Learn Chords in B Minor: Functions, Tips, and Examples for Beginners

Discover how to learn D Major chords, their role in music theory, and how to use them in your own compositions. Perfect guide for beginners and musicians

Introduction

Understanding which chords are available in any key – and why they work – is essential for musicians and producers alike. This knowledge not only simplifies the songwriting process but also helps you write music with greater intention and creativity.

In this guide, we'll break down the chords in B minor, starting with an overview of the B minor scale before exploring the triads built within the key. We'll then examine non-diatonic chords including types of augmented, diminished, and suspended chords to expand your harmonic palette.

By the end of this guide, you'll have a solid foundation in the B Minor key, allowing you to create music with more depth, intrigue, and movement.

Here’s what you’ll learn:

This article provides a step-by-step guide to the chords in B minor, explaining their functions and how to create compelling progressions to enhance your sound.

The Basics of B Minor

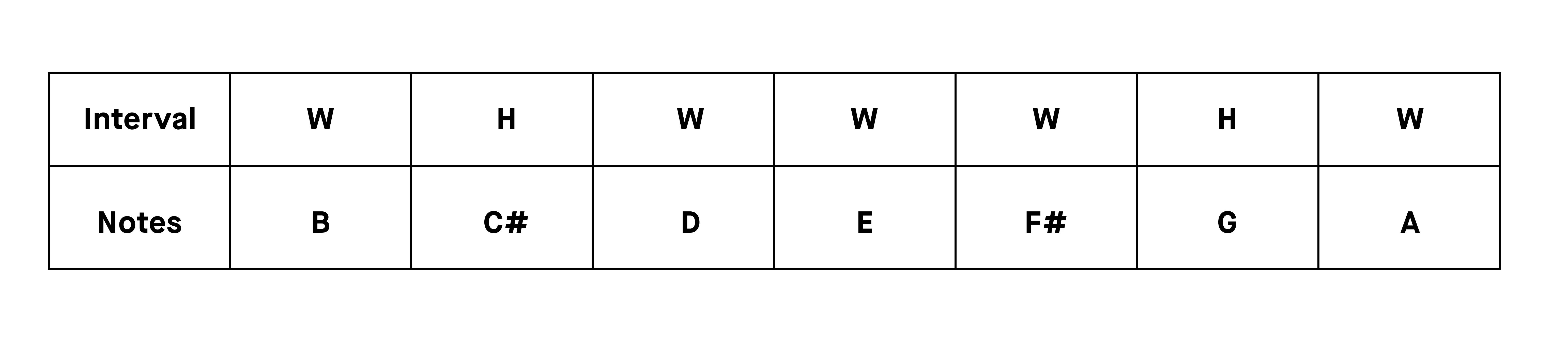

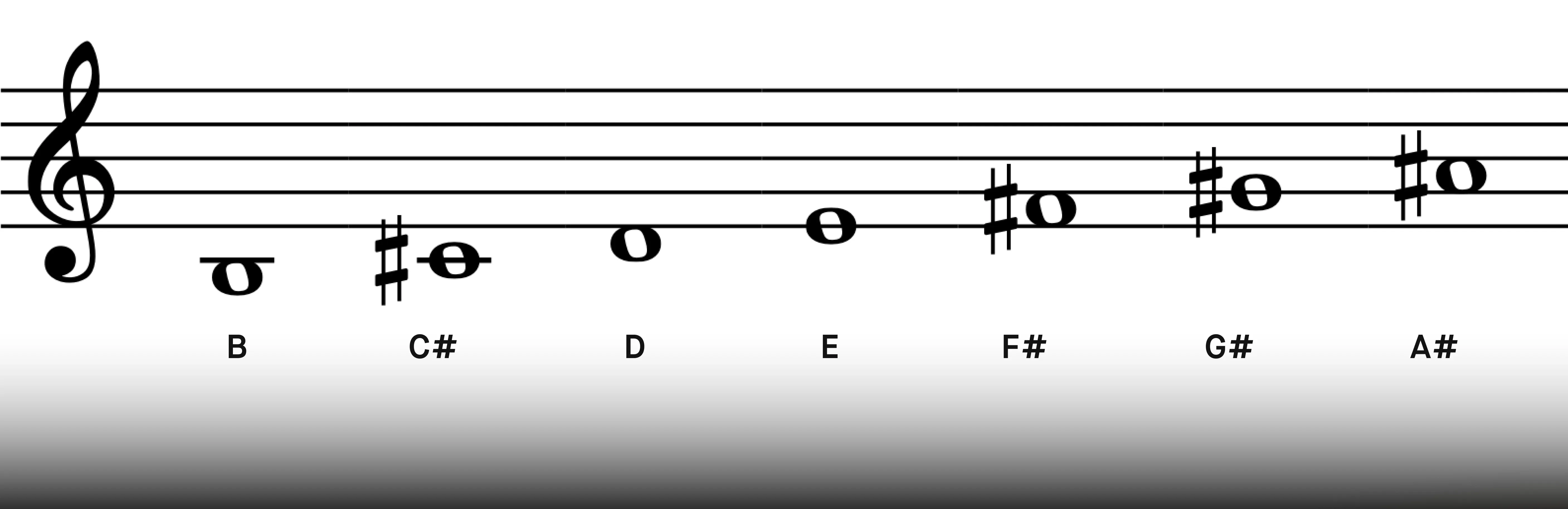

The B minor scale, comprised of seven notes (B, C#, D, E, F#, G, A), forms the foundation for B minor chords and progressions. These diatonic notes are derived from a specific pattern of whole and half steps, creating the characteristic sound of the B minor scale.

This exact pattern of whole steps and half steps makes up the Aeolian mode – also simply known as the natural minor scale. (For a clear and engaging explanation of music modes, check out Charles Cornell's video ).

Each note occupies a specific position within the scale that tells us how it relates to the tonic (the foundation of the key), which helps determine its harmonic function. The chords for B Minor scale are built on each of these scale degrees.

In B Minor, we can build chords using the following notes:

- B - Tonic (1st degree) - i

- C# - Supertonic (2nd degree) - ii° (diminished chord)

- D - Mediant (3rd degree) - III

- E - Subdominant (4th degree) - iv

- F# - Dominant (5th degree) - v / V

- G - Submediant (6th degree) - VI

- A - Subtonic (7th degree) - VII

Each note occupies a specific position within the scale, called a scale degree, which tells us how it relates to the tonic and helps determine its harmonic function and color.

Our blog features in-depth music theory tutorials covering all key signatures. Check it out to deepen your understanding of music.

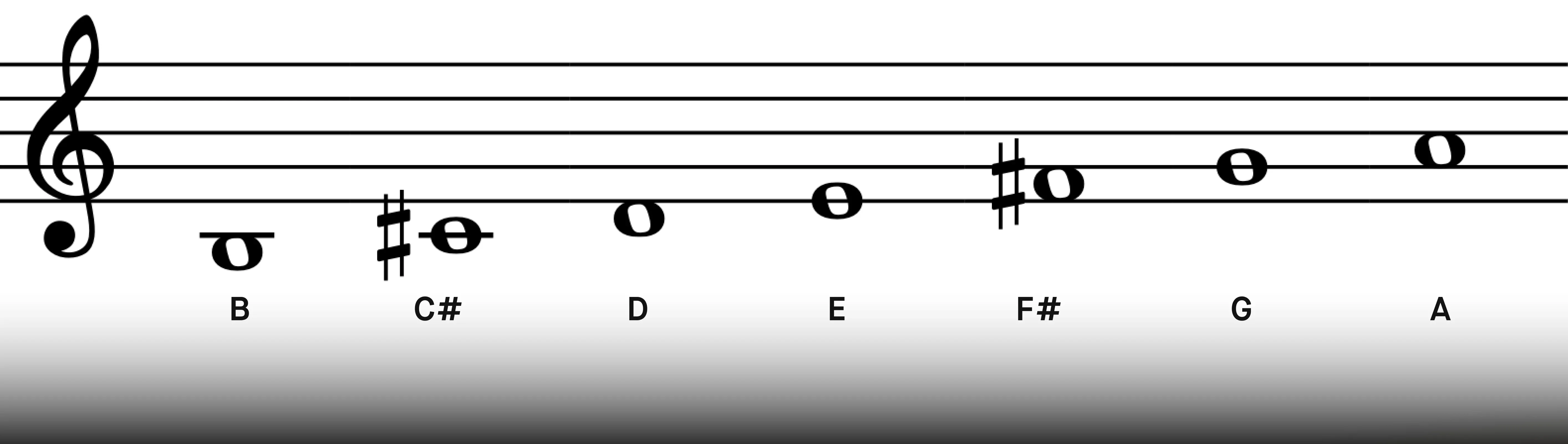

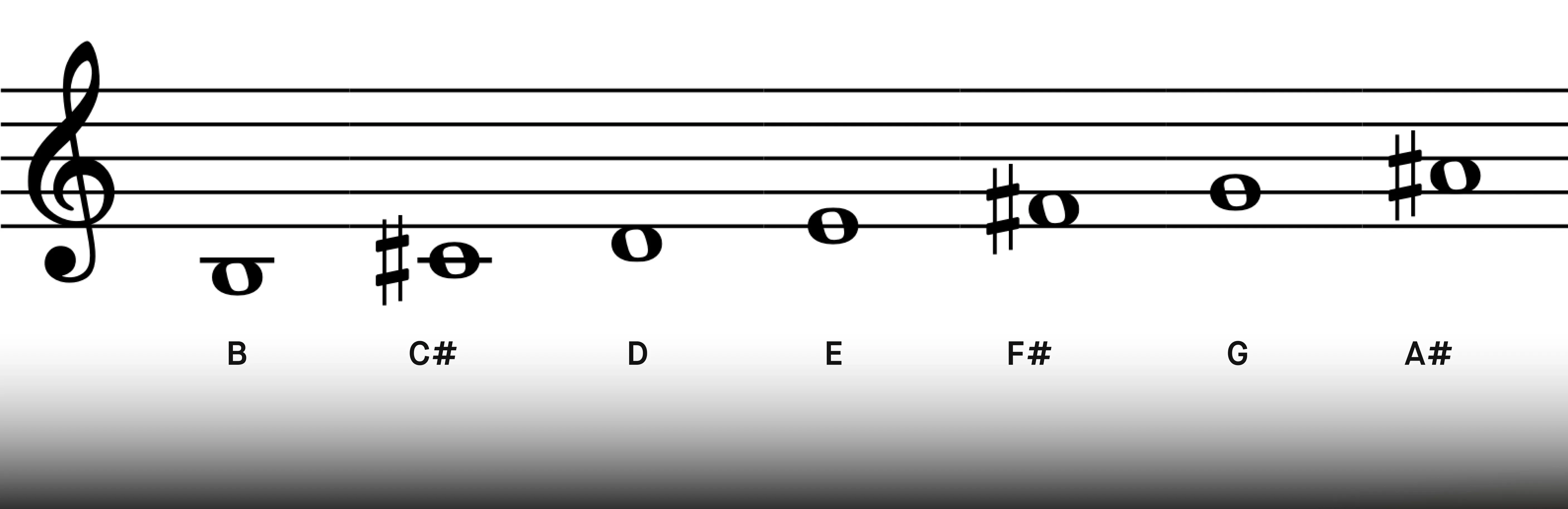

Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor

By making small adjustments to the intervals of the natural minor scale, we access two more minor scales: The Harmonic minor and Melodic minor.

These two minor scales offer distinct flavors and harmonic possibilities. The harmonic minor, for instance, adds a dramatic, almost exotic quality, while the melodic minor offers a smoother, more lyrical feel.

The harmonic minor is closely related to the natural minor, but with one crucial difference: the seventh degree is raised by a half step, creating a leading tone, which strongly pulls towards the tonic and enhances the sense of resolution.

The raised seventh degree in the harmonic minor mode is often used in progressions even when the overall scale context is the natural minor, as it allows for the creation of a major dominant chord providing the strong V-i resolution.

The melodic minor's ascending form differs from the natural minor by raising both the sixth and seventh degrees. This is traditionally explained as a way to create smoother voice leading towards the tonic. However, in its descending form, it reverts to the natural minor scale for a stronger sense of tonal closure.

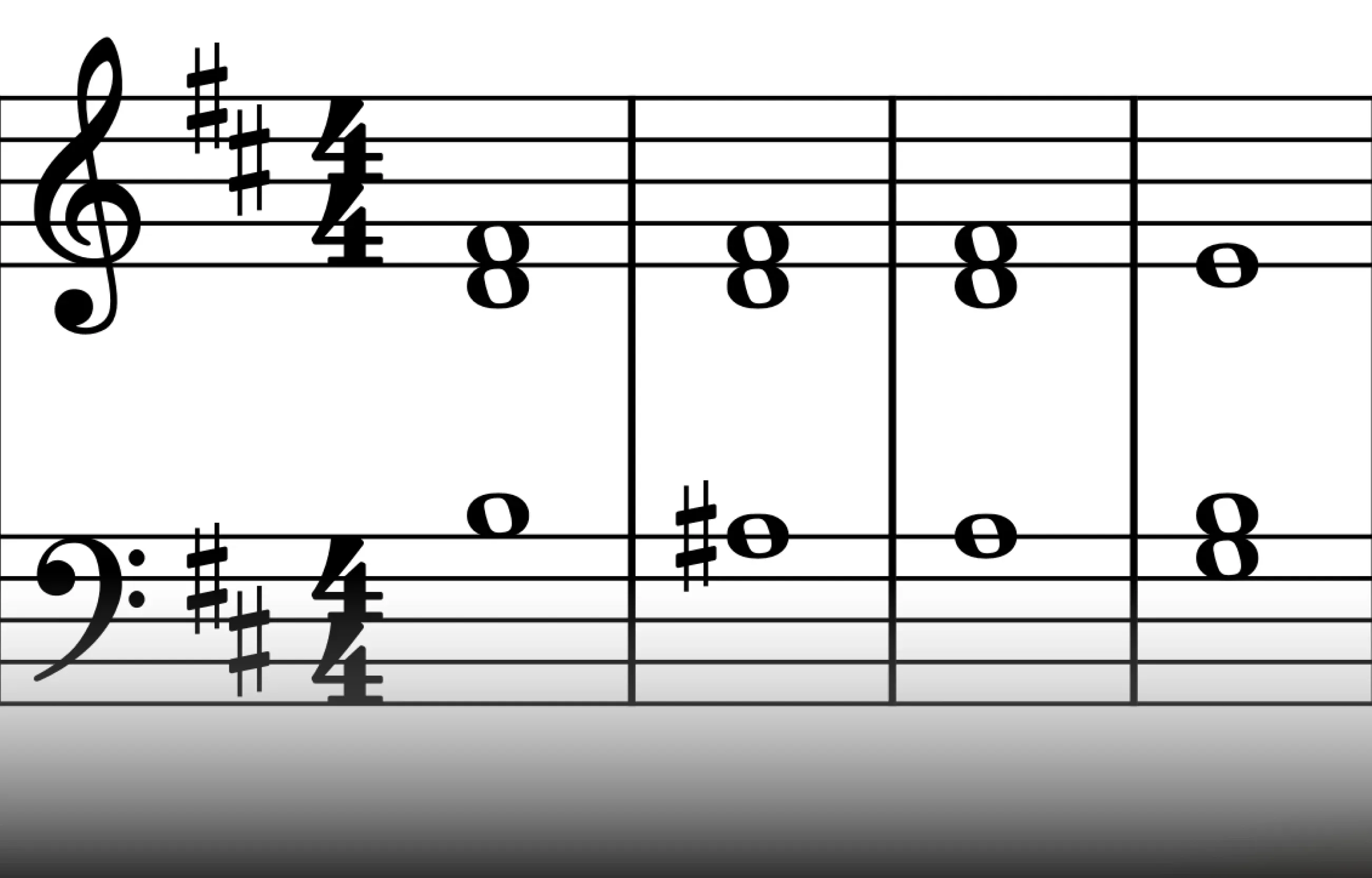

Harmonic Minor

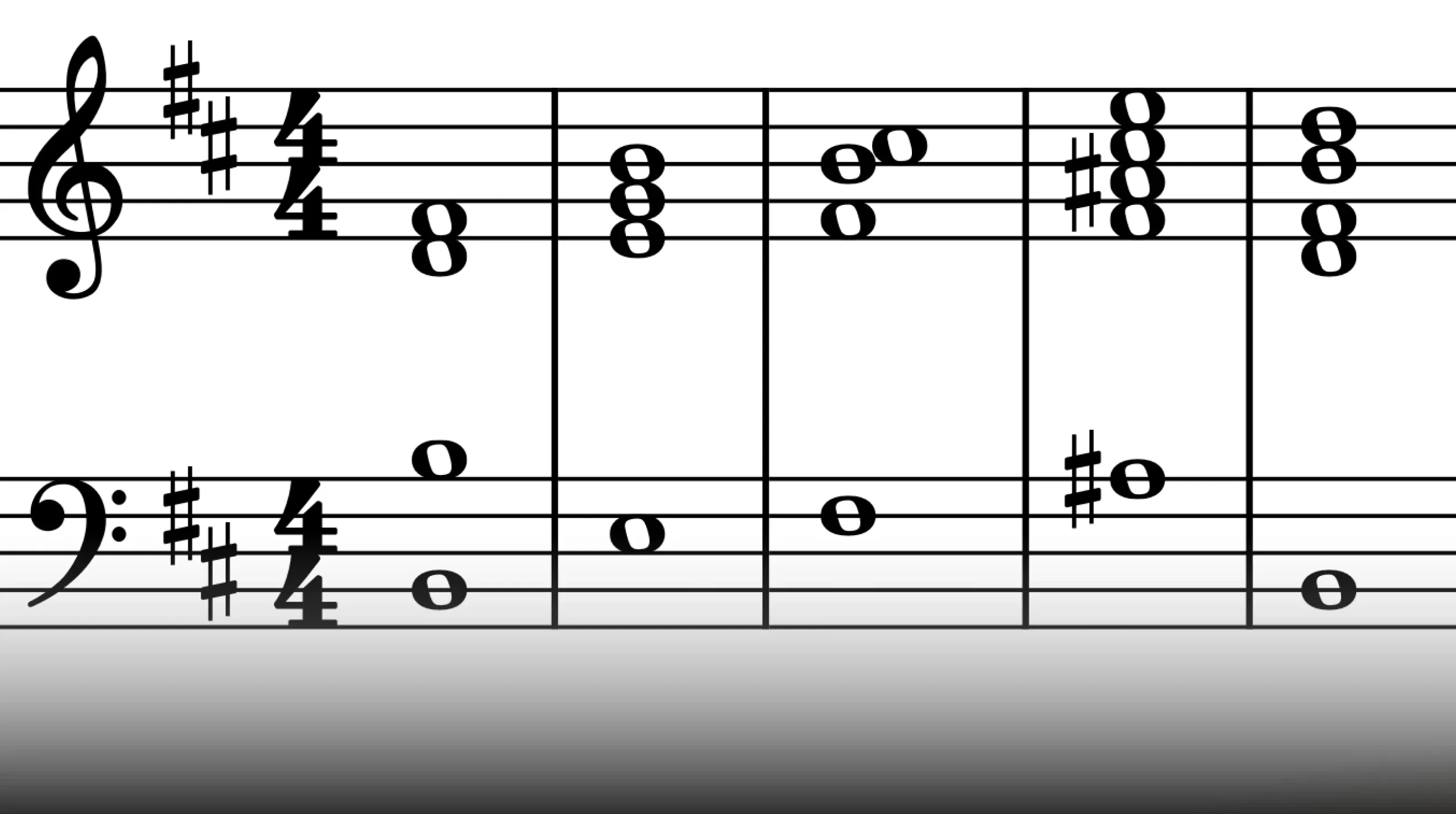

Melodic Minor

B Minor Chords and Their Functions in Music

Chords in B minor are constructed using the fundamental principles of tertian harmony (based on intervals of thirds). The most common chord type, the triad, consists of three notes stacked in intervals of thirds:

- Tonic (Root): The foundational note that gives the chord its name.

- Third: The interval of the third determines whether the chord is major or minor. A major third above the root creates a major chord, while a minor third above the root creates a minor chord.

- Fifth: Adds depth and harmonic stability.

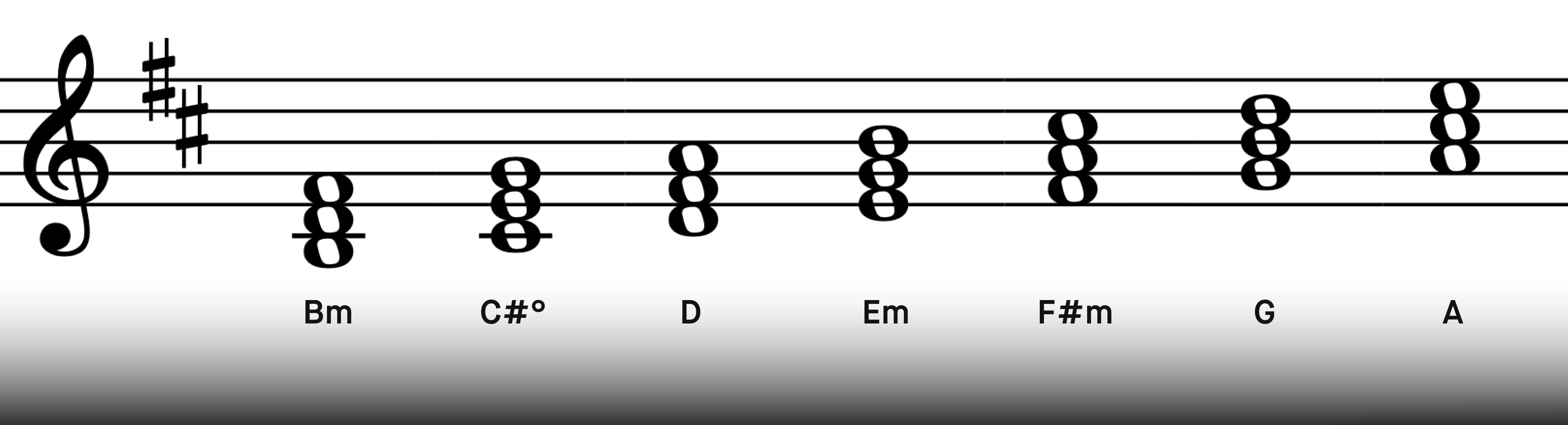

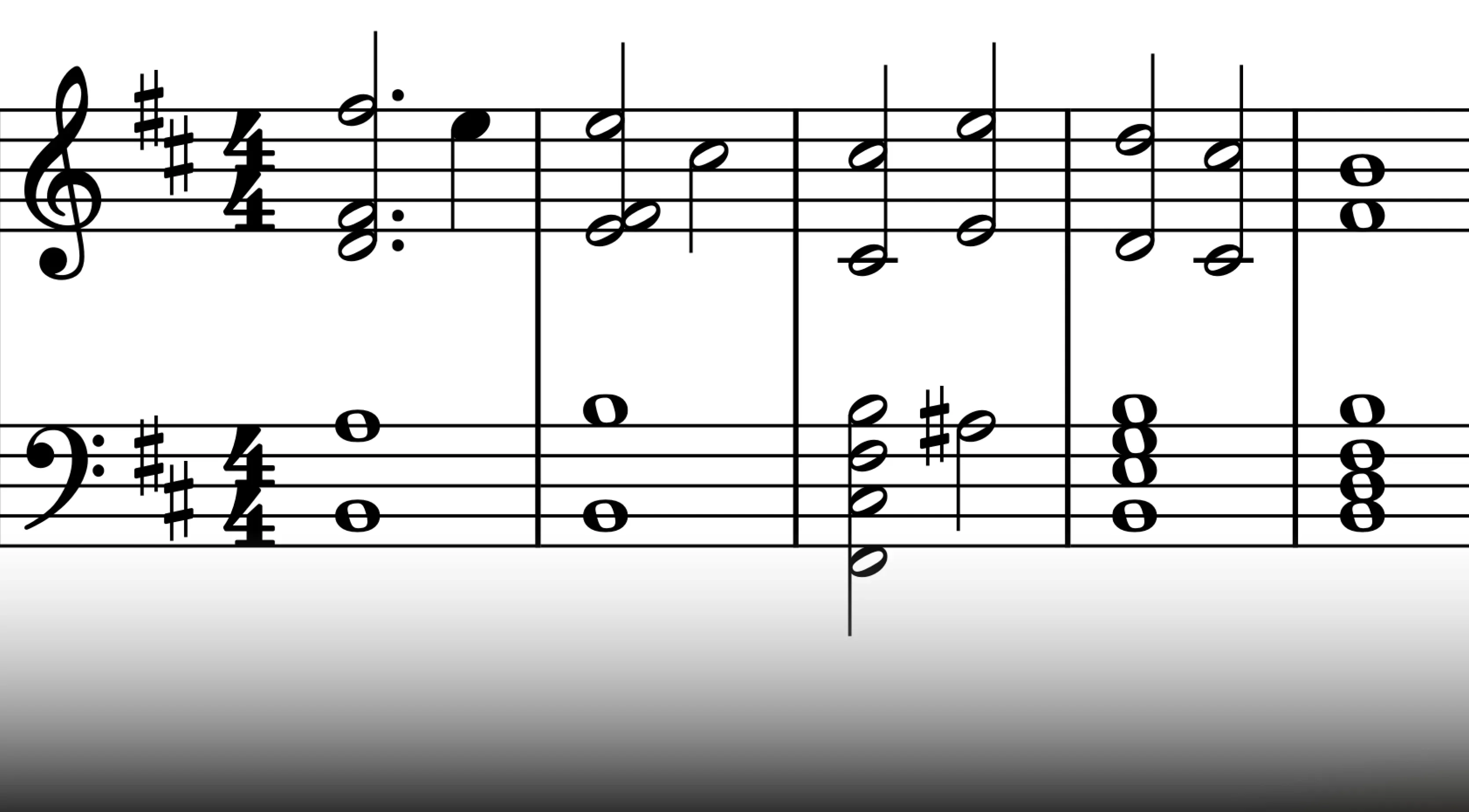

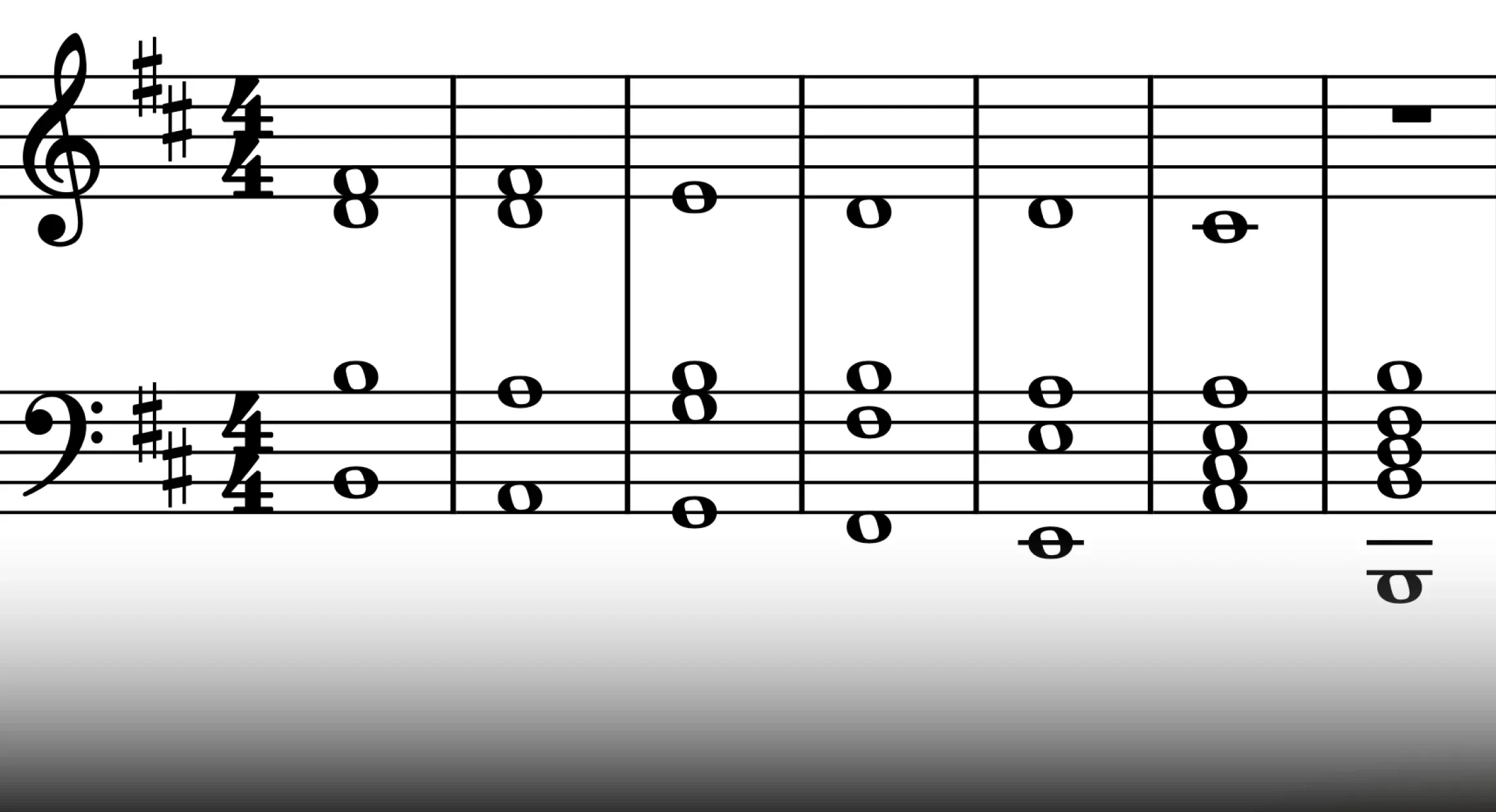

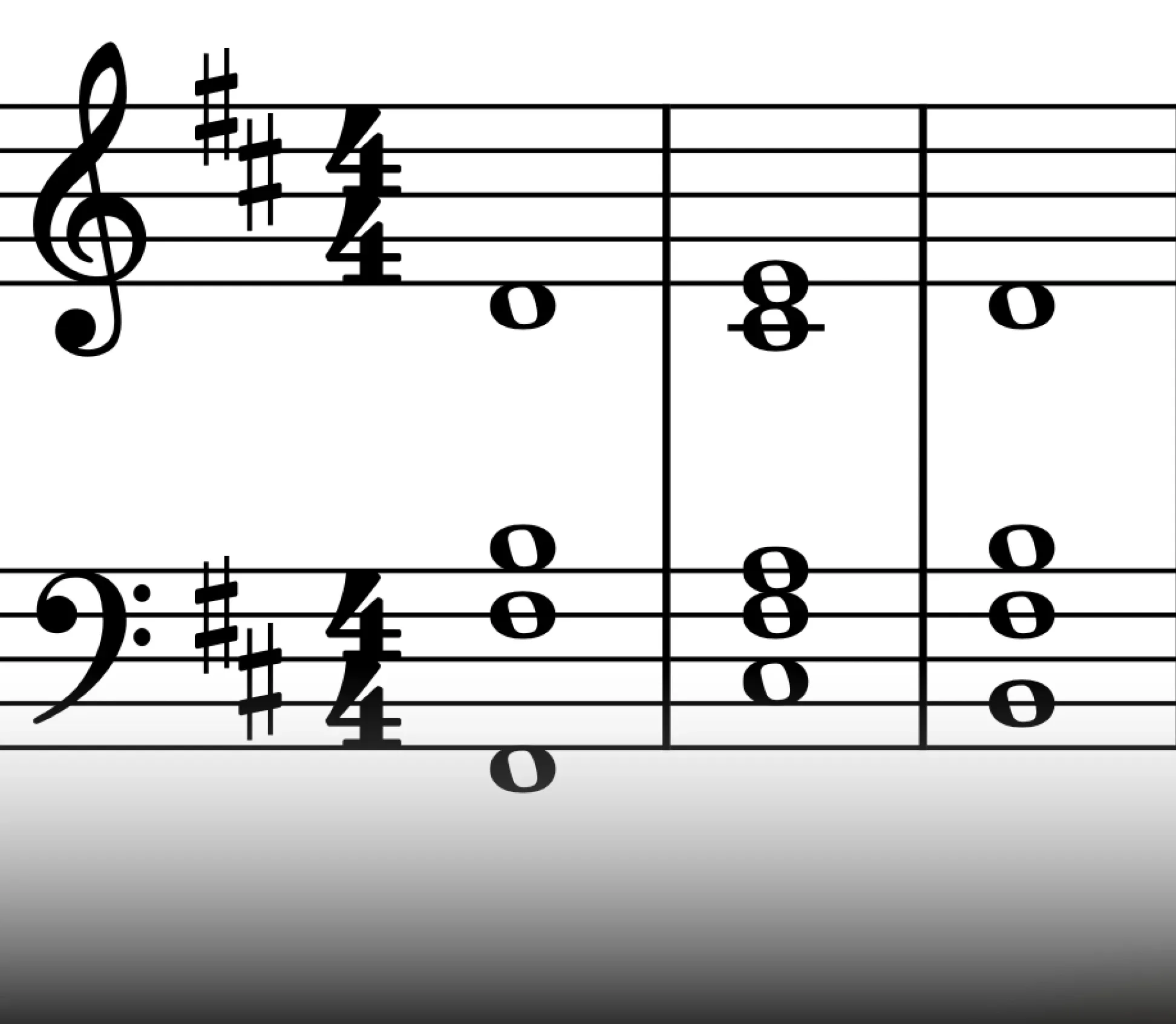

There are seven diatonic chords in B Minor, each built from the notes of the B Minor scale. In this section, we’ll explore these chords and how they function within a musical context, along with common ways to use them in songwriting and harmonic progressions.

The chords in B Minor are B Minor, C#°, D Major, E Minor, F# Minor, G Major and A Major.

The chords in B Minor are B Minor, C#°, D Major, E Minor, F# Minor, G Major and A Major

This section explores B minor piano chords, their functions, and common uses within song progressions. The piano's visual layout simplifies chord construction and the identification of alterations, like those in augmented chords.

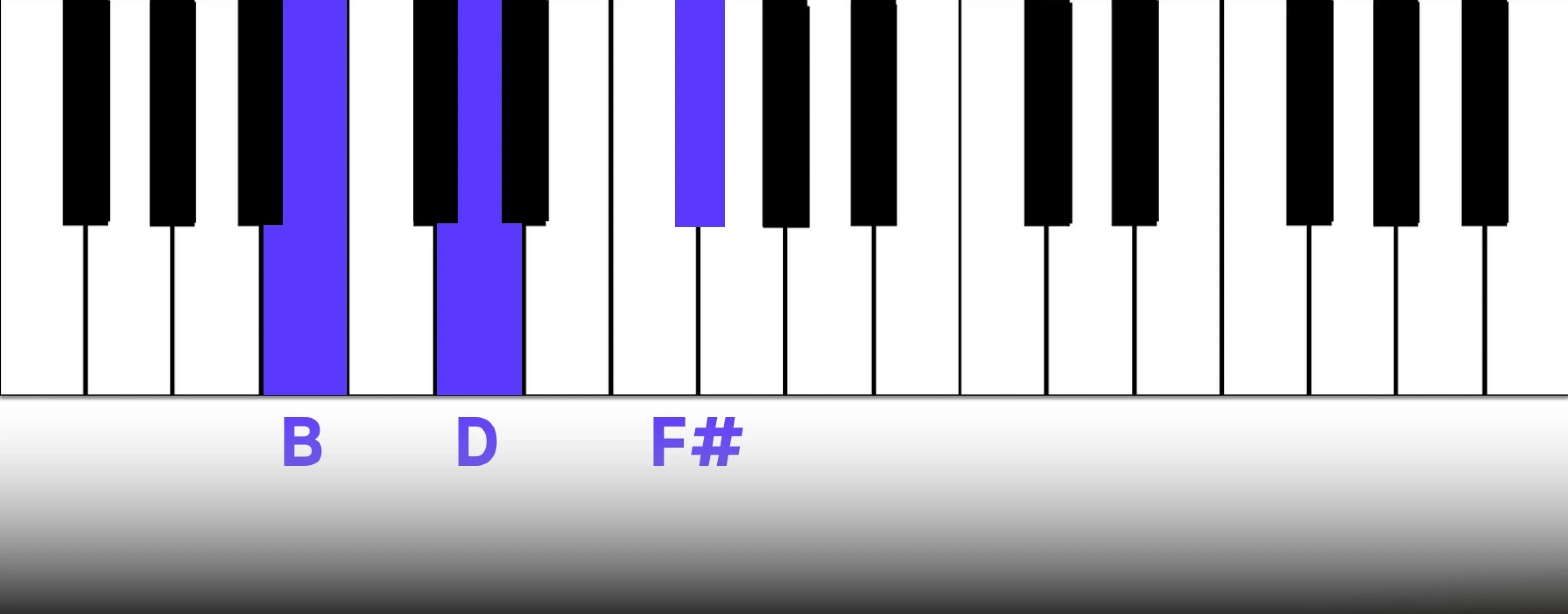

i: B Minor

The B Minor chord serves as the tonic, acting as the foundation of the key. As the most stable and harmonically grounded chord, because it contains the root of the key, it creates a sense of resolution and rest. Unlike other chords that create tension and drive harmonic movement, the tonic doesn’t inherently need to move or resolve elsewhere, making it the anchor of the scale’s harmonic structure.

Radiohead's “There There” begins with two bars of B minor, instantly establishing the song's key and tonal center and creating a sense of grounding and stability.

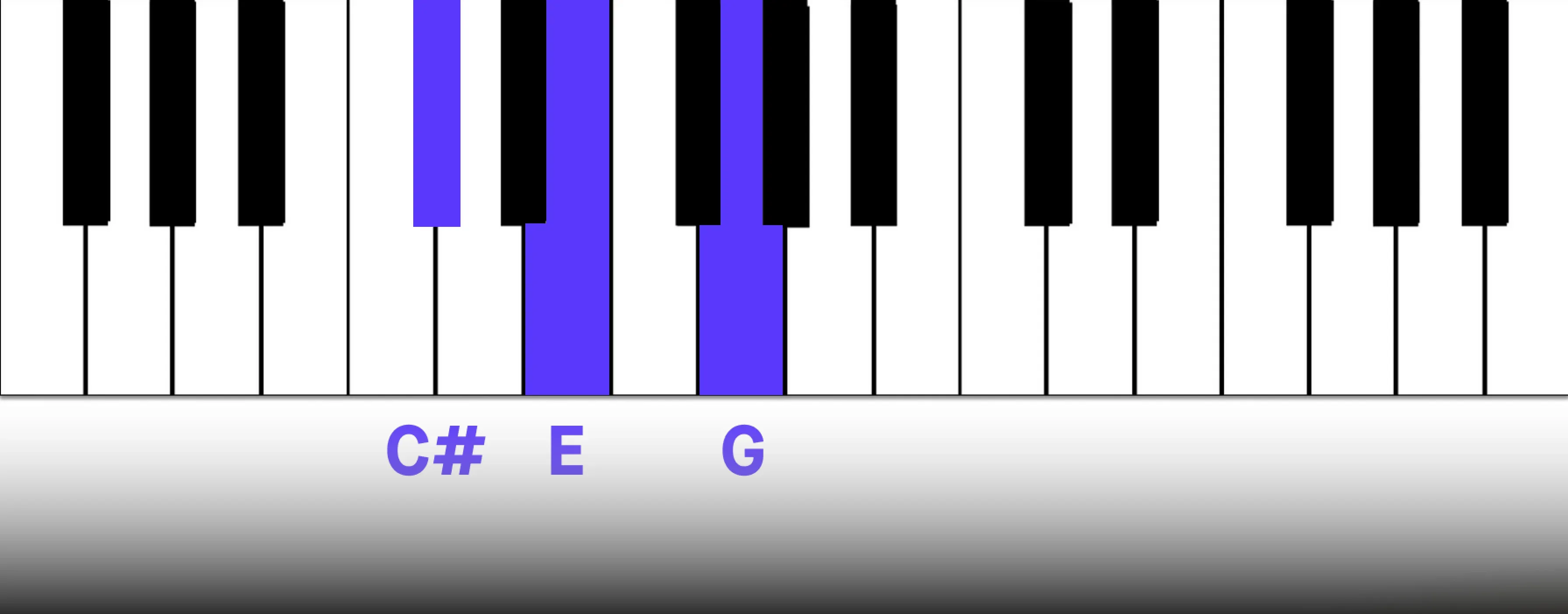

ii°: C# Diminished

Diminished chords are built on unstable and tense tritone intervals (often called the 'devil's interval' due to their inherent dissonance).

In minor keys, the diminished chord built on the second degree (ii°) is often used as a predominant chord, creating tension and anticipation that leads naturally to the dominant and then the tonic, which feels particularly stable following such a dissonant chord.

Holding a diminished chord for an extended time increases anticipation because the unresolved dissonance builds tension, making the eventual resolution feel even more powerful and satisfying.

The diminished chord built on the second degree (ii°) can be harmonically challenging to use due to its dissonance. One way to create a contrasting and more consonant sound is to borrow the major chord built on the lowered second degree from the Phrygian mode (a mode of the B minor scale). <sup id=""> </sup>In B minor, this would be a C natural major chord instead of the C# diminished. This borrowing creates a unique and interesting harmonic color.

This substitution creates a unique tonal character, as heard in the verse of Hall and Oates'"Maneater", which features this very C major chord.

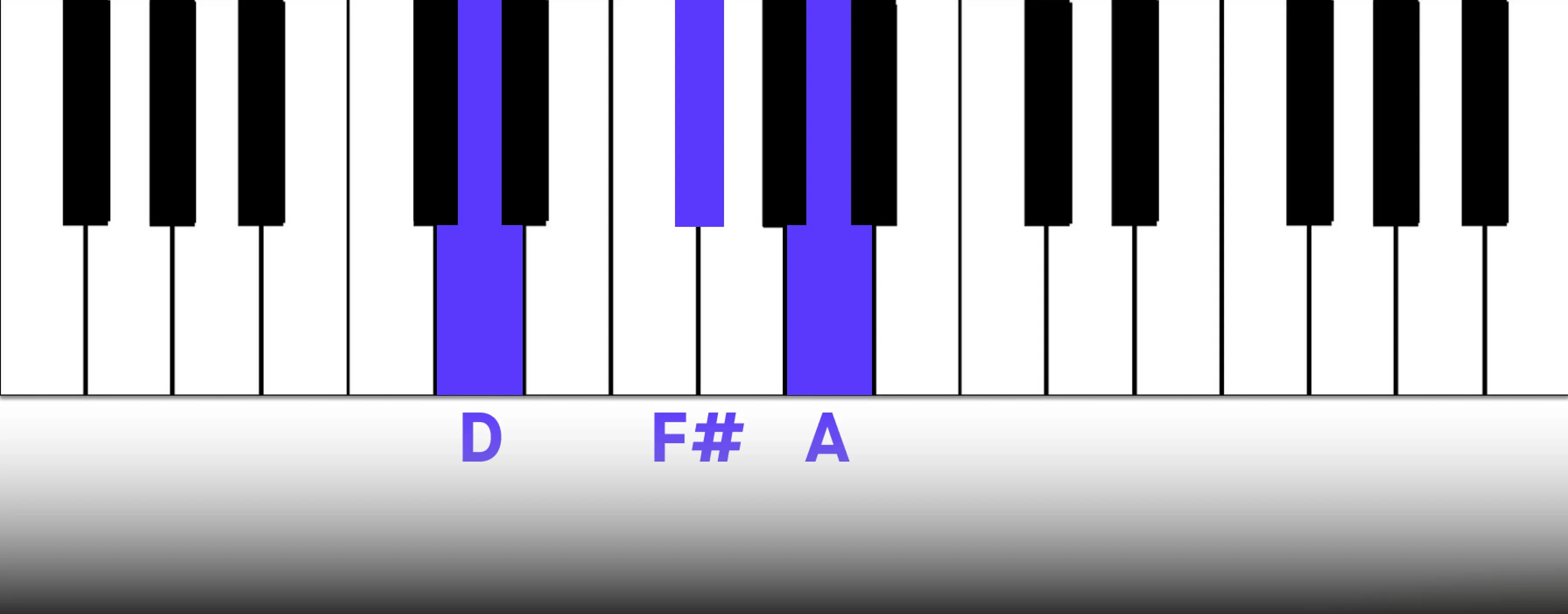

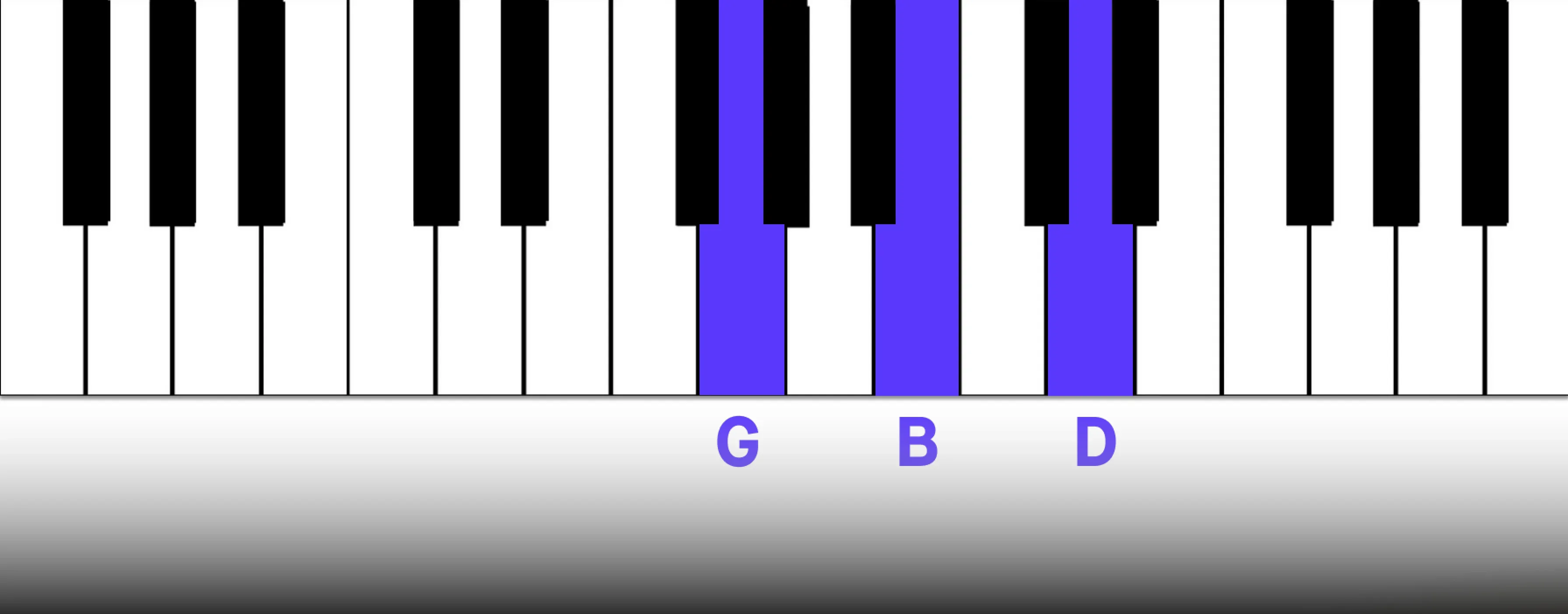

III: D Major

The D Major mediant chord can serve as a tonic substitute, offering a sense of rest while introducing a different harmonic color. Since it shares two notes with the tonic (B Minor), it maintains a sense of familiarity while subtly shifting the tonal character.

Tonic substitutions enhance the impact of the tonic by creating movement, variation, and preventing predictable resolutions, adding depth and interest to a progression. This dynamic approach keeps the listener engaged while maintaining a connection to the home key. Example: Avicii’s “Wake Me Up” features the major III chord within its simple i-VI-III progression. Notably, the verse emphasizes the D major chord over the B minor, creating a more uplifting feel despite the minor key signature. This extended emphasis on the major III subverts the listener's expectation of a typical minor key progression and contributes significantly to the song's anthemic quality.

Fall Out Boy’s “Dance Dance” uses the mediant chord to create a sense of forward momentum while maintaining a connection to the tonic. Because the tonic and mediant share two common tones, they possess a similar tonality, yet their differing qualities prevent the progression from feeling repetitive.

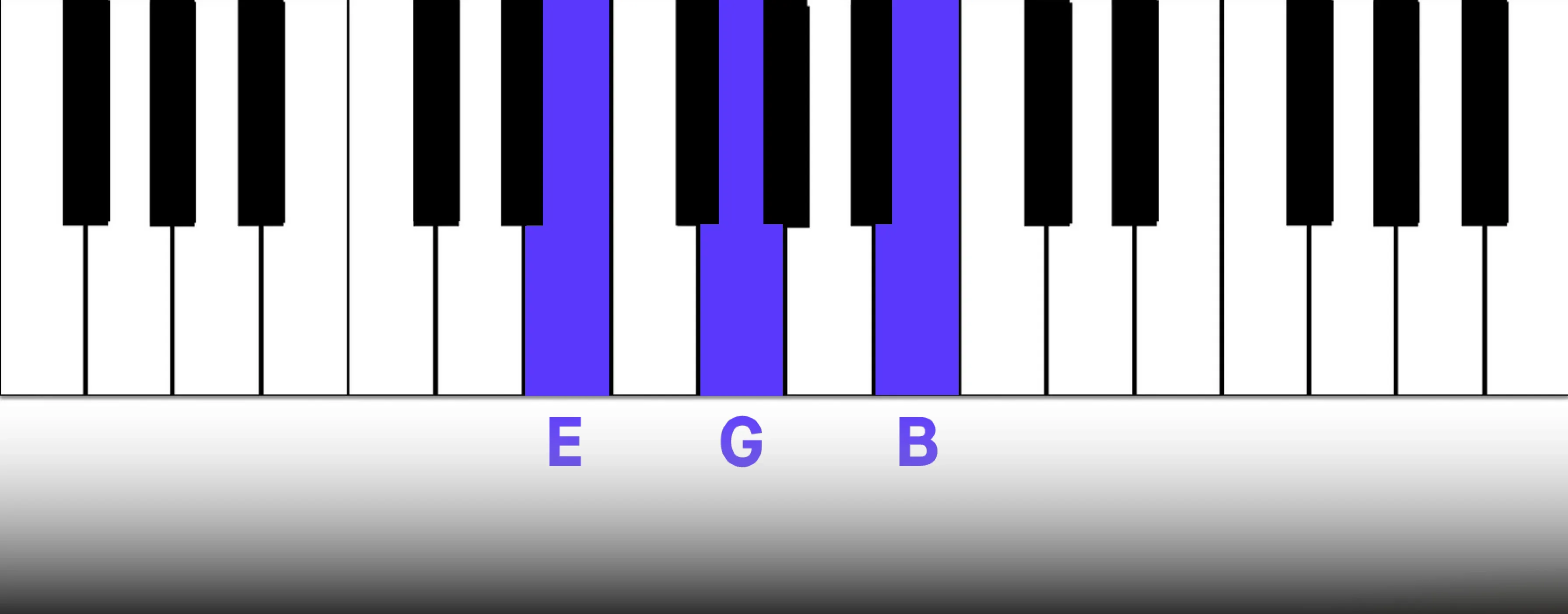

iv: E Minor

The subdominant chord plays a crucial role in creating harmonic contrast and anticipation. By moving away from the tonic, the subdominant creates a sense of tonal departure, setting up the progression toward the dominant, which further intensifies the tension.

When followed by the dominant chord, the tension intensifies due to the specific intervallic relationships created, heightening the listener's expectation for resolution back to the tonic. The subdominant’s function is essential in shaping musical movement, adding depth, and enhancing the emotional impact of a progression.

Example: In M83’s “Midnight City” the progression moves from the VII chord to the iv chord, which takes on a particularly somber quality in contrast to the preceding major chord. This E minor chord then creates a smooth and natural transition back to the tonic, creating a satisfying sense of cyclical movement.

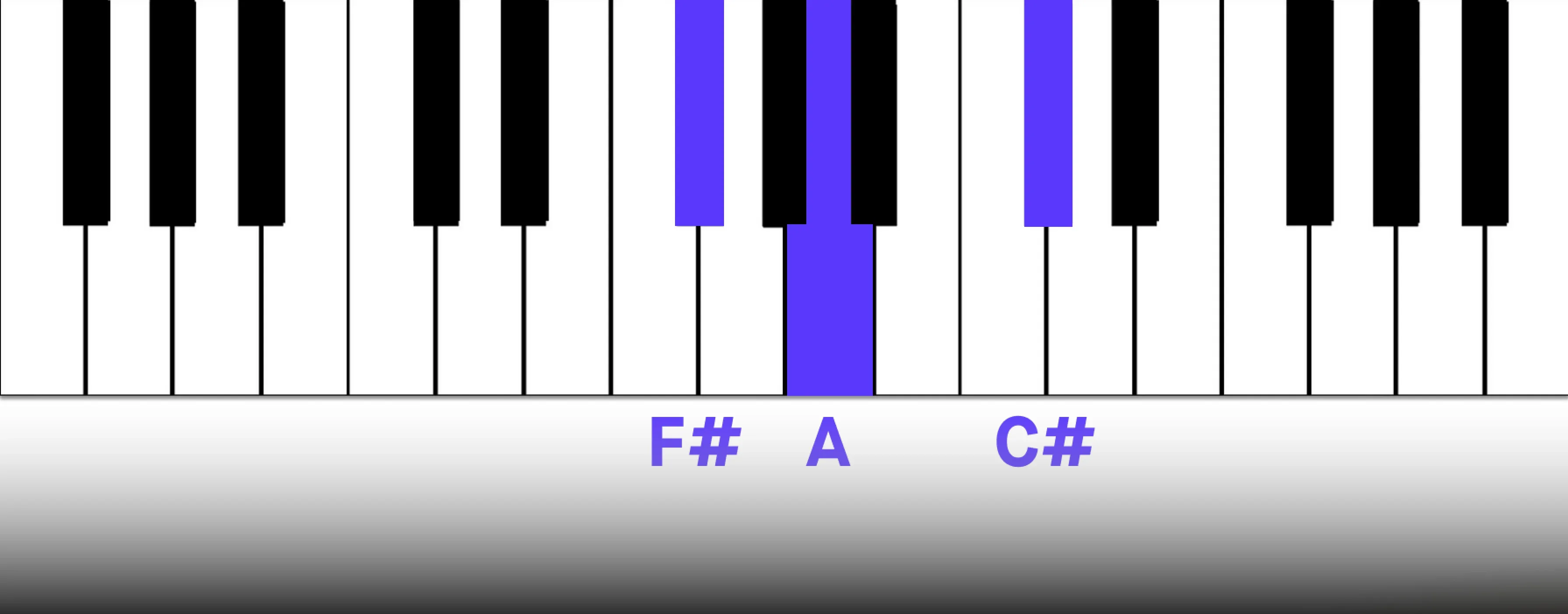

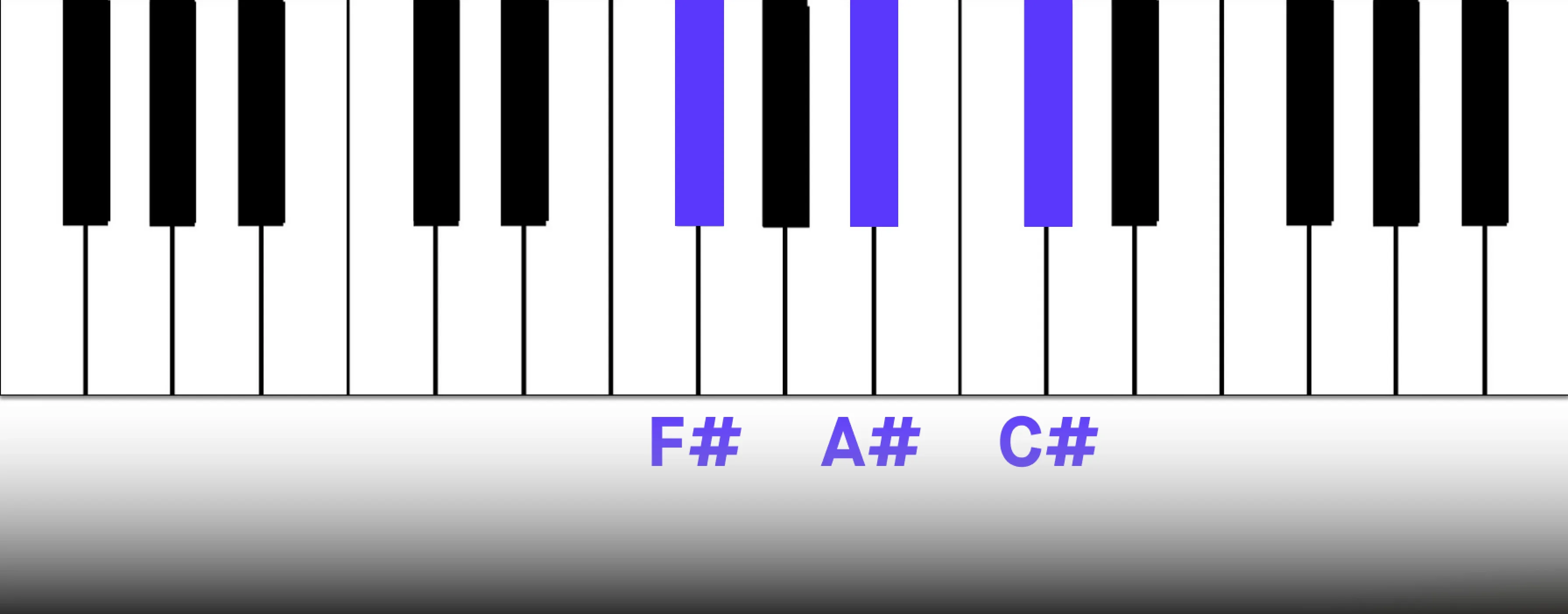

v/V: F# Minor/ F# Major

Alongside the tonic, the dominant is one of the most crucial chords in any key because it creates the strongest sense of harmonic tension and resolution, defining the key's tonal center.

The dominant chord creates tension due to the specific intervals it contains, most notably the tritone between the third and seventh. Additionally, the leading tone (A# in the case of the dominant 7th) is only a half step away from the tonic, creating a strong pull toward resolution.

The dominant seventh chord adds a seventh (E natural) to the dominant triad, further increasing the harmonic tension and creating an even stronger pull toward resolution to the tonic chord.

The dominant chord frequently precedes and resolves to the tonic, especially at the end of musical phrases, reinforcing a sense of closure. However, when a phrase begins on the dominant, it generates immediate energy and direction because the unresolved tension creates a sense of anticipation and a strong desire for resolution back to the tonic.

Example: "Deadmau5's “I Remember” features a major dominant chord that dramatically alters the harmonic landscape. This chord, appearing as the first chord of a measure within a larger progression, effectively replaces the tonic chord that the listeners would expect. This creates an instant and compelling shift in mood, which keeps the listener engaged.

“Hotel California” by The Eagles moves from the tonic to a dominant 7th chord in the first interval of the verse. This creates tension instantly and gives the song a sense of longing and melancholy.

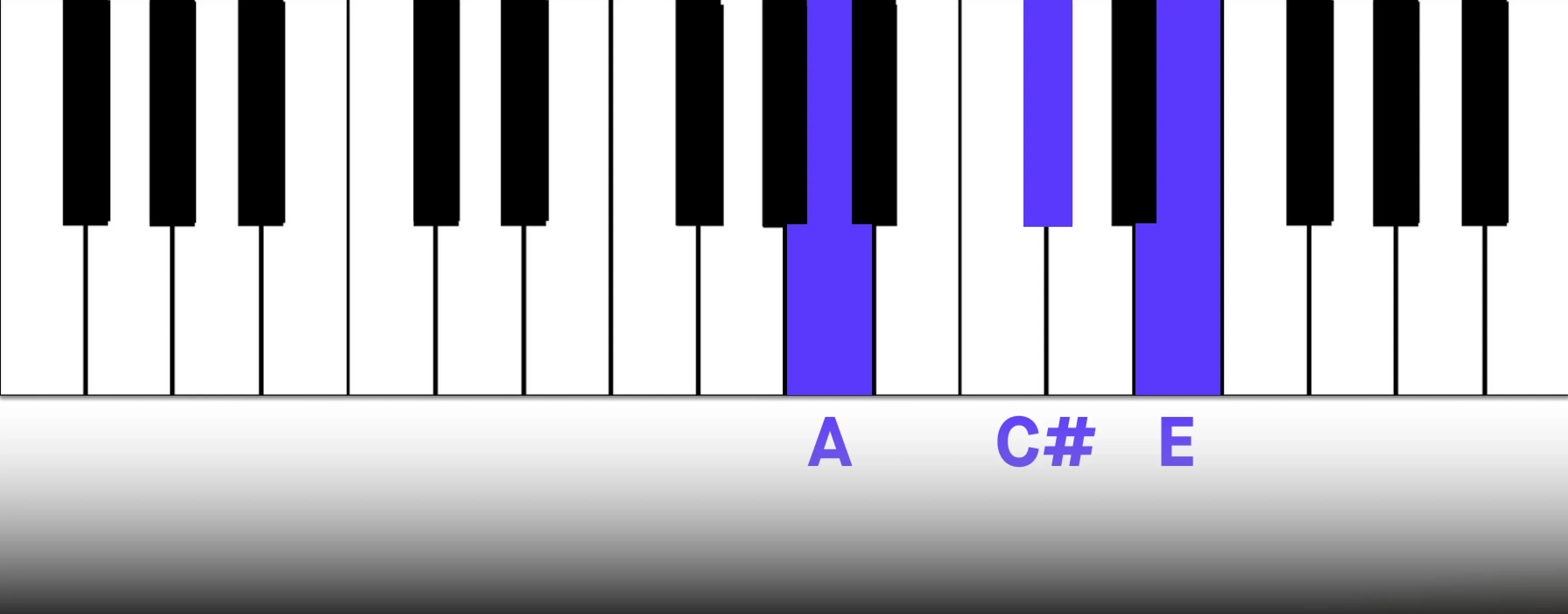

VI: G Major

The G major submediant chord adds a distinct and valuable color to the B minor tonality. Located a major third below the tonic, it creates a sense of harmonic interest and movement within B minor progressions.

Its relationship to the tonic gives it a unique character, often contributing a slightly brighter or more hopeful quality compared to other minor key chords. The G major chord can be used to create smooth transitions to other chords within the key, adding color and complexity to progressions.

Because it shares the notes B and D with the tonic B minor chord, it can also provide a sense of relative stability, even as it introduces harmonic variety. This makes it a useful chord for creating contrast and depth in songwriting.

Example: The chorus to Queen’s “The Show Must Go On” starts on the tonic which moves to the Major VI chord creating a hopeful yet somber harmonic quality. Transitions from the tonic to the mediant and submediant are particularly smooth due to the shared tones between them.

VII: A Major

The subtonic is a versatile chord that can be used in a variety of ways, often creating a descending chromatic line when moving from the tonic to the subtonic and then to the dominant. It works particularly well together with the dominant due to their shared notes.

Rihanna's"Diamonds"makes extensive use of the major VII chord. While this chord, being adjacent to the tonic, typically resolves directly back to it,"Diamonds"takes a different path. It first moves to the mediant chord, used as a passing chord, before resolving to another tonic substitute, the submediant. This harmonic detour adds a layer of complexity and interest to the progression.

With these seven diatonic chords, you can build fantastic progressions in B minor. If you're looking for extra help, Musiversal offers songwriting and production services through the Unlimited Subscription. If you need some inspiration for writing music, check out"30 Unique Songwriting Prompts to Craft Your Next Big Hit".

Adding Depth and Complexity to Chords in B Minor

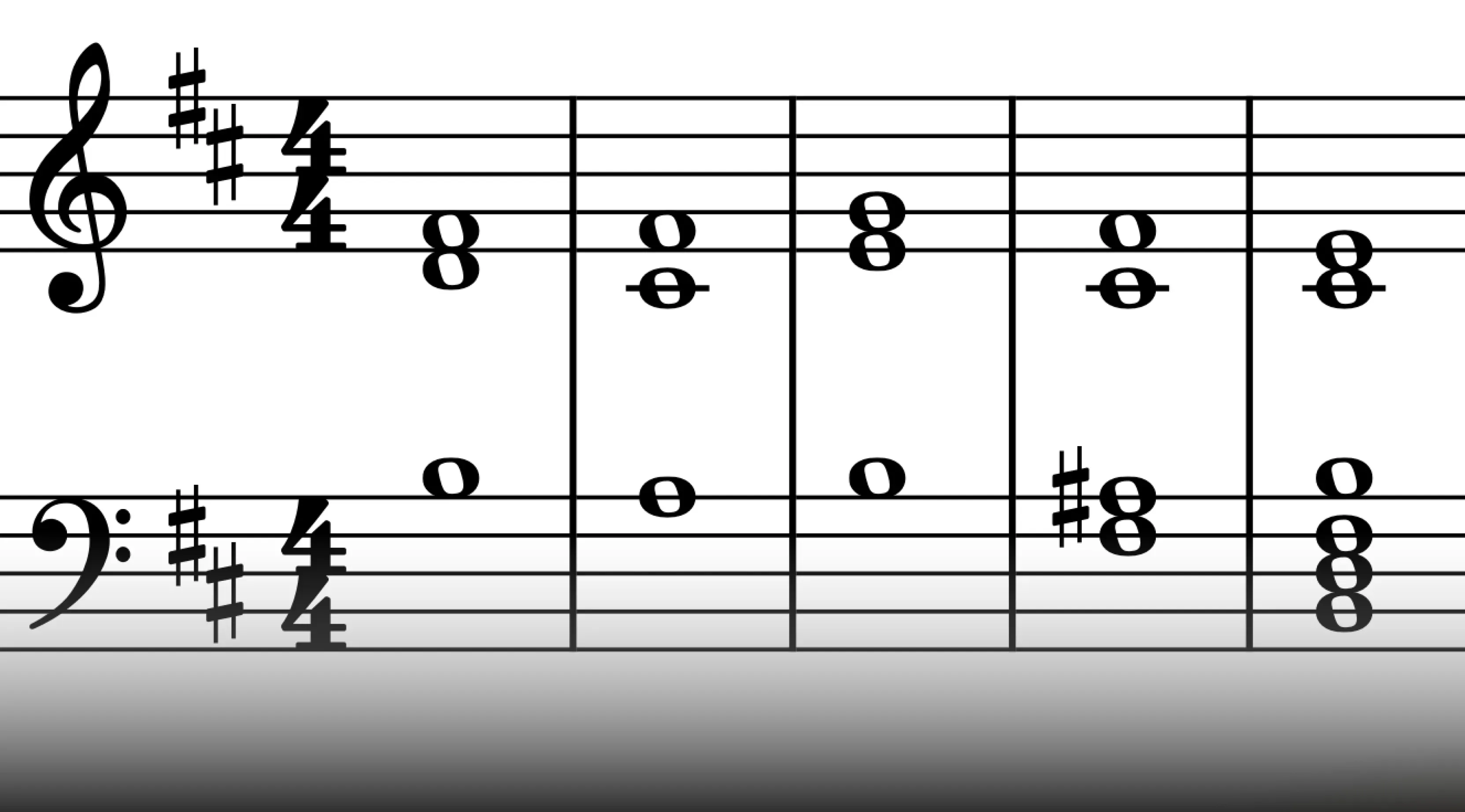

Seventh Chords in B Minor

Seventh chords enrich harmony by adding layers of complexity and color. Built by stacking an interval of a third above the fifth of a triad, they create a more nuanced and expressive sound. When constructed using only diatonic notes, these are the primary types of seventh chords found within a natural minor key: major 7th, minor 7th, dominant 7th, and half-diminished 7th.

Each seventh chord possesses a distinct character:

- Major 7th chords: A major triad with a major seventh added on top. They can evoke a sense of resolution, though not quite as strong as a regular major triad due to the slight dissonance created by the major seventh against the root.

- Minor 7th chords: The minor 7th chords, with their minor third and minor seventh intervals, tend to sound mellow, introspective, and often melancholic. They add depth and emotional resonance to minor key passages.

- Dominant 7th chords: A major triad with a minor seventh. The dominant 7th chords are the powerhouses of harmonic tension. The combination of the major triad and the minor seventh (specifically, the tritone between the third and seventh) creates a strong pull towards the tonic, generating tension and a strong desire for resolution. They are crucial for establishing a key and driving harmonic motion.

- Half diminished 7th chords: Half diminished 7th chords – diminished triads with a minor seventh – create a unique blend of tension and ambiguity. They’re rather unstable and add a touch of mystery or drama to the harmony. The name “half-diminished” comes from the fact that the triad is diminished, but the seventh is only minor, not diminished. It’s common to see this chord labeled as “m7b5”.

The strategic use of seventh chords allows you to write more intricate and emotionally engaging chord progressions by adding more expressive harmonic colors

For a more detailed guide on Seventh Chords in B Minor, take a look at our article “A Comprehensive Tutorial on Creating Seventh Chords in B Minor “.

Learn about diatonic and chromatic chords in B minor with audio and notation examples in this next section. If you're unfamiliar with reading music, Music Matter's Grade 1 Music Theory course on YouTube is a great starting point.

The Diminished Chord

Diminished triads are built on a root, a minor third, and a diminished fifth (a perfect fifth lowered by a half step). The lowered, or diminished, fifth creates a tritone interval with the root, which creates a strong sense of instability and tension, giving diminished chords their characteristic sound.

Chords: Bm - E/G - F#m - D - Cdim - F#m7 - Bm

The distinctive, dissonant sound of a diminished triad arises from its defining interval: the tritone, formed between the root and the diminished fifth. This interval, spanning six half steps, creates instability and a strong desire for resolution.

This built-in tension makes diminished chords exceptionally expressive tools in music, capable of conveying a range of emotions from suspense and unease to drama and intensity, often by creating a strong pull towards a resolving chord.

Natural Occurrence Within Minor Scales

In any minor key, a diminished triad occurs naturally on the second degree of the scale (ii°). The diminished triad on the second-degree shares two notes with the dominant 7th chord. This connection allows the ii° to create a smooth transition to the dominant 7th, which then strongly pulls towards the tonic.

Functions of Diminished Chords

Diminished chords are great for creating dissonance, suspense, and drama in your music. As a staple of jazz harmony, they are used to generate tension and release, adding color and complexity to chord progressions. While less common in mainstream pop and rock, diminished chords still offer expressive possibilities in these genres.

Diminished chords primarily serve two key functions:

- Heightening tension and anticipation: Their inherent dissonance, particularly the tritone interval, creates a sense of instability, building anticipation for a resolution to a more stable chord. This creates a momentary point of unease, enhancing the emotional impact of the subsequent resolution.

- Creating smooth transitions: The diminished chord on the second degree often acts as a predominant chord, creating a smooth transition to the dominant and ultimately the tonic.

Adding Variety and Interest to Chord Progressions

Beyond their functional uses, diminished chords offer a wealth of creative possibilities for adding color and intrigue to harmonic progressions. A particularly effective technique is to diminish a chord that would normally be a standard major or minor triad. This unexpected alteration creates a momentary tension and surprise, injecting a moment of harmonic interest.

This unexpected alteration injects a moment of surprise and harmonic interest, momentarily destabilizing the established harmony before resolving, often back to a chord closely related to the original.

This technique allows you to create subtle shifts in mood by simply injecting variety into otherwise conventional chord progressions. For instance, a simple progression like Bm - G - D - F# could be made more interesting by briefly using a diminished G chord instead of the G major.

A thorough understanding of diminished chord construction and their harmonic function empowers you to write more compelling and emotionally resonant musical phrases with sophisticated harmony.

The Augmented Chord

The augmented chord is built upon a root note followed by two major thirds stacked on top of each other. This results in its characteristic dissonant sound. Because augmented triads do not occur naturally within the diatonic chords of a natural minor key like B minor, their use requires the introduction of chromaticism – notes outside the key.

The inclusion of augmented triads, along with other chromatic elements, allows producers, composers, and songwriters to add complexity, tension, and a sense of heightened movement to their music by creating unexpected harmonic shifts and a strong desire for resolution.

Augmented chords can introduce unexpected harmonic shifts, create smooth modulations to new keys (for example, by acting as a pivot chord), or simply add color and variety to the existing harmonic texture.

Chords: Bm - Gmaj7 - F# - F#aug - Bm

The augmented chord's raised fifth creates an unresolved, ambiguous sound, filled with a unique tension that differs from the dominant and diminished chords.

Uses and Functions

Augmented triads, while not diatonic to major or minor keys, can be used strategically to create moments of heightened tension and dramatic resolution. Two common harmonic applications highlight their unique character:

- Dominant to tonic resolution: Placing an augmented triad on the dominant scale degree and then resolving it to the tonic creates a powerful sense of arrival. This is because the notes of the augmented triad typically resolve by stepwise motion to the notes of the tonic chord, creating a smooth and satisfying resolution.

- Tonic to subdominant progression: Using an augmented triad on the tonic and resolving it to the subdominant chord creates a different but interesting harmonic effect. The augmented triad on the tonic adds a touch of instability, making the resolution to the subdominant feel like a release of tension. The resolution to the subdominant isn't as final as a resolution to the tonic, but it provides a satisfying sense of harmonic movement.

- Using augmented chords within a line cliché: Line clichés, chromatic stepwise motion in a bass line or highest voice, can create augmented chords that result in harmonic tension that adds interest and depth to a chord progression.

Below are a few examples of the augmented chord resolving to a chord that contains the note a half-step above the augmented fifth.

Chords: F#aug (V+)- Bm (I)

Line Cliché:

Chords: Bm - Baug - D - Em

Though unstable, augmented chords offer several valuable musical functions:

- Chromatic and stepwise motion: Augmented chords can facilitate smooth voice leading through chromatic or stepwise motion – creating a seamless connection between the harmonic content of your chord progressions.

- Creating tension and resolution: The inherent dissonance of an augmented chord allows you to create tension and anticipation effectively. This tension is then released when the augmented chord resolves to a more stable harmony, creating a satisfying sense of closure.

- Modulation: The ambiguous nature of augmented chords makes them useful tools for modulation. Because they don't clearly define a single key, their notes can be reinterpreted in a new key, effectively acting as pivot chords to transition to a different tonal center. For example, an augmented chord could share notes with both the original key and the new key, acting as a bridge between the two.

Suspended chords

Sus Chords: Beyond Major and Minor

Suspended chords, or"sus"chords, create harmonic ambiguity by replacing the third of a major or minor triad with either the second or the fourth degree of the scale. A sus2 chord is formed when the third is replaced by the second, while a sus4 chord results from replacing the third with the fourth.

It’s the third that defines whether the chord is major or minor, so substituting it creates a sense of harmonic suspension (a feeling of unresolved tension) and a less defined tonal character compared to traditional triads. They create a sound that lacks the clear tonal direction of traditional triads.

This ambiguity results in a sense of unresolved tension, making sus chords incredibly versatile for expressing a wide range of emotions and atmospheres. From ethereal and dreamy soundscapes to moments of suspense and anticipation, sus chords offer a unique harmonic palette.

This feeling of anticipation allows composers to create ethereal and dreamy soundscapes, moments of suspense, and other nuanced emotional effects. Sus chords offer a unique harmonic palette precisely because of this unresolved quality.

Sus chords serve several key functions in music:

- Creating suspension and anticipation: True to their name, sus chords are great at generating harmonic suspension and a feeling of unresolved tension. This makes them particularly effective in transitional passages, build-ups, or anywhere a sense of anticipation is desired.

- Adding color and texture: Sus chords, with their unique intervallic relationships, introduce subtle harmonic variations and nuances, enriching chord progressions and preventing them from becoming predictable or monotonous.

- Dominant prolongation: The sus4 chord on the dominant degree is particularly useful for prolonging the natural tension of the dominant. Unlike the dominant chord, the Vsus4 doesn't resolve the tritone interval, delaying the resolution and increasing anticipation. The progression Vsus4-V-I is a classic way to create a satisfying resolution and effectively conclude musical phrases. The Vsus4 adds a layer of anticipation before the final resolution to the tonic.

Chords: Bm - Em - F#sus4 - F#7 - Bm

Chords: Bm - Gsus2 - D - A

Suspended chords add a distinctive color and complexity to harmonic progressions. Their emotional impact is highly contextual, shaped by the surrounding harmonies, instrumentation, and tempo. For instance, a sus4 chord in a slow, quiet passage might create a sense of yearning, while the same chord in a fast, loud passage could create a feeling of anticipation.

While both sus2 and sus4 chords create a sense of harmonic suspension, they differ in their tendency to resolve. The sus4 chord, with its perfect fourth interval, has a strong tendency to resolve down to the major or minor third, creating a satisfying resolution.

The sus2 chord, with its major second interval, is less"tense"and often functions more independently within a progression, not necessarily demanding a strong resolution in the same way as the sus4. It can contribute a more open and airy quality to the harmony.

Chords: 7. Bm - Bsus4 - F#sus4 - F#7 - Em - Bm

Mastering suspended chords can unlock a world of creative possibilities for any musician – regardless of genre. Understanding how they’re formed, sound and tonal properties, and their diverse range of applications empowers you to add depth, color, and intrigue to your music.

Suspended Chords in B Minor

Power Chords

Rock music thrives on the raw energy of power chords. These two-note chords (or sometimes three-note chords with an octave doubling the root) consisting solely of the root and fifth, deliver a punchy, adaptable sound that's a cornerstone of the genre. Their stripped-down structure creates a powerful and unambiguous sound.

This allows them to work effortlessly in diverse melodic and harmonic contexts, making them a natural fit for high-energy music. They’re part of the fabric of rock chord progressions.

Since distorted guitar is a hallmark of rock, power chords are instrumental in creating that signature sound. The absence of the third (the note that determines whether a chord is major or minor) is crucial because it eliminates potential harmonic clashes and unwanted dissonance that would become exaggerated and muddy under distortion, allowing the powerful root and fifth to cut through the mix.

Beyond their sonic qualities, power chords are incredibly player-friendly, particularly on guitar. The consistent hand shape and straightforward movement across the fretboard make them accessible and efficient for building powerful riffs and progressions.

Chord Inversions

Chord inversions occur when a chord tone other than the root is placed in the bass. This simple shift can alter the character of the chord quite dramatically because the bass note has a strong influence on the overall sound and feel of the harmony.

- 1st Inversion: The third of the chord is in the bass.

- 2nd Inversion: The fifth of the chord is in the bass.

- 3rd Inversion: The seventh of the chord is in the bass. (This applies specifically to seventh chords).

These inversions can significantly impact the sound and feel of a chord progression, adding smoothness, variety, and harmonic interest. In the following section, we'll explore the various reasons for incorporating chord inversions beyond basic triads.

Smooth Voice Leading

While the bass note defines the inversion, the overall voicing of a chord – the specific arrangement of all its notes – also contributes to its tonal character. The specific intervals created between the notes in a given voicing influence the overall color and feel of the chord.

Rearranging the notes within a chord, within any given inversion, can subtly alter the sound and stability of the chord.

One of the primary reasons to get used to inversions is to create a smoother voice leading between chords. By minimizing the intervallic leaps between individual notes in successive chords, inversions facilitate a more stepwise, connected, and ultimately more pleasing musical texture.

This smooth voice leading contributes to a more fluid and elegant harmonic flow, which is particularly important for larger arrangements where many instruments are playing different parts. Smooth voice leading helps to prevent muddiness in the lower register and ensures that the individual parts blend well together, creating a cohesive and polished sound.

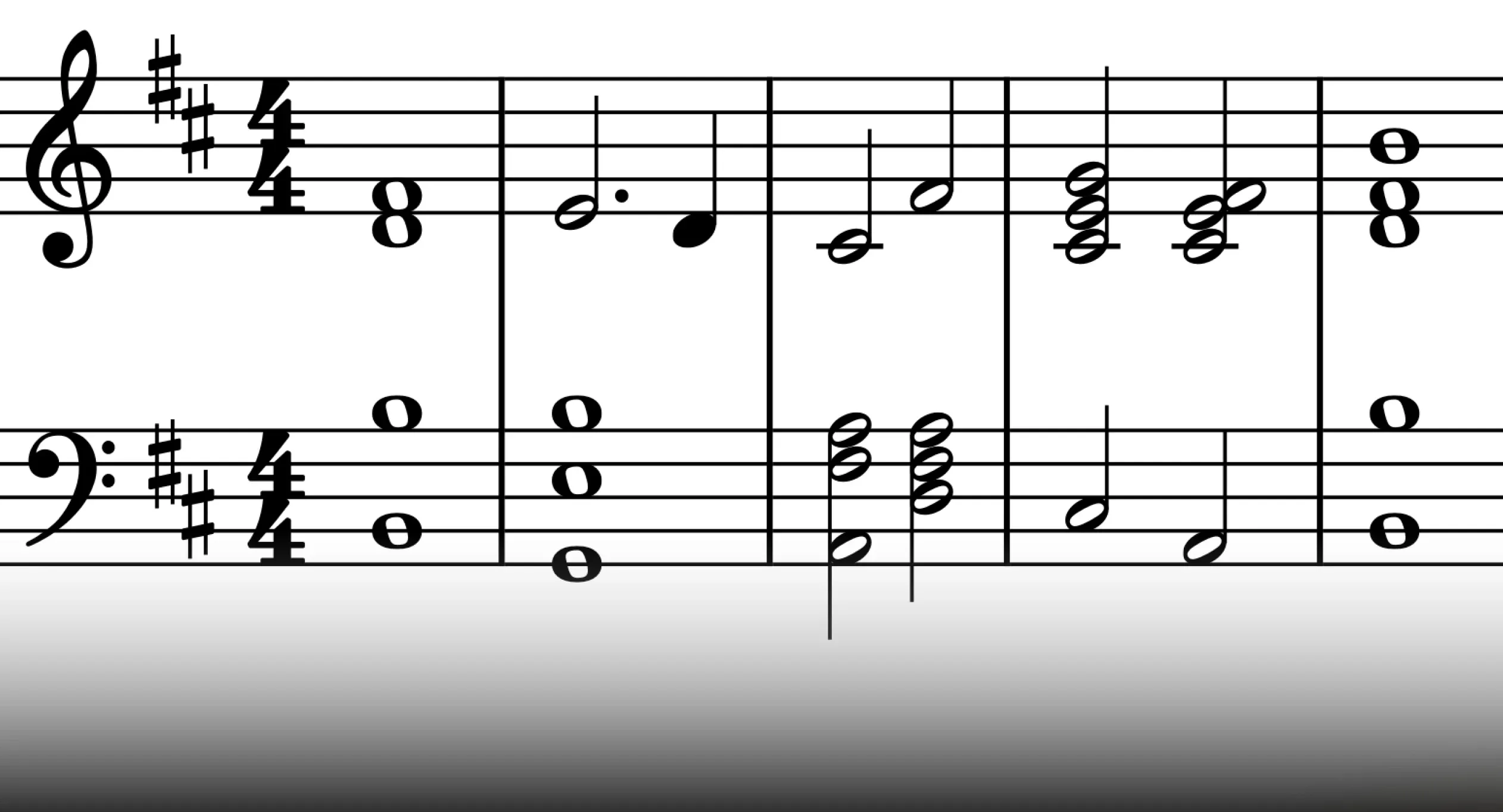

Below is an example showing how inversions can be used to create smoother transitions within a chord progression. This also showcases how stable chords in root position can feel followed by inverted chords.

Chords: Bm - F#/A - Em/B - F# - Bm

When writing music for multiple instruments, it’s particularly important to keep voice leading in mind as you’re writing for the different parts. Good voice leading, by minimizing large leaps and unwanted dissonances, helps with the balance and clarity of the music, ensuring that each instrument's part contributes effectively to the overall harmonic texture.

With the help of chord inversions, you can create nice and smooth descending or ascending basslines to build anticipation.

Chords: Bm - D/A - E/G - Bm/F# - Dsus2/E - A - Bm

Stability and Sound

Chord inversions offer subtle shifts in a chord's stability and overall sound, due to the changing relationship between the bass note and the other chord tones, adding expressive depth and variety without introducing dissonance.

Root position chords typically project a sense of grounded stability because the root of the chord, the tonal center, is in the bass, while inverted chords, with a different note in the bass, can create a feeling of motion or a lessened sense of resolution. This allows for harmonic variety without harshness.

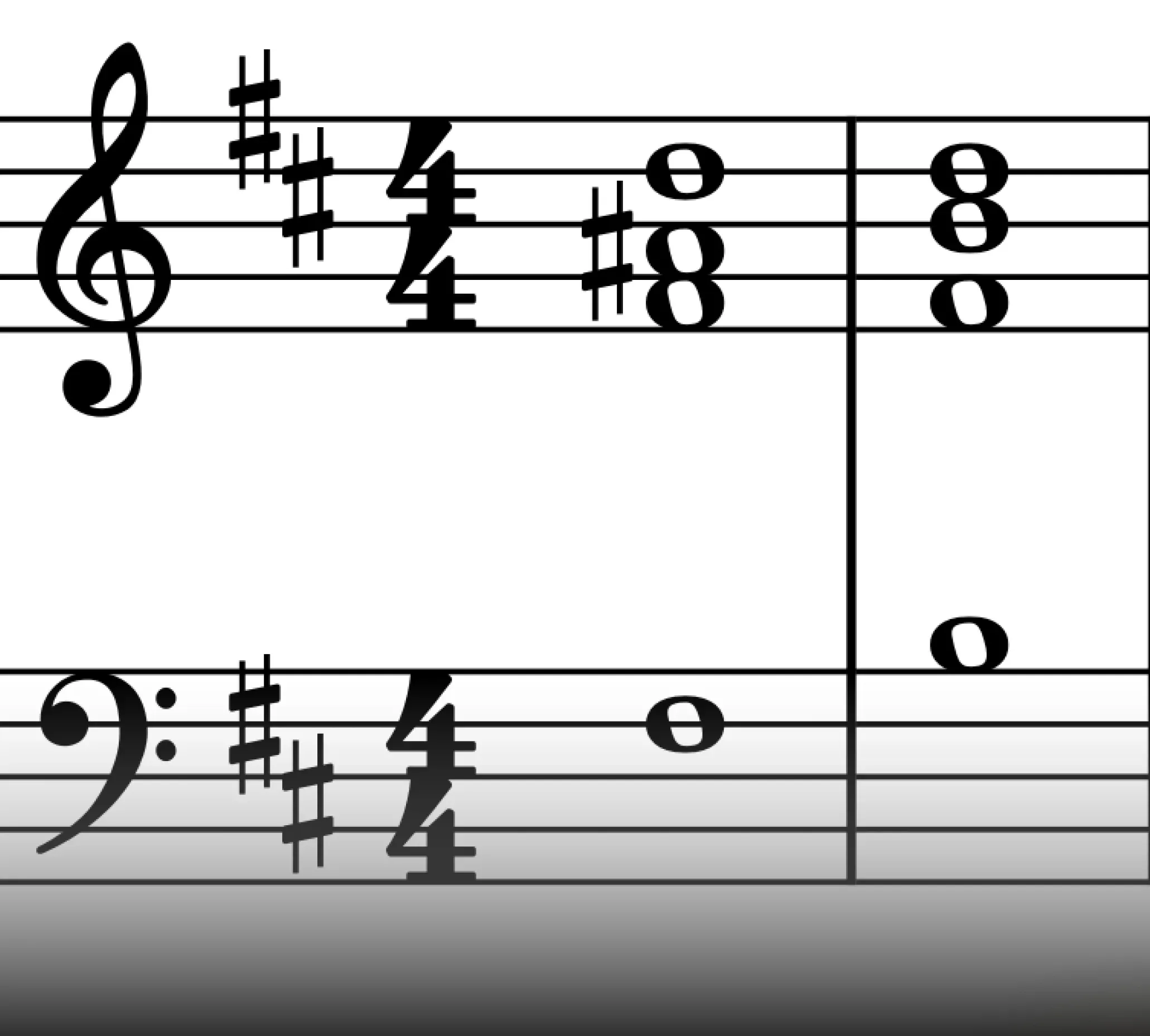

Chords: Bm/F# - F#/C# - Bm

Using inversions of the tonic chord is a powerful technique for creating nuanced approaches to harmonic stability and the home key. Different inversions of the tonic chord offer varying degrees of stability, allowing you to subtly control the sense of resolution and arrival.

Beginning or ending phrases with inverted tonic chords add a layer of sophistication. Returning to the tonic in different inversions avoids the feeling of constant resolution, allowing for a more fluid harmonic movement.

For instance, a piece might start with the tonic chord in root position, projecting a strong sense of stability. Then, the same tonic chord can be explored in various inversions, subtly altering the harmonic color and character. The first inversion might create a slightly more flowing feel, while the second inversion could add a touch of lightness. This adds depth and interest while firmly establishing the tonal center.

Chord inversions bring subtle nuances and richness to harmonies. By offering varying degrees of stability and a wider range of bass line options, they unlock a broader palette of voicings and textures, leading to a more dynamic and engaging listening experience.

Learn How to Recognize Intervals

Practicing your interval recognition skills is crucial for working with triads, inversions, and altered chords (diminished or augmented). The ability to quickly identify intervals streamlines the songwriting process, allowing for more intentional choices and minimizing trial and error when selecting the right chord or melody note.

For instance, if you hear a melody that moves up by a perfect fourth, recognizing that interval immediately allows you to identify potential chord tones or create harmonizing parts.

Training your ear to recognize the distinct sound of each interval grants you greater control over your musical creations, allowing you to write more efficiently, make more informed harmonic choices, and ultimately express your musical ideas more effectively.

Our article “Ear Training: Songs to Practice Intervals” provides a curated list of songs for both ascending and descending intervals to help you develop this essential skill.

What’s next?

Learn how to write unique and interesting progressions for your next song with our comprehensive guide in B Minor chord progressions. We look at how B minor chords are used in popular songs and explore interesting harmonic tricks to take your music to the next level.

This in-depth exploration of B minor harmony examines the effective use of both diatonic and chromatic chords, drawing inspiration from analyses of popular songs in the key.

Discover how to inject intrigue and flavor into your music using techniques like tonic substitutions, secondary dominants, chromatic mediants, and other devices that create unexpected harmonic shifts, captivating your listeners. The guide also touches upon the use of key changes to further enhance the musical journey.

Musiversal: For Musicians, by Musicians

Elevate your music with unlimited recording sessions and access to over 80 professional session musicians and engineers. Our Unlimited membership puts it all at your fingertips.

Find the perfect musicians for your song – from drummers and cellists to guitarists, string players, pianists, wind instrumentalists, bassists, beatmakers, and much more. Simply choose a convenient time from their schedule and join your live recording session via a dedicated link. Hear your music come to life as you collaborate with the musician in real time.

Don't have a finished song yet? We offer songwriting services, production advice sessions, and even"meet and greets"with artists to discuss your project and recording process. Our engineers also provide professional mixing and mastering to polish your tracks.

And to help you reach a wider audience, we offer marketing sessions to get your music heard.

For valuable insights on music theory, songwriting, creativity, production, gear, marketing, and distribution, check out the weekly Musiversal Blog. Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive Musiversal discounts, inspiring session highlights, helpful marketing tips, and more!

[CTA:community]

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist