Learn the Chords in E Minor: A Music Theory Resource

Master the E Minor Key: Discover essential chords, useful progressions and techniques to elevate your music production and composing skills.

Introduction

A strong foundation in music theory is essential for translating your musical visions into reality. Understanding the building blocks of harmony, such as diatonic and chromatic chords and their relationships, is key to crafting compelling chord progressions with a sense of movement and development.

In this article, we'll analyze the E minor key signature. You'll learn how to:

- Identify diatonic chords: Identify and become familiar with the seven diatonic chords in E minor and learn how to use them to create interesting chord progressions.

- Harness common progressions: Discover popular chord progressions that generate powerful musical tension and resolution within the E minor key.

- Employ modal interchange: Explore techniques like secondary dominants, parallel chords, and relative key signatures to add complexity and intrigue to your E minor chord progressions.

By the end of this guide, you'll have a deeper understanding of fundamental music theory, empowering you to write more sophisticated and captivating music.

The Basics of E minor

The three standard minor scales are natural, harmonic, and melodic minor. Unless otherwise stated, the term "minor scale" generally refers to a natural minor scale.

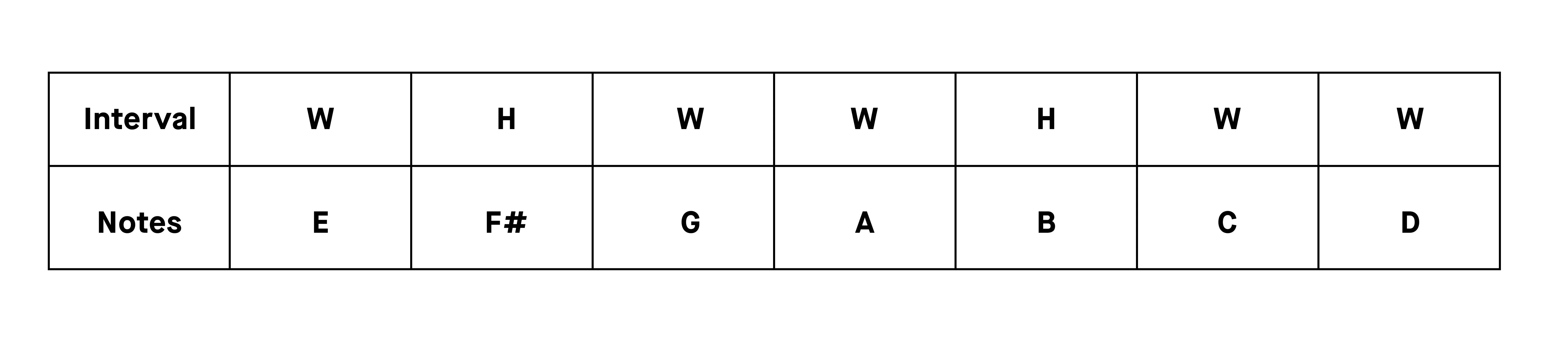

The E Minor scale follows a unique pattern of whole and half steps, which defines the Aeolian mode.

Every note within a scale holds a specific position, known as its scale degree. This placement dictates its harmonic function and its role within the key's chordal framework. The harmonic function of each note and chord is determined by its relative tension level and characteristics in relation to the tonic chord. In other words, the chord's stability or instability within the harmonic context of the tonic.

- E - Tonic

- F# - Supertonic

- G - Mediant

- A - Subdominant

- B - Dominant

- C - Submediant

- D - Leading Tone

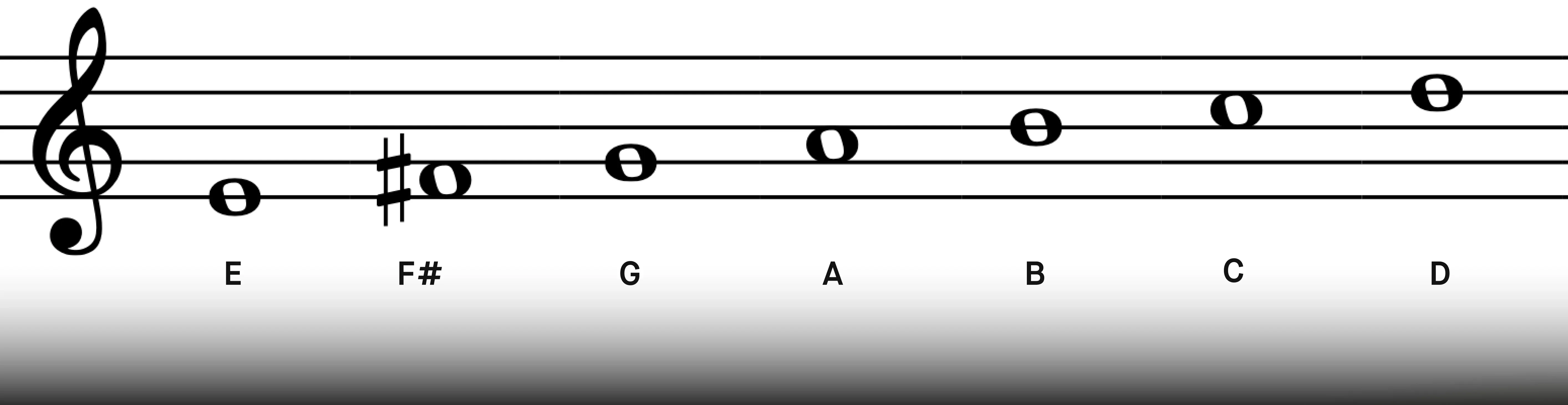

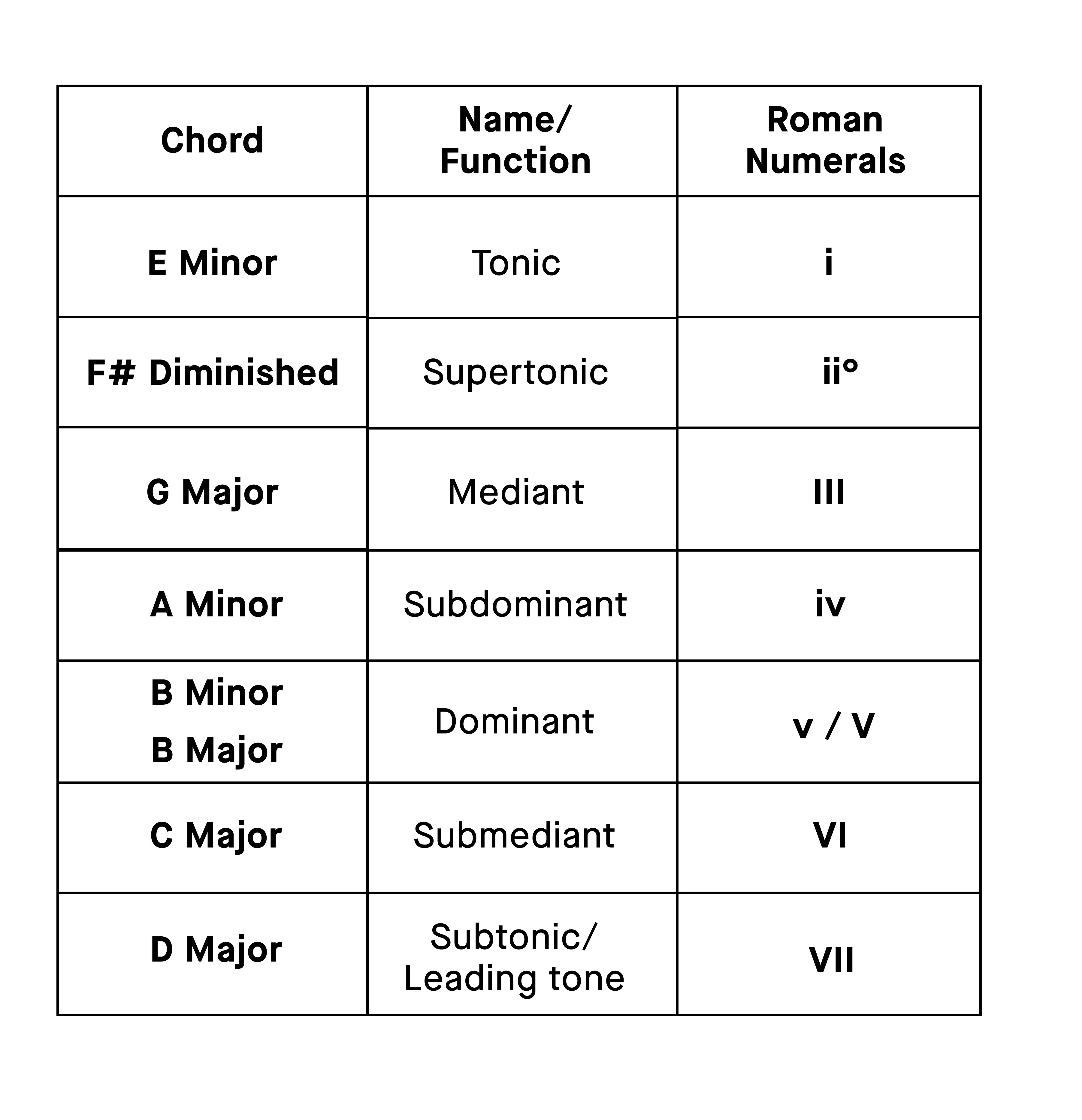

Roman numerals are used to indicate a chord’s harmonic function and quality (major or minor). Uppercase Roman numerals represent major chords, while lowercase Roman numerals signify minor chords. The specific Roman numeral assigned to each chord is determined by its scale degree and harmonic function within the key.

The seven naturally occurring notes of the E minor scale are derived from the Aeolian mode's whole-step and half-step pattern. The remaining notes are called chromatic notes. These can be used to add harmonic richness and access non-diatonic chords in your chord progressions.

Furthermore, chromatic notes can add tension, be used to transition to different keys and alter the natural chord quality of any diatonic chord for more harmonic interest. We'll delve deeper into the techniques for adding interest to chord progressions in the section "Adding Complexity to E minor Chords".

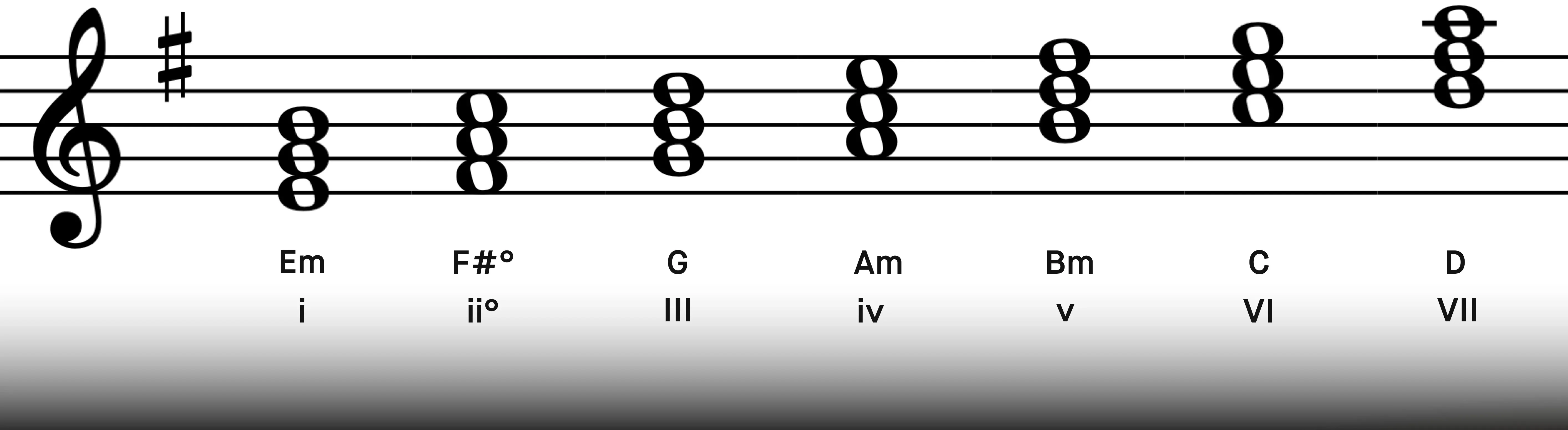

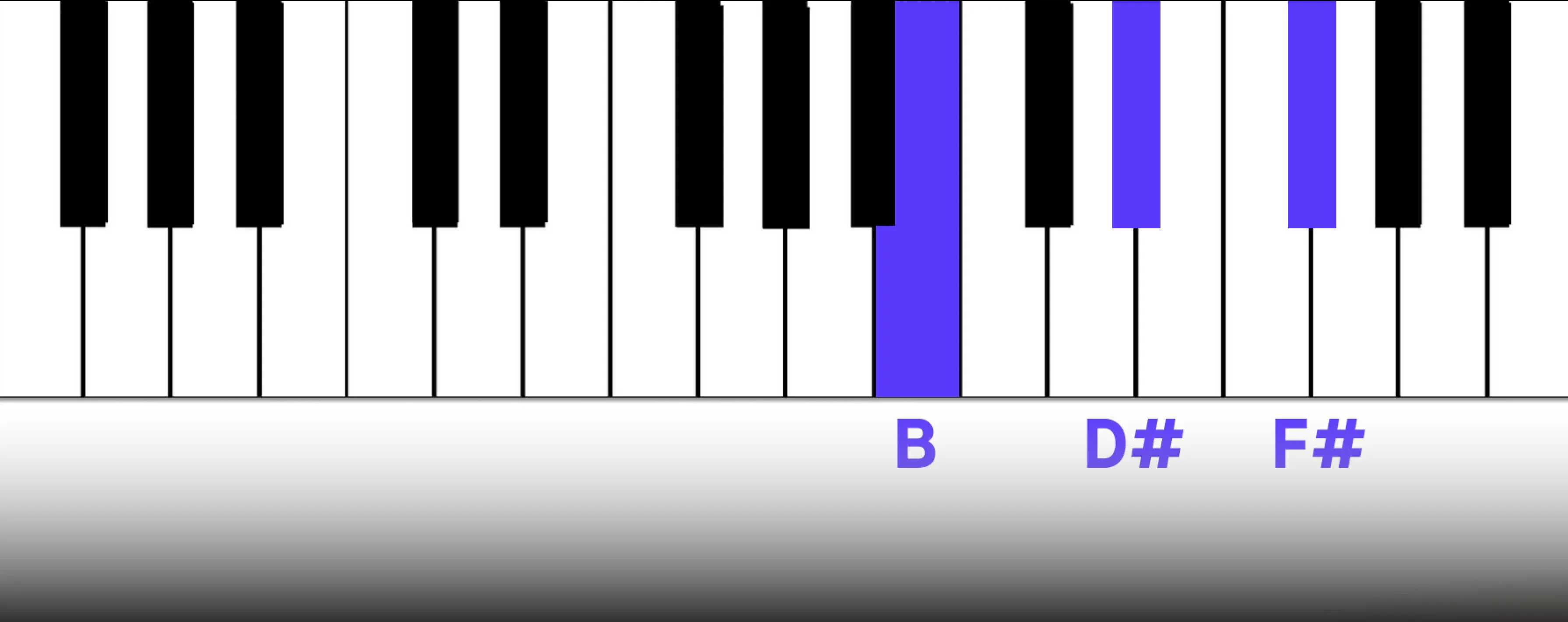

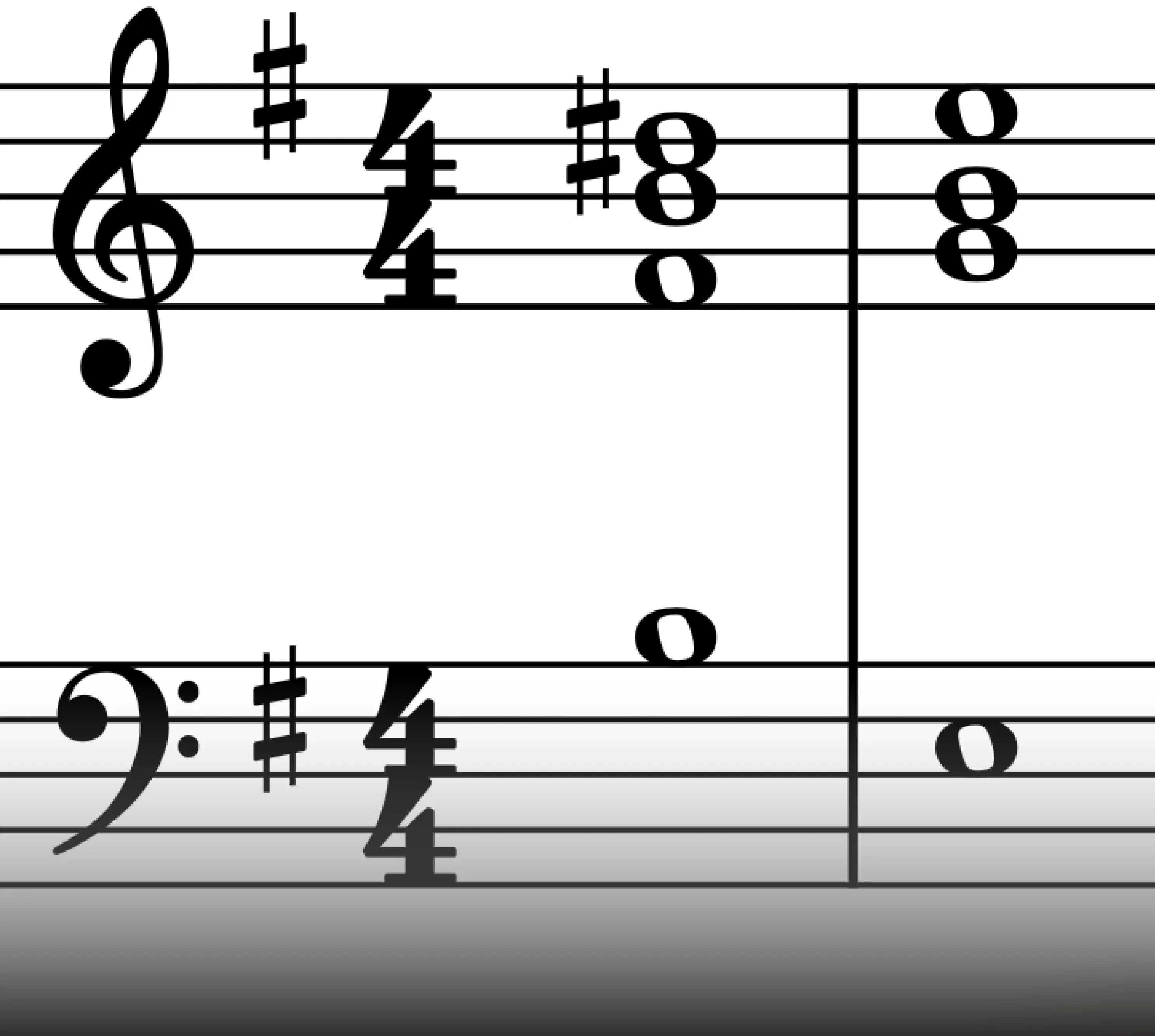

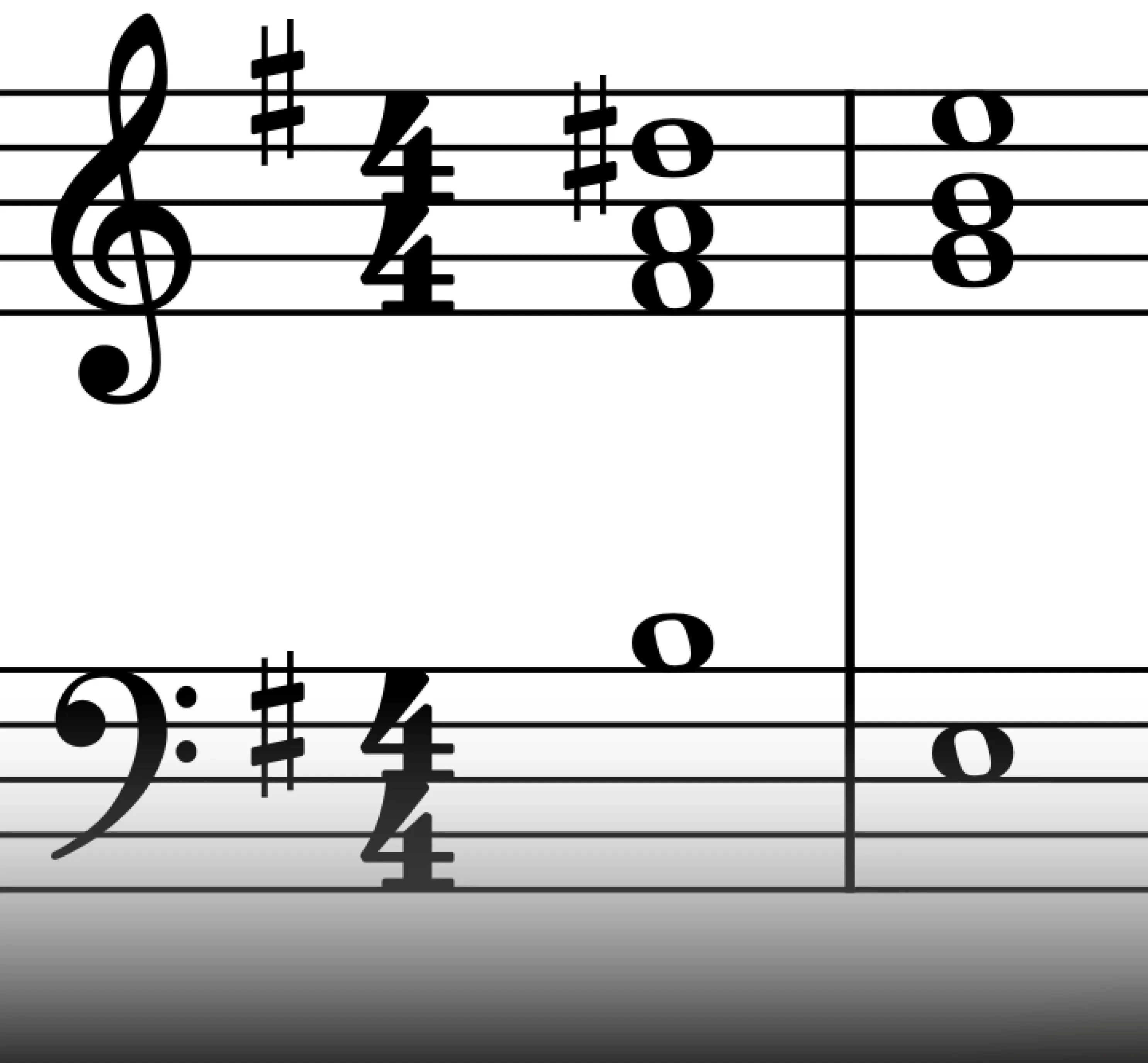

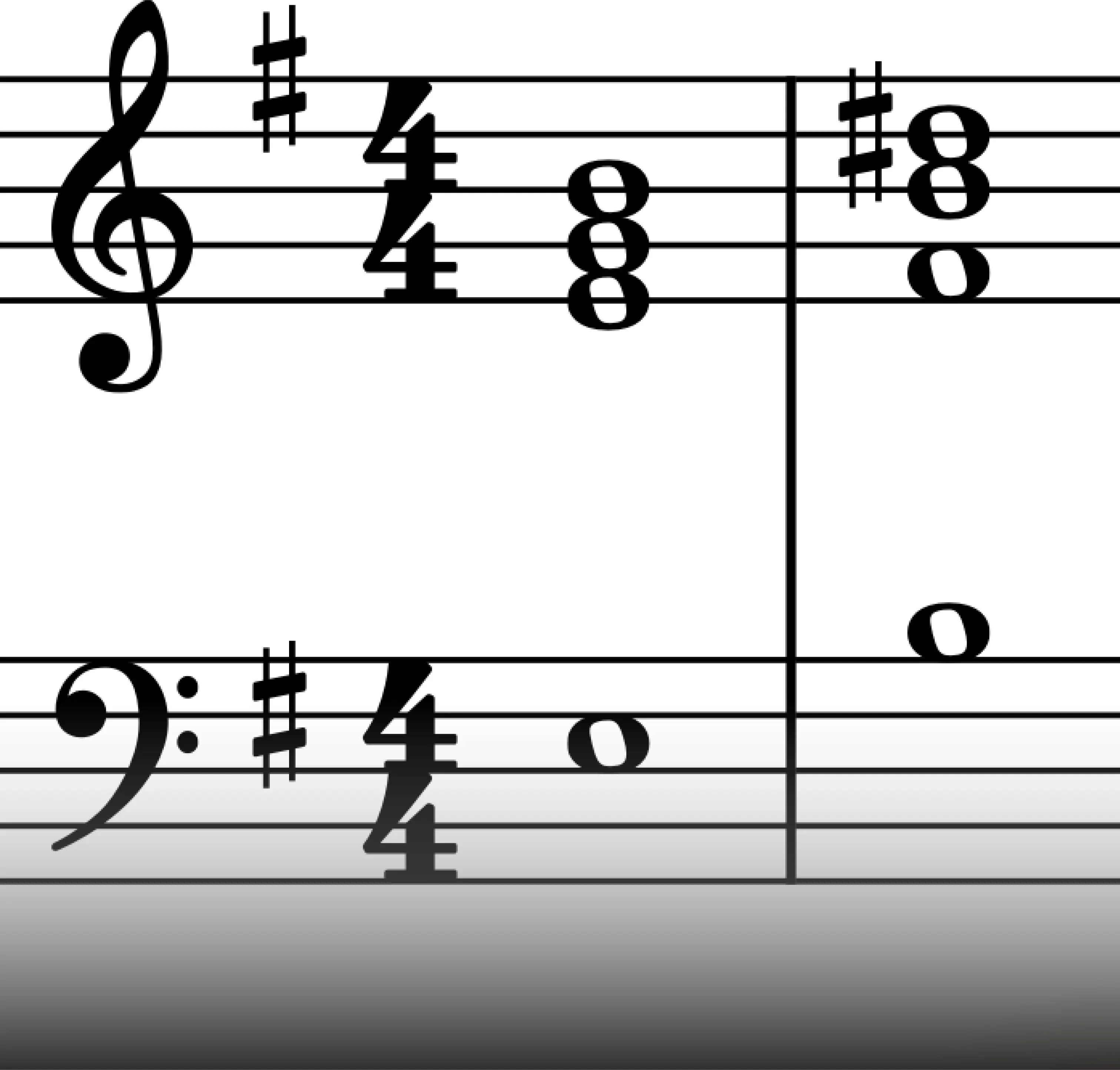

Raised Seventh and Major Dominant Chord

Raising the seventh scale degree is a common technique for songs in a minor key. In E minor, this means sharpening the D to D♯. This alteration transforms the subtonic into a leading tone, which is only a half-step away from the tonic. This stronger pull towards the tonic creates a more decisive and satisfying resolution.

By raising the note, we also transform the dominant chord from minor to major. A major dominant chord in a minor key is considered a chromatic chord because it contains at least one non-diatonic note. This particular alteration, turning a minor dominant into a major dominant, is a widely used technique across various genres and styles of music.

Diatonic notes can be modified through the use of accidentals. Sharp (♯) and flat (♭) symbols indicate these alterations, while a natural (♮) symbol is used to restore a note to its original diatonic pitch.

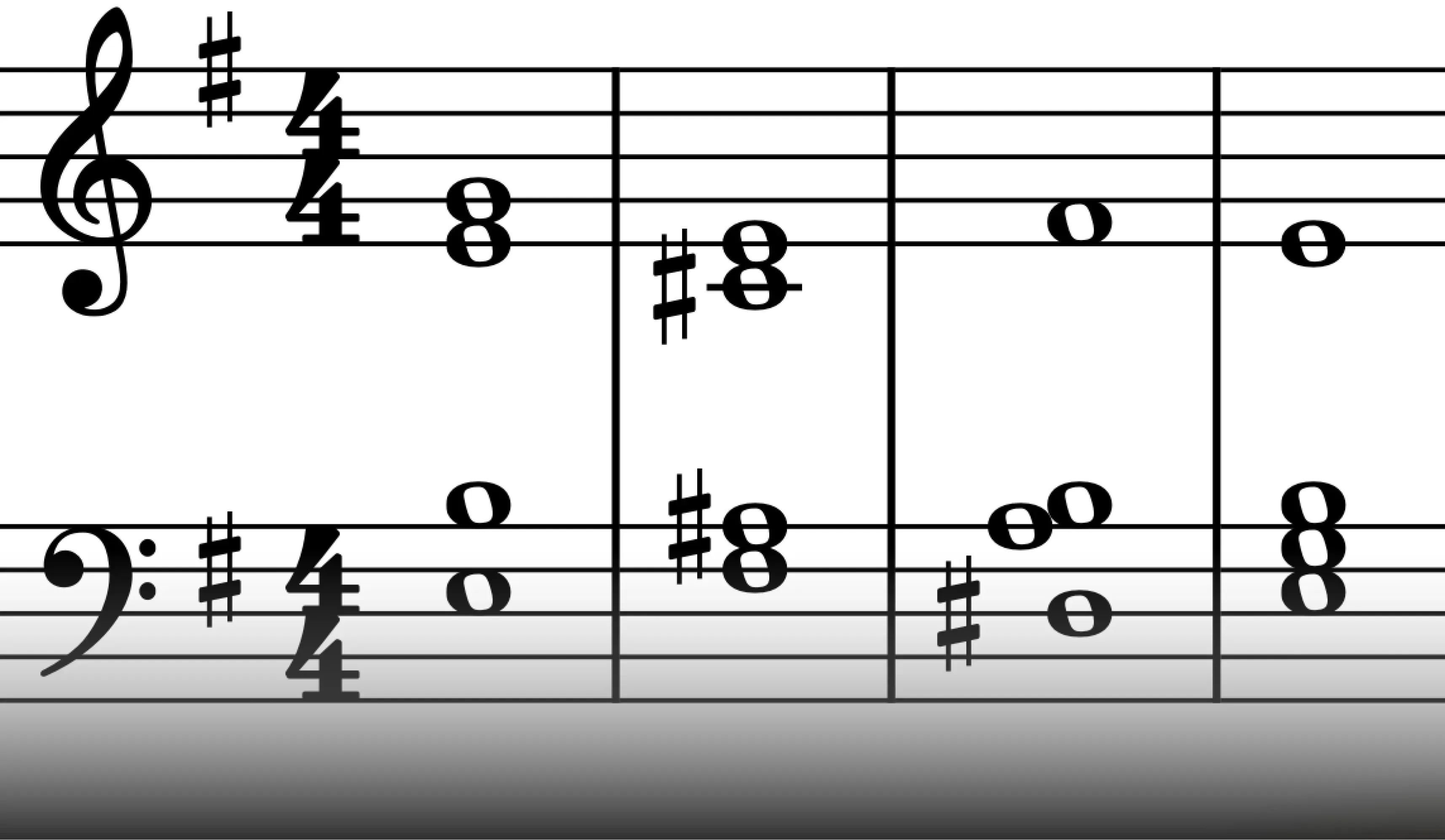

Chords in E minor

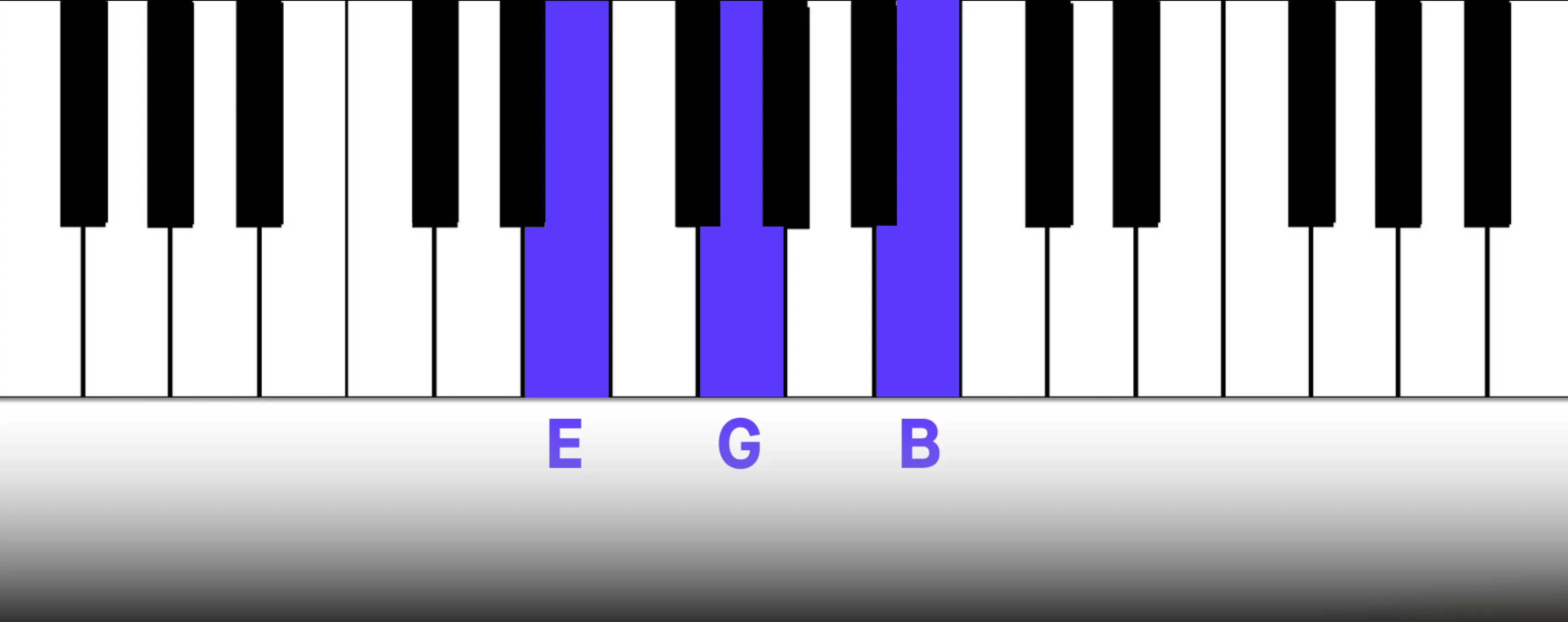

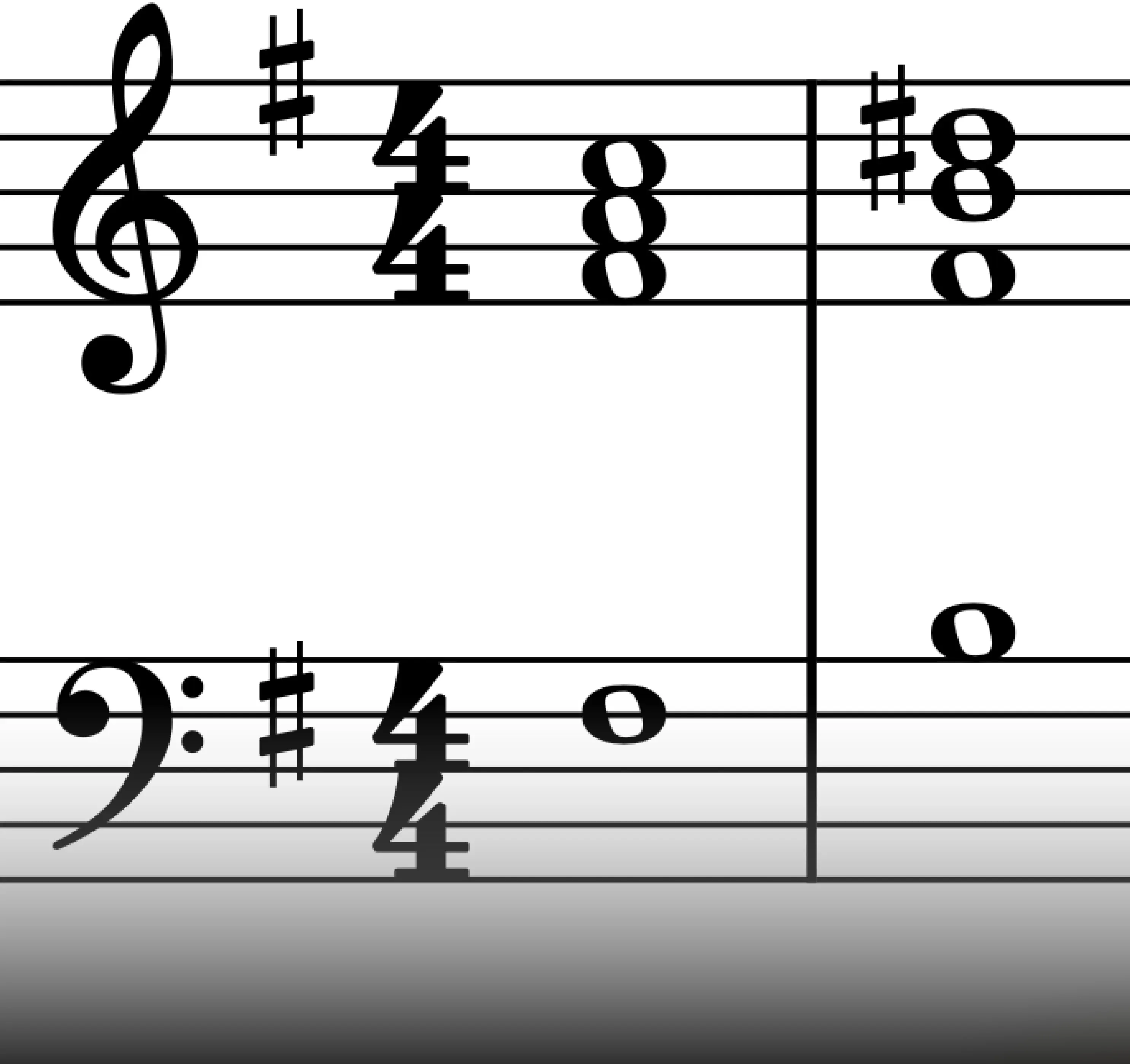

i: E minor

The tonic note serves as the foundation of the scale and key signature, providing a sense of stability and resolution. Chord progressions that conclude on the tonic chord offer a satisfying sense of closure, similar to bringing the chords and notes back home.

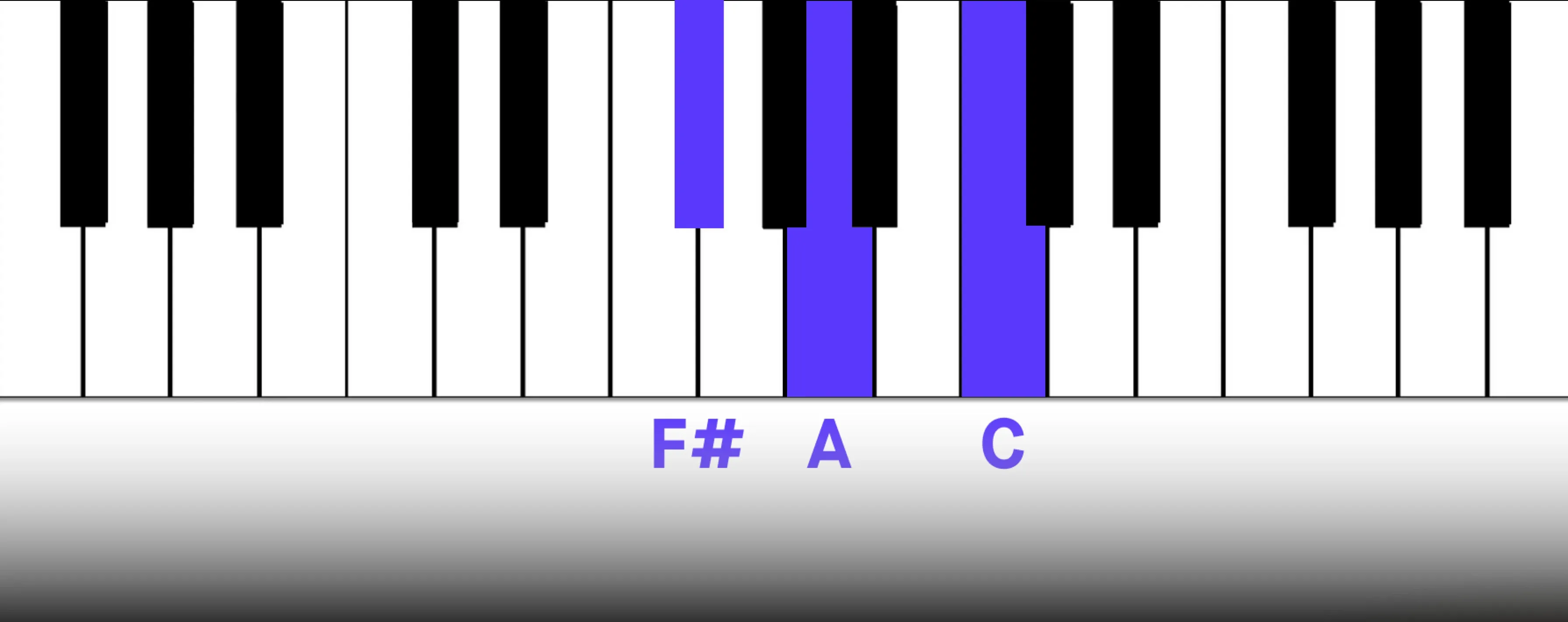

ii°: F# Diminished

The diminished supertonic chord functions as a leading-tone chord, creating tension and strongly implying resolution to the tonic chord. Both the supertonic and dominant chords contribute to a sense of harmonic instability, driving the progression towards the stable resolution of the tonic chord.

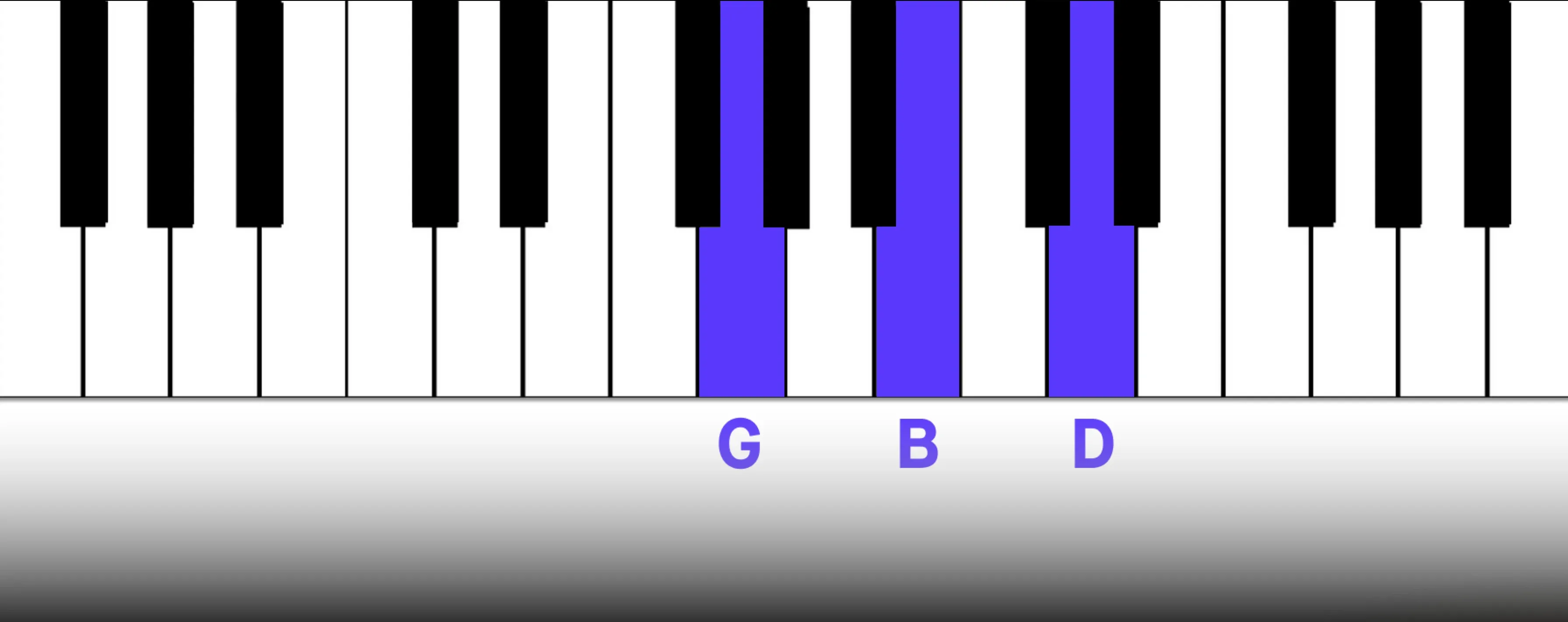

III: G Major

The tonic and mediant chords, though sharing two notes and a similar tonal center, contrast in their respective major and minor qualities. Because they share two common tones, mediants can be used as tonic substitution chords.

By strategically replacing the tonic with the mediant, especially in verses, you can heighten the impact of the tonic chord when it returns in climactic moments like choruses or cadences. Additionally, tonic substitution offers a versatile tool for introducing variety and avoiding predictable resolutions.

The mediant scale degree also aligns with the key signature of the relative major key, making it an excellent chord for modulation and tonal shifts. We'll explore relative keys in more detail later.

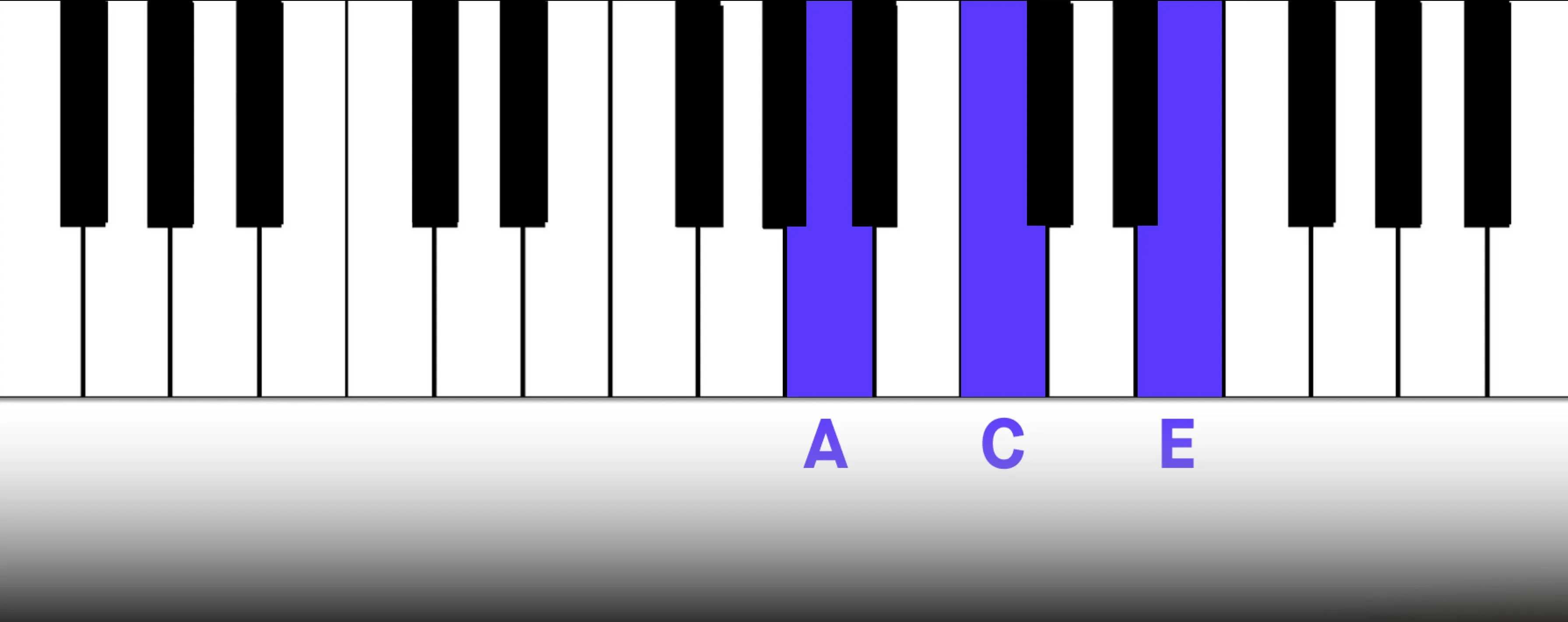

iv: A Minor

The subdominant chord provides a versatile harmonic foundation by offering both contrast and anticipation - especially in an i-iv interval. Its natural progression to the dominant chord builds tension, while its movement to the minor vi chord creates a satisfying harmonic shift.

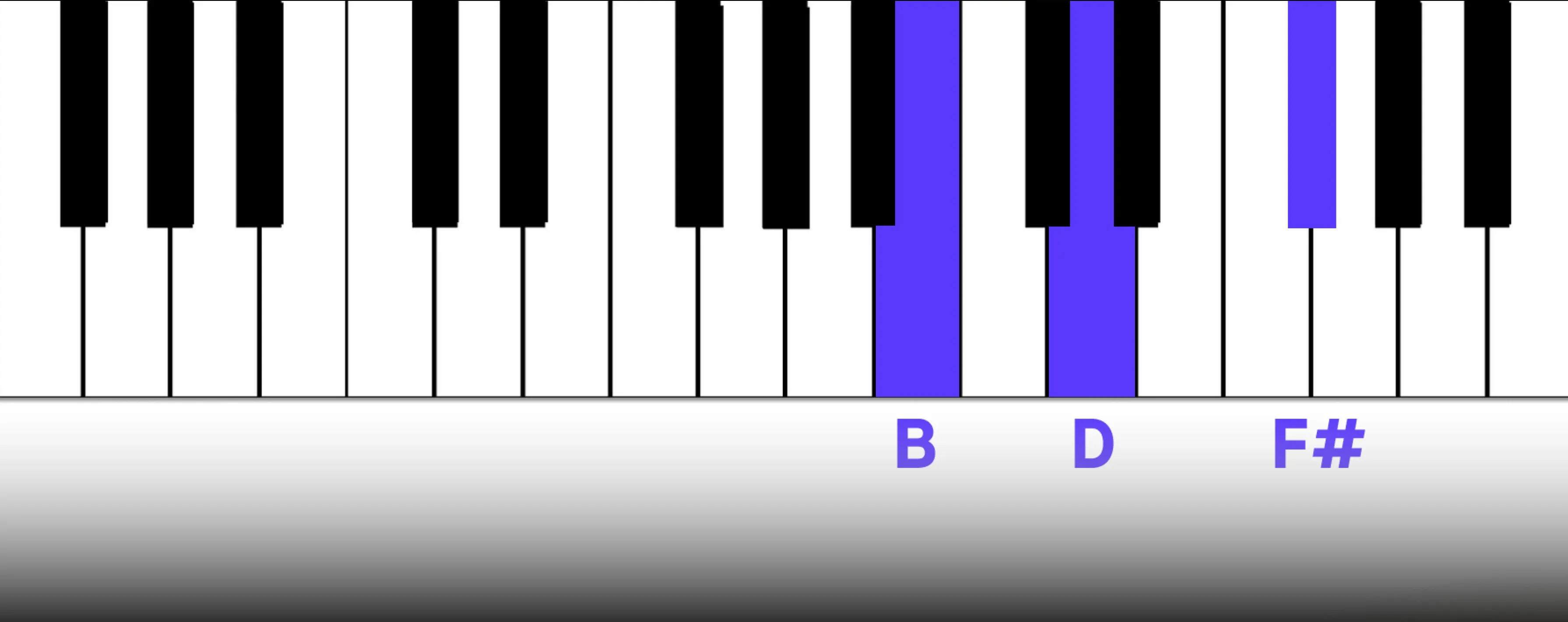

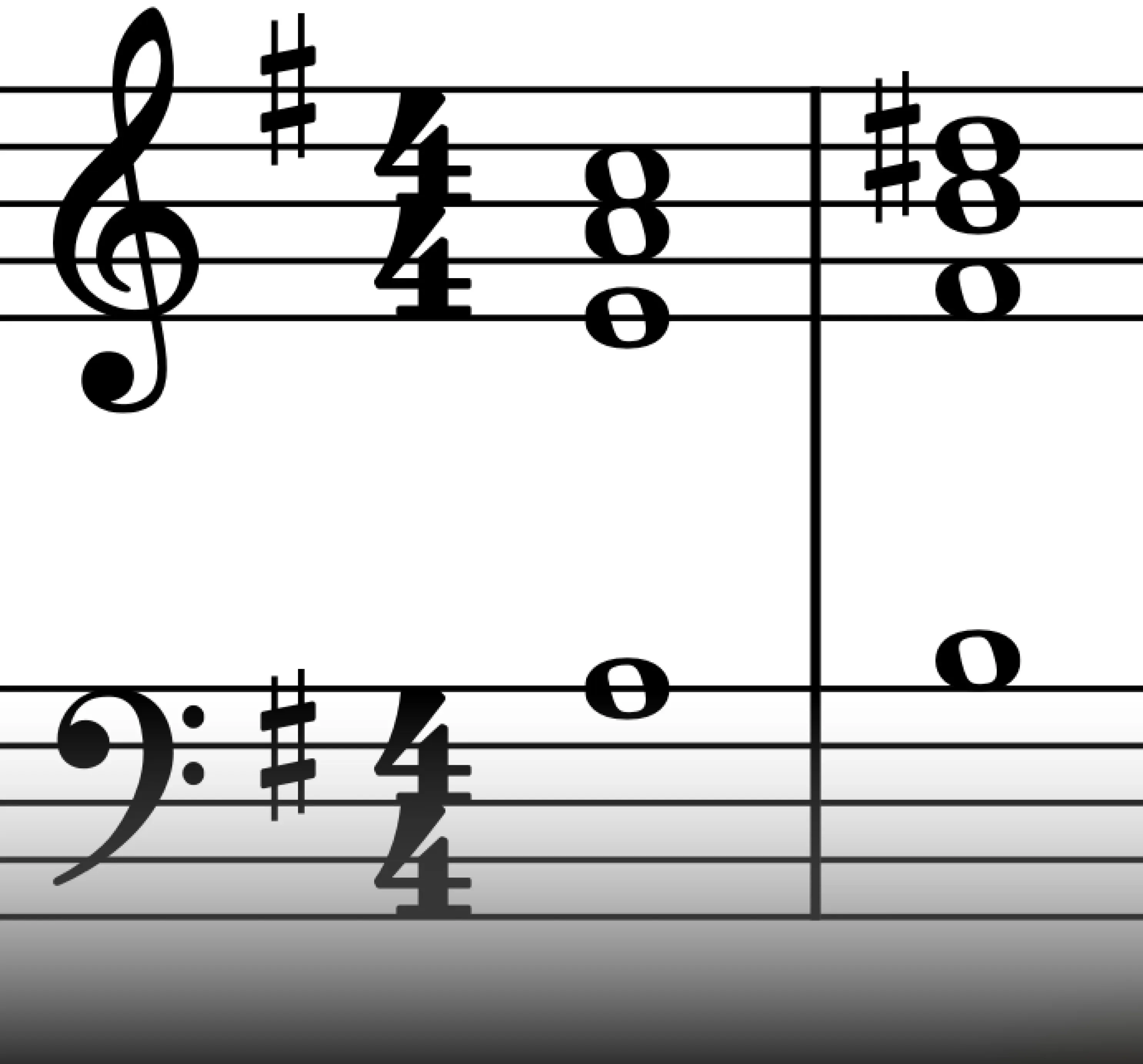

v/ V: B Minor/ B Major

The dominant chord's inherent dissonance, especially as a major chord, creates a strong pull towards the tonic. Adding a seventh to the dominant chord intensifies this tension, leading to a more powerful resolution. It's not uncommon for chord progressions to begin on the dominant, creating a powerful and energetic contrast with the preceding section.

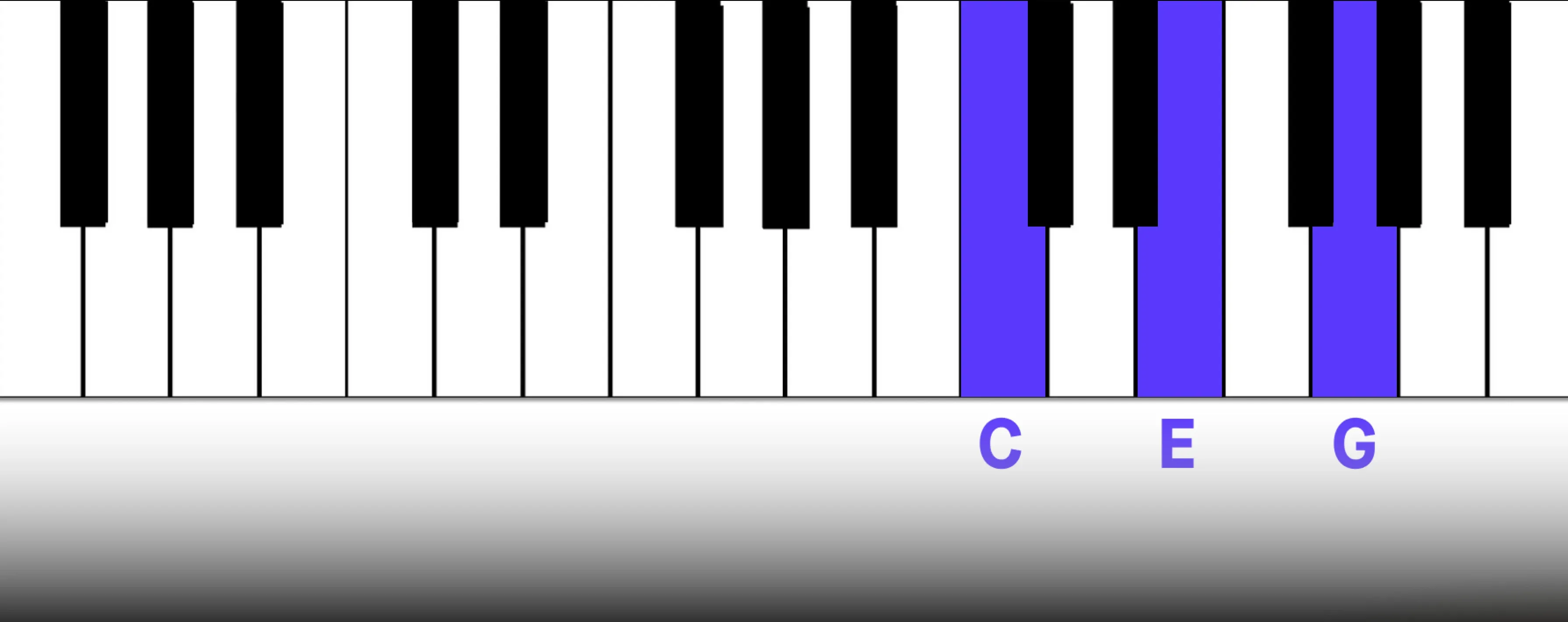

VI: C Major

The submediant chord offers a contrasting color, providing a sense of temporary resolution. This chord can also be used as a tonic substitute since the third in C major is the root of the tonic chord. For that reason, the VI chord can offer a sense of stability.

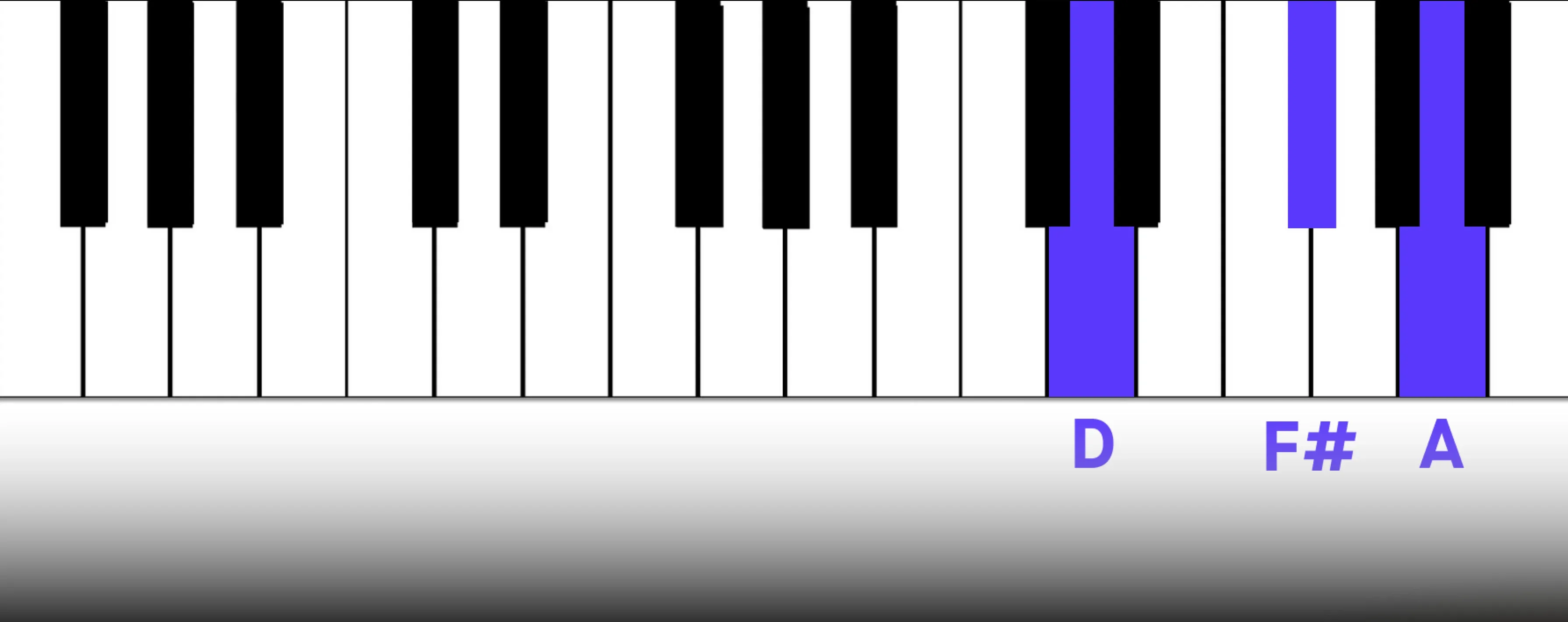

VII: D Major

The chord built on the seventh scale degree offers diverse harmonic possibilities. As a subtonic, it provides a natural resolution to the tonic chord. It’s frequently used as a passing chord to tie chords and phrases together. A more complex way of thinking about the VII chord is to view it as a secondary dominant of the relative major key. That gives it a dominant chord function, as well. We return to secondary dominants further down in the article.

Primary and Secondary Chords in E minor

Diatonic chords in E minor are categorized into primary and secondary chords.

- Primary chords - i, iv, and V - form the foundational harmonic framework of the key.

- Secondary chords (ii°, III, VI, and VII) add harmonic color and deeper interest to a chord progression.

Understanding Chord Relationships and Intervals

To truly grasp chord relationships and intervals, experiment with various chord combinations. Start with the tonic chord and explore the intervals to each diatonic chord. Additionally, experimenting with chord inversions will help you understand how they affect the sound and stability of each chord.

This process will help you expand your musical vocabulary, enabling you to instinctively select the right chord and inversion to achieve your desired sound. Instead of testing every chord combination, you'll develop a keen ear for harmonic possibilities and instinctively know which chord you're after when you write music.

To enhance your interval recognition skills you should associate them with familiar songs. We’ve written an article on Ear Training that offers a list of songs that feature each interval, both ascending and descending.

Cadences in E minor chord progressions

Cadences are musical punctuations used to end musical phrases or sections. Effective use of cadences is crucial for creating music with naturally occurring dynamics, movement, development, and interest. In spoken language, we can use exclamation points, question marks, periods, or cut-off mid-sentence to convey meaning. Cadences enhance the overall musical expression in your music. For example, saving the strongest cadences for key moments is a way to further increase their emotional impact.

In the following section, we'll delve into common cadences in E minor.

Perfect Cadence

Dominant → Tonic (V - i)

B → Em

The perfect cadence, a progression from the dominant to the tonic chord, is the most decisive and powerful cadence. It provides a strong sense of closure and is frequently used to end a piece of music. Using a dominant seventh chord before the tonic can heighten the impact of this resolution.

B7 → Em (V7 - i)

A perfect cadence requires two conditions: both chords must be in the root position, and the highest voice of the final chord must be the root note. When these conditions are met, the resolution is most powerful.

Plagal Cadence

Subdominant → Tonic (IV - i)

Am → Em

The plagal cadence, often called the “Amen Cadence”, provides a softer, more subdued conclusion than the perfect cadence. This cadence is commonly found in traditional hymns, often played to the final word “amen” hence its nickname.

Half Cadence

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (i / ii / iv → V)

Em→ B

F#° → B

Am→ B

A half cadence ends a phrase on the dominant chord. Unlike the definitive resolutions of perfect and plagal cadences, the dominant chord's inherent instability leaves the progression feeling incomplete.

By strategically using half cadences, you can manipulate expectations and create a sense of musical suspense and ambiguity.

Ending a bridge or pre-chorus on a dominant chord sets the stage for a satisfying resolution on the tonic chord at the start of the subsequent section, which significantly enhances the overall dynamic and emotional journey of your music.

Interrupted Cadence

Dominant to Submediant (V - VI)

B → C

An interrupted cadence initially suggests a strong, decisive resolution, but takes a surprising turn and concludes on the submediant chord. This cadence works well as a way to modulate to the relative minor from a major key.

Common Chord Progressions in E minor

In this section, we'll look at a few interesting chord progressions in E minor found in famous songs. We'll examine the strategic use of mediant and submediant chords as substitute tonic chords, and explore the nuances of various cadences, etc. Remember, a cadence is more than just a final chord progression. It's a deliberate musical punctuation mark that signifies the end of a musical phrase.

Let's explore common chord progressions in E minor.

i (Em) - VI (C) - III (G) - VII (D)

By using a tonic and two mediant chords in succession, the music maintains a familiar tonal center for an extended period. Both C major and G major can function as tonic substitutes, contributing to the tonal coherence of the first part of the section.

The major VII chord introduces the first significant tension, setting the stage for a return to the tonic. This exact chord progression is used in “Zombie” by The Cranberries.

i (E) - IV (G) - V (A) - VI (C) - VII (D)

This chord progression, as heard in Ed Sheeran's “You Need Me But I Don't Need You” is simple and minimalistic in its approach. The only secondary chord used is the major VII, which rounds off the progression well and sets up the tonic. By primarily relying on the primary chords, the progression maintains a sense of harmonic simplicity and natural tension. Sheeran's ability to create dynamic and expressive music with such a limited harmonic palette is a testament to his exceptional musicianship.

i (Em) - VII (D) - iv (Am) - VI (C) - VII (D)

This chord progression is characterized by its energetic, back-and-forth motion between chord intervals. This constant shifting, neither strictly ascending nor descending, creates a dynamic quality.

A great example of this is Avril Lavigne's “Take Me Away” where the progression propels the song forward with its lively and rather unpredictable nature.

i (Em) - III (G) - VI (C) - IV (Am)

This chord progression maintains a sense of tonal stability, avoiding the tension normally associated with the dominant chord. By minimizing harmonic shifts, the progression creates a continuous flow rather than a series of distinct beginnings and endings that you tend to get with V-I intervals, for example.

This approach is exemplified in Incubus' “Drive” where the smooth progression contributes to the song's relaxed and meditative atmosphere.

i (Em) - VII (D) - VI (C) - III (G) - V7 (B7)

This progression creates interest for two reasons: It begins with a dramatic leap from the tonic to the subtonic, immediately establishing tension that would typically resolve back to the tonic. Instead, the progression continues its downward movement; going to the VI and III chords. Finally, it ends up on a dominant 7 chord, which naturally anticipates resolution to the tonic.

This exact chord progression is found at the end of the verse in Metallica's “Nothing Else Matter” where it serves as a perfect setup for the powerful chorus.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

The Aeolian mode offers the basic framework for the natural minor scale. However, by also using chromatic notes, we can significantly expand our harmonic possibilities, creating more intriguing chord progressions.

Chromatic notes serve as the building blocks for creating diminished, augmented chords, and by incorporating them, we can change the quality of the diatonic chord for a more expansive harmonic palette.

Another way to add harmonic interest to the music is to modulate to the relative key signature.

Relative Major

The relative major

In a minor scale, the relative major is found on the third scale degree, the mediant. In E minor, that’s G Major.

The relative minor

The relative minor is found on the sixth scale degree, the submediant. In G Major, that’s E minor.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

When you modulate to G major you get a new tonal world with seven distinct diatonic chord functions, all within the same key signature. For more information about G Major, check out the article"Learn the Chords in G Major".

The close relationship between E minor and G Major allows for exciting harmonic exploration. This subtle tonal shift can add depth and create distinct emotional tonalities for different sections of a song. Modulating between relative keys is a common technique to prevent a song from becoming stagnant and keep it developing.

For instance, transitioning from E minor to its relative major, G major, can create a sense of uplift and energy. Conversely, moving to the parallel minor can evoke a more melancholic and somber mood.

Adding Complexity to E minor Chord Progressions

There are a few simple tricks to add harmonic interest to a song without modulating to different key signatures and changing the entire tonal center. What we’ll look at here are parallel chords and secondary dominants.

These techniques can quickly create dynamic shifts without disrupting the overall and established tonality of the song.

Parallel Chords

Parallel chords, created by altering the quality of a chord through accidentals, offer unexpected harmonic twists. For example, lowering the third of the mediant chord from B to B♭ in a chord progression creates an G minor chord, which has a distinct emotional impact compared to the diatonic major mediant.

The interval formed by a minor tonic and a minor mediant, known as a chromatic mediant, offers a distinctly dark and somber tone. To delve deeper into this powerful harmonic tool, check out our article on Dark Chord Progressions.

Furthermore, you can occasionally use the opposite quality for your tonic chord to create surprising emotional shifts within a phrase or section.

Remember to use parallel chords sparingly. Overusing them can cause the music to lose focus as it lacks a clear tonal center. By using them strategically, you can guide your listener on unexpected harmonic journeys while maintaining the song's overall tonal direction.

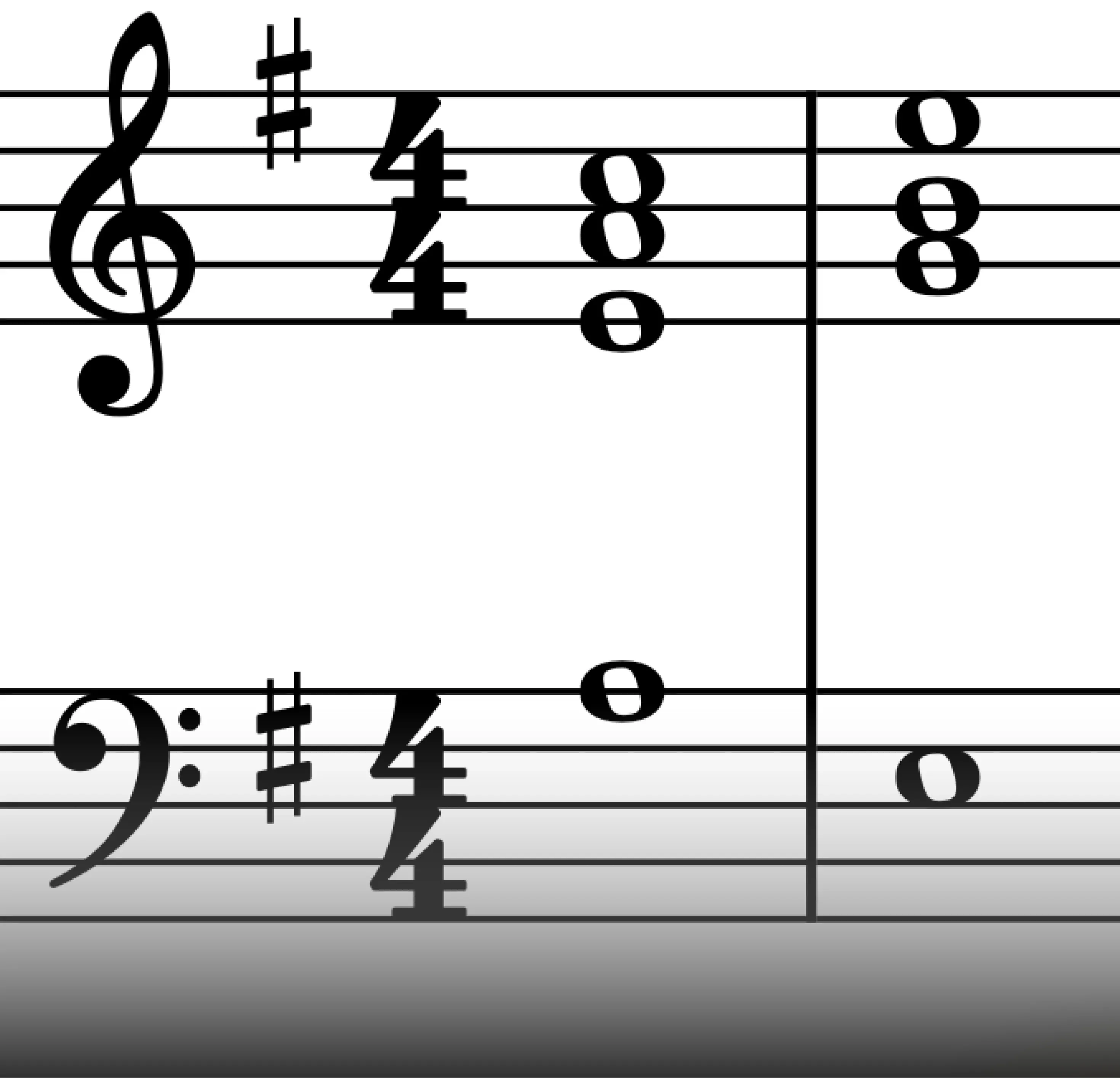

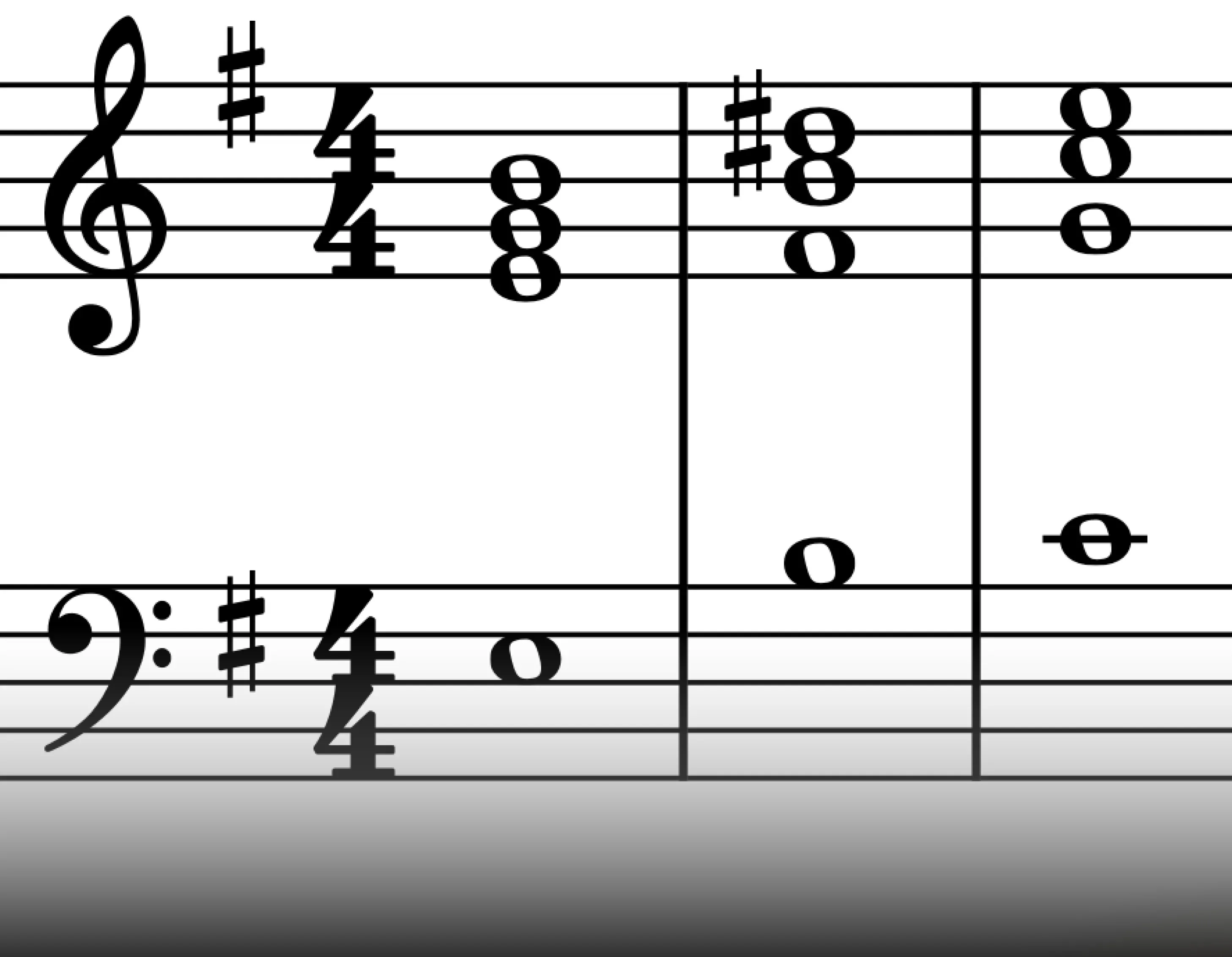

Secondary Dominants

A secondary dominant chord is a dominant chord borrowed from a key other than the main key of the song. It's a powerful tool for creating harmonic tension and resolution, while adding depth and complexity to chord progressions, making it more interesting.

A common type of secondary dominant chord is built on the fifth scale degree, often referred to as the"dominant of the dominant” (V/V) This involves treating the primary dominant chord as a temporary tonic and preceding it with its own dominant chord.

In E minor the dominant chord is B major. The dominant of B major is F# major. A chord progression using this secondary dominant would contain a F# major - B major chord progression.

Here’s an example of this:

i (Em) - V/V (F#7) - V (B7) - i (Em)

Even just a basic grasp of certain music theory concepts can instantly elevate your music production, composition, or songwriting. By understanding the relationships between chords and notes, you'll gain the power to craft more purposeful and emotionally impactful music.

How Musiversal Can Help You Write the Best Music

A solid understanding of music theory is invaluable when collaborating with Musiversal's talented musicians. This knowledge empowers you to effectively communicate your musical vision and ensure your ideas are accurately translated.

For example, including a V/ii in your chord chart signals the intent of a secondary dominant, guiding musicians' voice-leading decisions to connect chords.

If you need assistance writing compelling chord progressions or adding harmonic depth, our pre-production and songwriting experts are here to help.

With a Musiversal Unlimited membership, you gain unlimited access to a network of over 100+ professional musicians and award-winning engineers. Together, you can turn your musical dreams into reality.

Join The Musiverse: Your free space to connect, create, and compete.

Collaborate with global creators, level up in live workshops, and win exclusive prizes. Join the community today!

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist