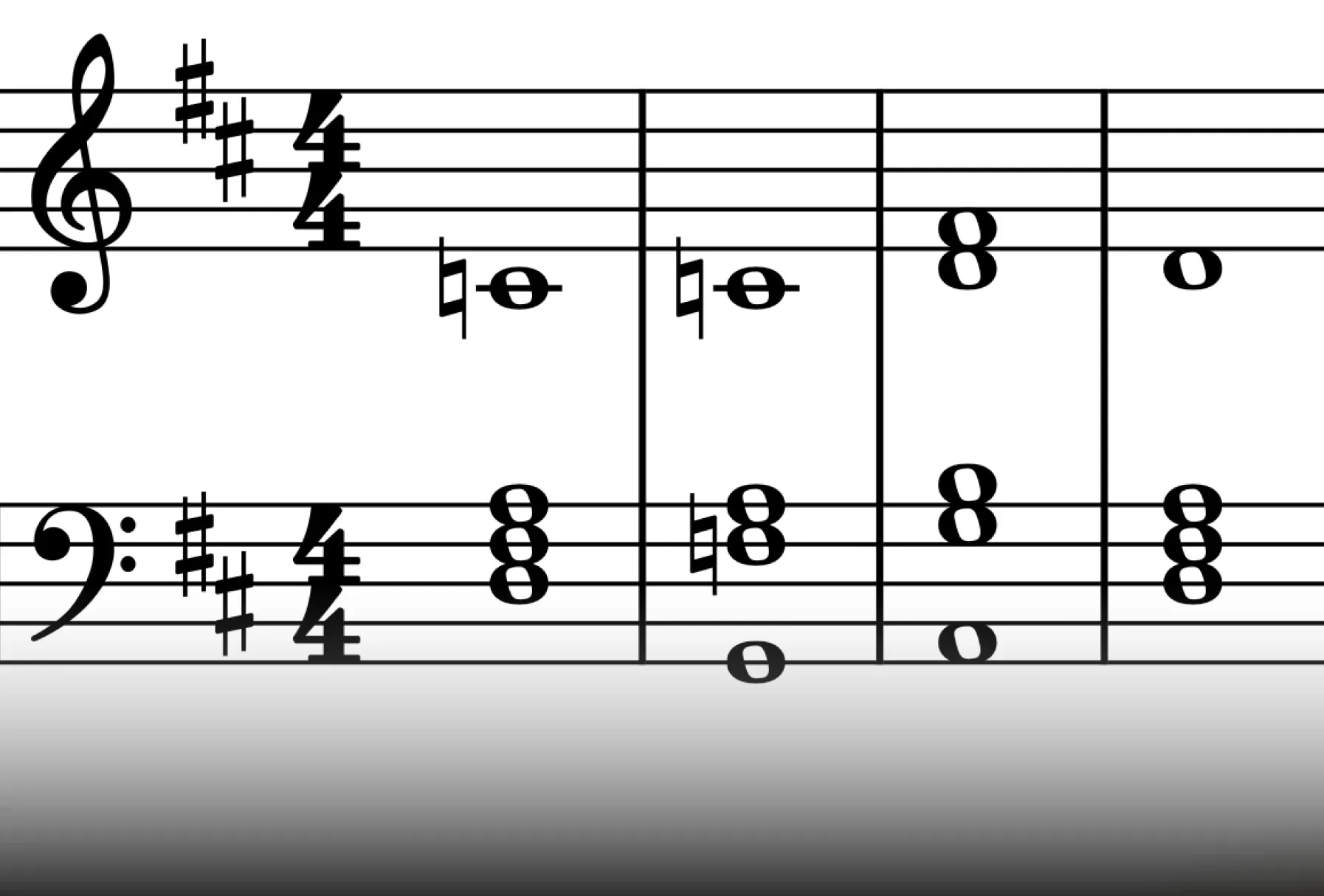

Eleven Chords

Adding another third above a 9th chord creates an 11th chord, a common sound in pop music, particularly when built on the fifth degree of the scale. Adele's"All I Ask"beautifully demonstrates the use of both secondary dominants and chord extensions, contributing to its rich harmonic texture.

Here, we’ve transposed it to D Major (originally in E Major).

Notice how the extended chord omits both the 3rd and the 5th, basically making it a G Major triad with A in the root.

Chords: D - B7 - D - B7 (V/ii7) - Em - A11 - A - D

Next is a simple chord progression using the A11 extension in the dominant position, where it’s mostly commonly found in pop and rock music.

Both the 3rd and 5th are omitted to provide clarity to the chord. This essentially results in a G Major triad with an added A in the root position.

Chords: D - Bm - A11 (or G/A) - D

Thirteenth Chords

The 13th chords, formed by adding yet another third, are harmonically rich and dense. Omitting the 3rd and 5th can create a warmer, more open sound.

Here we’ve done just that for the chords G11 and A13 chords. Reading it as F/G and A13 makes it easier and can be less confusing than looking at a large 7-note chord.

Chords: D7 - G11 (or F/G) - A13 (or G7/A) - D

Chord extensions are a staple of jazz music, but have a place in pop and rock music too. Artists like Muse and Jimi Hendrix, among many others, use them in many songs to add an extra layer of depth and interest to their harmonies.

What’s the Difference Between “D9” and “Dadd9”?

Sometimes we want the color of a chord extension without the density. That's where"add"chords come in. For chords like Dadd9, Aadd11, Bmadd13, and so on, simply add the 9th, 11th, or 13th degree to the triad, while omitting the other extensions. In contrast, a D9, D11, or Dmaj13 implies all the notes up to and including the named extension.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

We've already touched on using chromatic notes through diminished and augmented chords. Exploring notes outside the diatonic scale is a fantastic way to add unexpected twists and turns to your music, creating more engaging chord progressions.

Experimenting with chromatic chords, passing tones, parallel harmonies, and chromatic mediants can be a great source of inspiration and a helpful tool when you're facing writer's block, as they offer more unusual harmonic colors.

We’ve already briefly looked at using chromatic notes by using diminished and augmented chords in your chord progressions.

Relative Minor: B Minor

Every major key has a parallel minor, and every minor key has a parallel major. These key pairs share the same key signature but have different tonal centers and harmonic functions.

While both keys use the same notes, the tonal center -D or B - determines the harmonic function of each chord. Establishing either D or B as the "home" note fundamentally changes how the chords within that collection of notes are perceived and used.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

Modulating to B minor, the relative minor of D Major opens up a new tonal landscape with seven distinct diatonic chord functions - all within the same key signature. For a deeper exploration of B minor chords, see"Chords in B Major: A Comprehensive Guide".

The close relationship between these keys allows for exciting harmonic interplay. This shift in tonal center adds depth and creates contrasting emotional textures for different sections of the song.

Modulation between relative keys is a common compositional technique, allowing you to, for example, evoke a more melancholic mood by moving to B minor and then returning to D Major for a more uplifting feel.

A simple modulation technique involves identifying the function of a chord in the new key. For example, in D Major, an I-IV progression (D - G) can be a springboard to B minor. The IV chord (G Major) in D Major becomes the submediant (VI) in B minor. From this point, you can pivot to the dominant 7th of B minor (F#7) and then resolve to B minor, creating a classic V7-i progression in the new key.

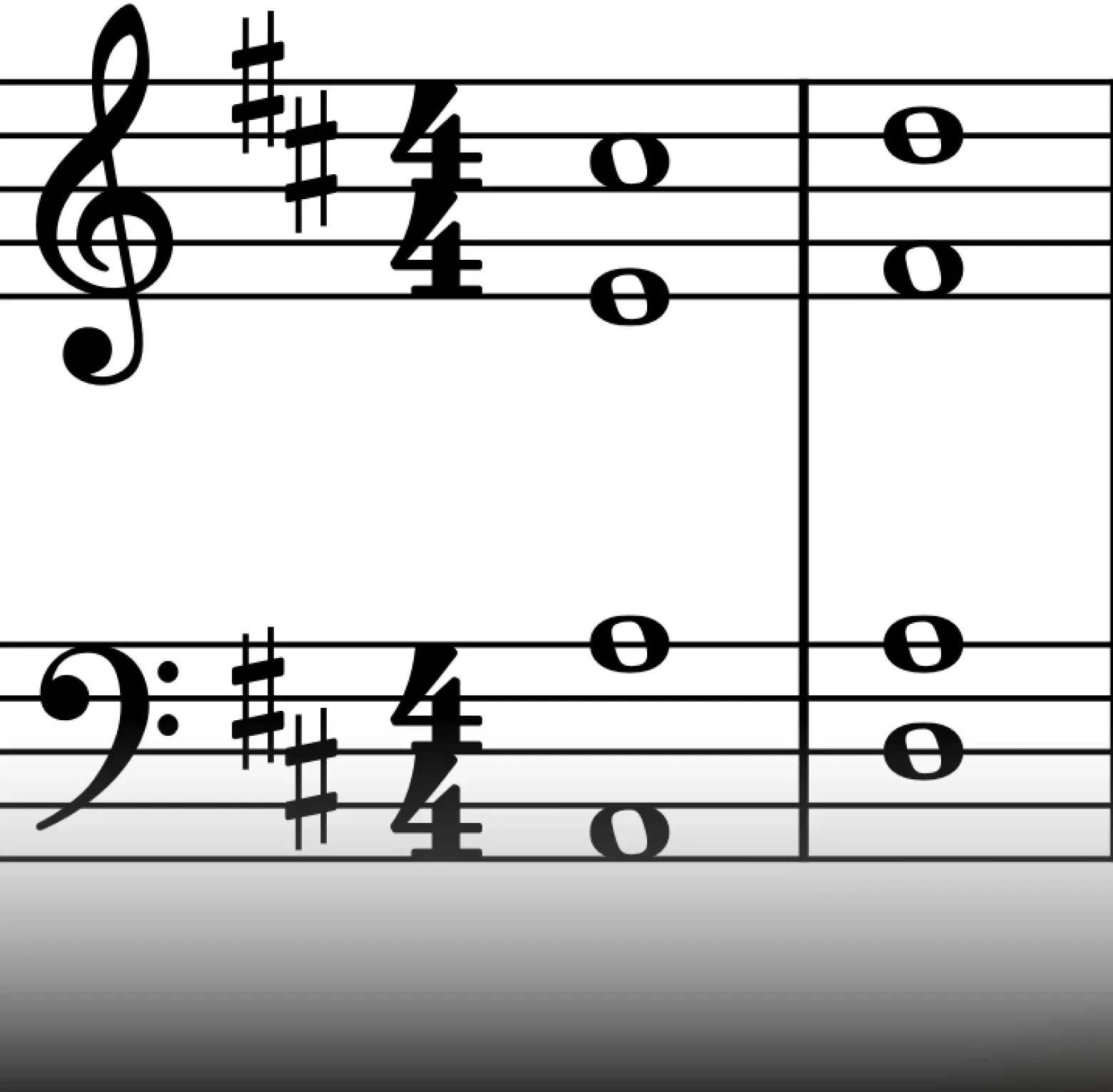

Here’s an example of this modulation to the relative minor key, B minor:

Chords: I (D) - IV (G) - V/vi (F#7) - (vi) Bm - (I) Bm - (iv) Em - (III) D -(V7) F#7 - (I)Bm

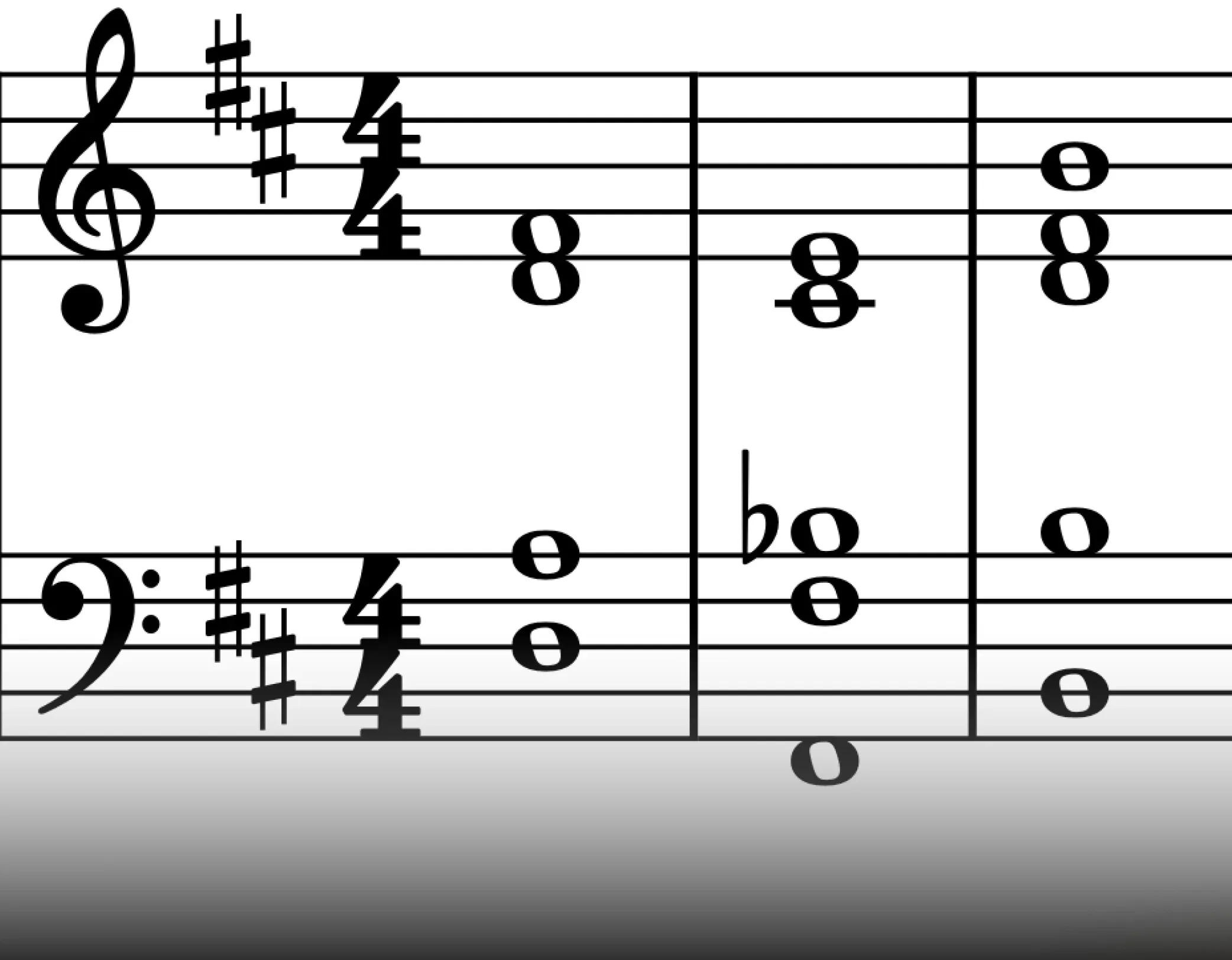

Parallel Chords

Parallel chords, formed by altering a chord's quality with accidentals, introduce unexpected harmonic twists. For instance, in a D Major progression, changing the subdominant (G Major) to G minor (by lowering the B to Bb) creates a distinct emotional shift.

This technique can surprise the listener and alter the song's mood. A common application is using the parallel tonic - D minor in the key of D Major - to create a melancholic and surprising effect.

However, parallel chords should be used with caution. Overuse can disrupt the music's harmonic stability and create a lack of focus. Strategic placement emphasizes key moments and enhances the overall tonal richness of a song.

Cadences in D Major chord progressions

Just as punctuation marks structure and emphasizes language, cadences serve a similar function in music. They are the musical equivalent of punctuation, shaping the emotional impact of a musical phrase. By varying cadences, producers and composers can create a wide range of musical expressions, from powerful climaxes to soft and gentle endings.

Below, we'll explore common cadences in D major.

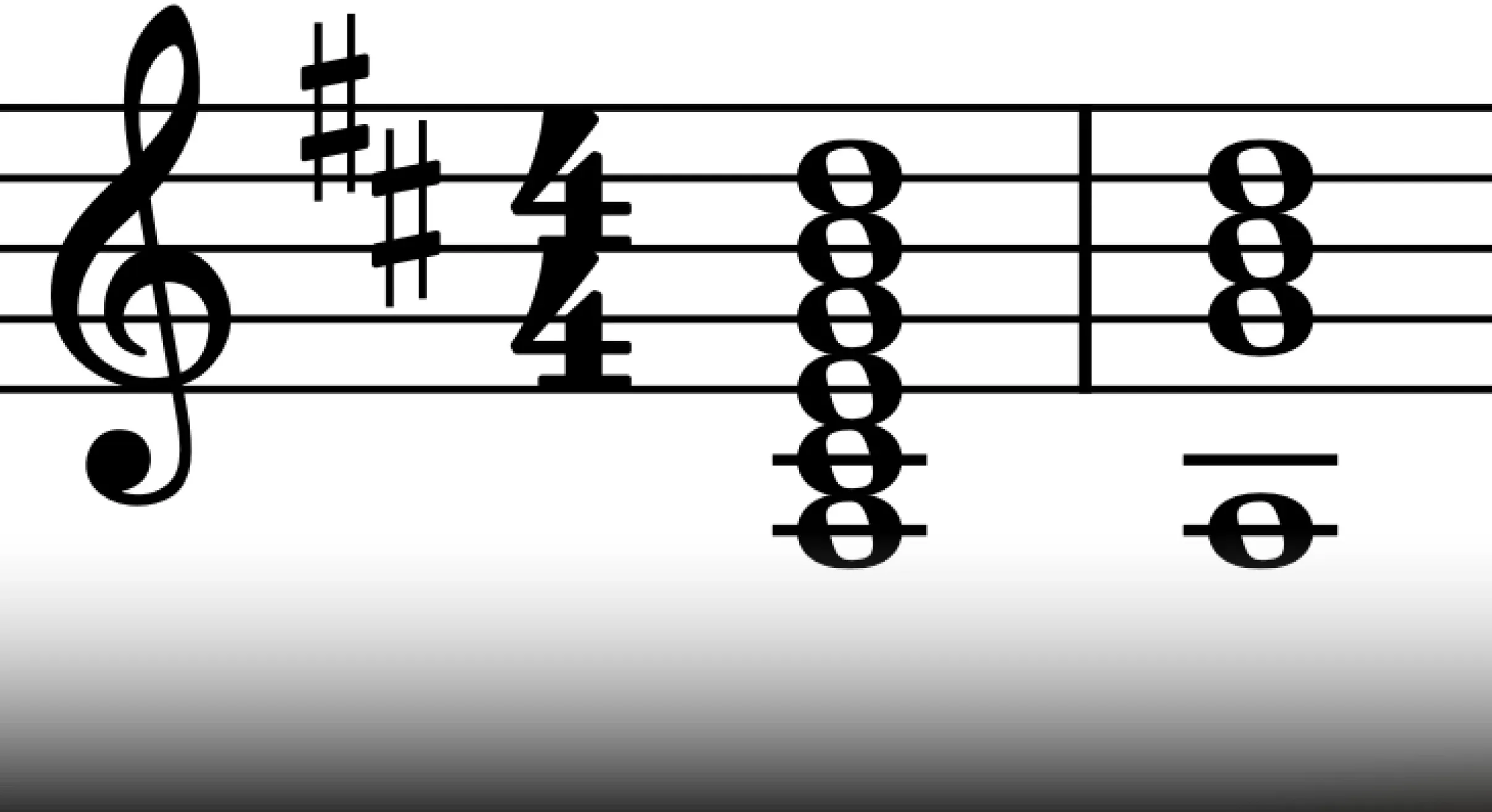

Perfect Cadence

The classic V-I cadence provides a strong, familiar sense of resolution, effectively concluding a piece of music. This clear and decisive ending creates a feeling of musical closure.

Two requirements for the perfect cadence is that both chords are in root position, meaning the root of each chord is the lowest note. And the highest voice of the tonic chord must also be the root of the chord. This ensures the strongest possible resolution.

Dominant → Tonic (V - I)

A Major → D Major

For an even more powerful resolution, a dominant seventh chord can be used to resolve the tonic.

A7 → D Major (V7 - I)

Plagal Cadence

The plagal cadence, or"Amen Cadence,"offers a gentler conclusion than the perfect cadence. Its softer quality makes it a frequent choice for traditional hymns, often used to close with the IV-I progression on the word"Amen”.

Subdominant → Tonic (IV - I)

G Major → D Major

Half Cadence

A half cadence concludes the phrase on the dominant chord. Unlike the perfect and plagal cadences, which provide a sense of finality, the dominant chord creates a feeling of instability, leaving the musical phrase unresolved.

Ending a phrase on the dominant chord is a powerful way to create anticipation and build energy. The subsequent tonic resolution at the beginning of the next section then provides a sense of forward momentum. This strategic use of the half cadence adds dynamic and emotional depth to the musical journey.

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (I / ii / IV → V)

D Major→ A Major

E Minor → A Major

G Major→ A Major

Interrupted Cadence

The interrupted cadence begins as if it will resolve strongly and definitively, but then unexpectedly lands on the submediant chord. This cadence can create a smooth transition to a new tonal center, particularly if the music modulates to the relative minor key.

Dominant to Submediant (V - vi) - A Major → B Minor

Aim for Stability In Your D Major Chord Progression

This article has demonstrated the wealth of possibilities within diatonic harmony. Even using just the seven diatonic triads and their inversions can create compelling progressions. While harmony can be complex, it doesn't have to be. Stability is often key, and a foundation of diatonic chords, punctuated by diminished, augmented, or extended chords, is a good approach.

Traditional theory categorizes diatonic chords as primary and secondary. The primary chords I (D Major), IV (G Major), and V (A Major) - provide the harmonic bedrock, creating a balance of tension, anticipation, and resolution.

The secondary chords - ii (E minor), iii (F# minor), vi (B minor), and vii° (C# diminished) - offer contrasting moods and add complexity and color. Analyzing song structures reveals a frequent emphasis on primary chords, with secondary chords used strategically for flavor.

Extended chords and accidentals should be used purposefully to maintain harmonic stability and avoid disorientation.

Musiversal: For Musicians, by Musicians

Take your music to the next level by recording your songs with professional musicians. With Musiversal you have access to 80+ artists and engineers just one click away. Our Unlimited subscription gives you unlimited recording sessions with top-tier talent.

Find the right instrument or artists you need for your music. Join your recording session live via link, collaborate with the artists in real-time, and ensure your creative and musical vision is met. At Musiversal you’ll find anything from drums, cello, guitar, strings, piano, winds, bass, beat makers, songwriters, and much more.

Book a session with the artist of your choice at a time that works best for you, and experience your music coming to life in real-time.

If you have just a spark of an idea, our songwriting sessions offer songwriting collaboration to help you develop it into a full song - or refine and complete one you’ve already started.

Do you have completed songs that need professional mixing and mastering? Schedule a session with an engineer and ensure it sounds polished and release-ready.

For more tips and advice on music theory, songwriting, creativity, music, production, gear, marketing, distribution, keep an eye out for the Musiversal Blog. We updated it weekly. Subscribe to our newsletter and receive notifications on our exclusive Musiversal discounts, gain insights from inspiring session highlights, get helpful marketing advice, and much more!

[CTA:community]

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist