Learn the Chords in G Major: A Music Theory Resource

Master the G Major Key: Discover essential chords, useful progressions and techniques to elevate your music production and composing skills.

Introduction

A solid grasp of even fundamental music theory concepts can quickly improve your songwriting as music producers and composers. By understanding the building blocks of harmony, such as diatonic and chromatic chords, scales, and intervals, you'll gain the ability to write interesting and captivating chord progressions without having to do the guesswork of what will sound good.

In this comprehensive guide, we dive deep into the G Major key signature. You’ll learn how to:

- Identify diatonic chords: Discover the 7 fundamental chords of G major and how to use them to create interesting and engaging chord progressions with tension and resolution.

- Explore interesting progression in G major: We’ll look at famous examples of songs in G major and the chords they use to invoke certain emotions and propel the song forward.

- Use modal interchange: Learn a couple of advanced techniques like secondary dominants, parallel chords, and relative key signatures to add depth and complexity to your music.

By the end of this guide, you’ll have a deeper understanding of music theory and the tools to compose more sophisticated music.

The Basics of G Major

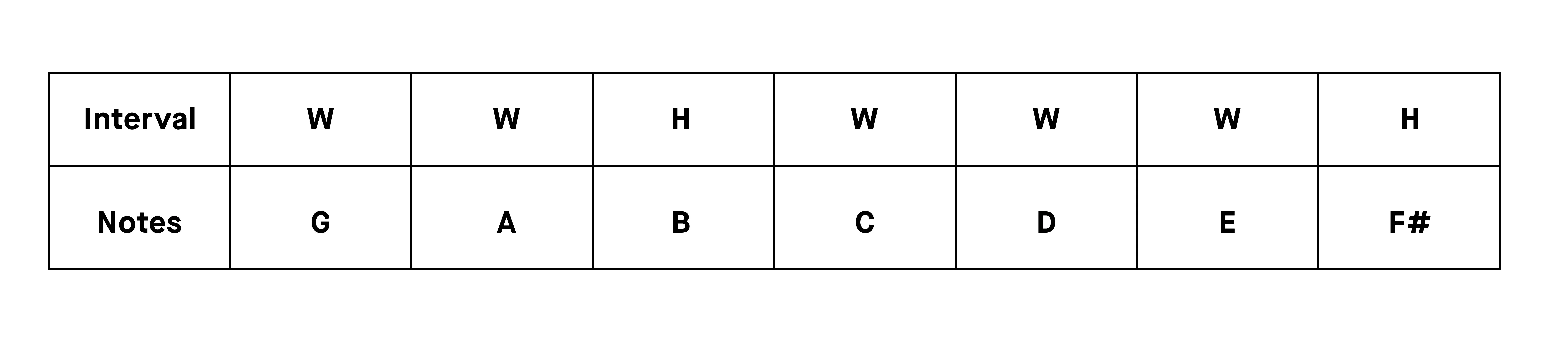

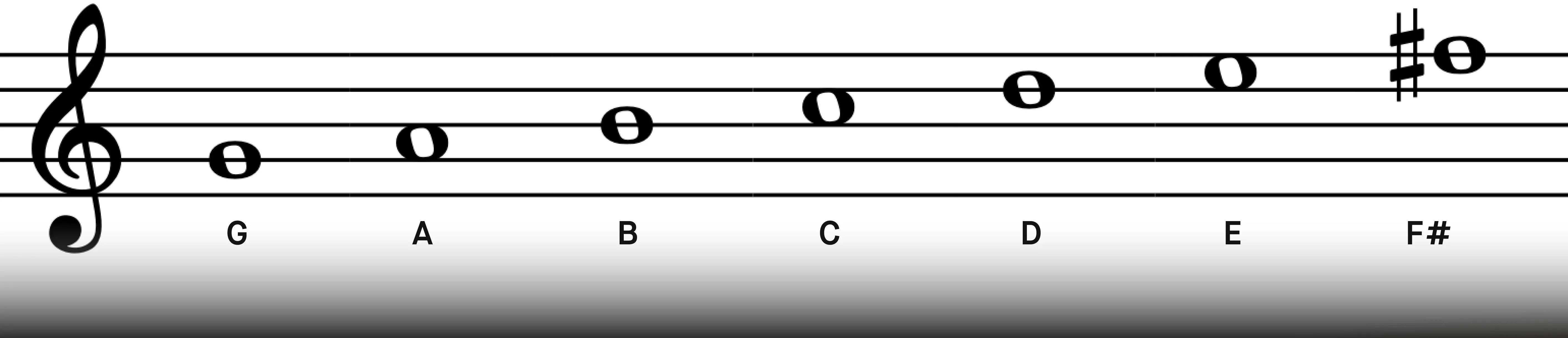

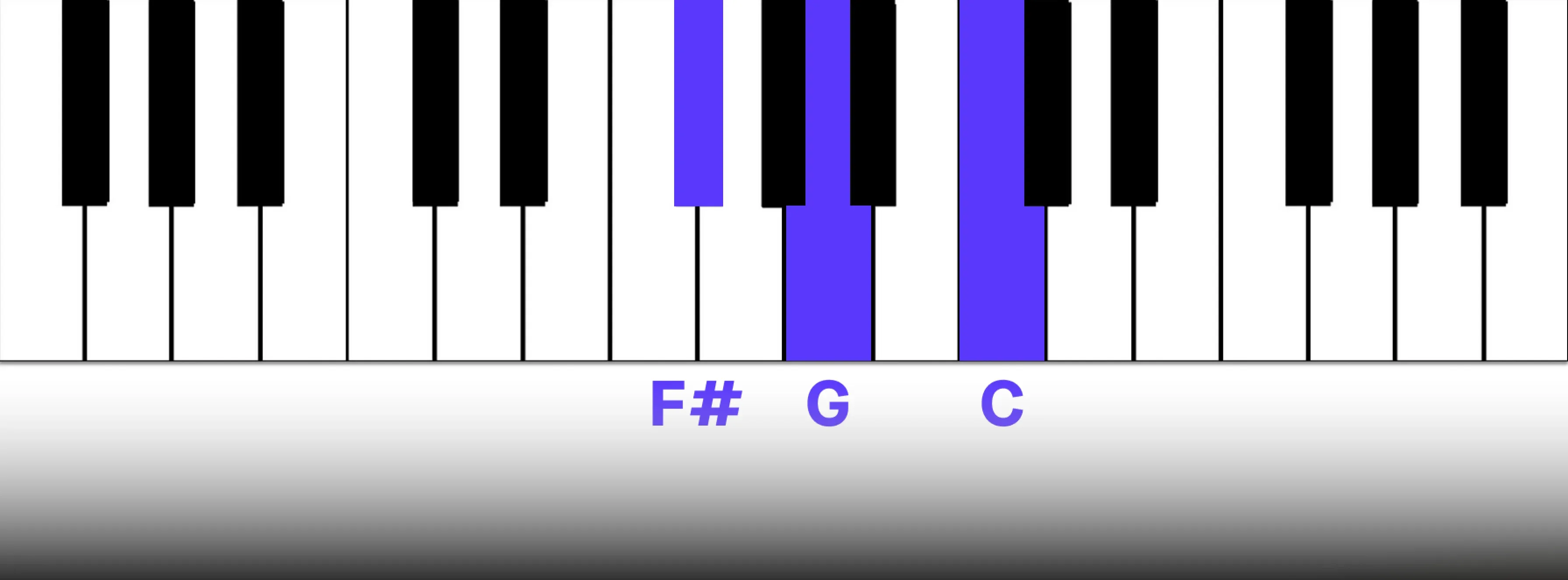

The G Major scale is the most common phrase to refer to the Ionian mode, which is made up of the following note pattern - starting on the note G:

Each note within a scale occupies a specific position, known as its scale degree. This degree directly correlates with the harmonic function of the note, determining its role within a key. In the G major scale, each note holds a distinct scale degree, highlighting its connection to the tonic note G.

- G - Tonic

- A - Supertonic

- B - Mediant

- C - Subdominant

- D - Dominant

- E - Submediant

- F# - Leading Tone

The seven scale degrees serve as the building blocks for the diatonic chords within the key signature, each with a unique harmonic function. One way to think about function is the chord’s sense of stability or instability in relation to the tonic.

For example, the G major chord, functioning as a dominant chord in the key of C major, is inherently unstable, creating tension that needs to be resolved. However, as the tonic chord in the key of G major, it provides stability and resolution.

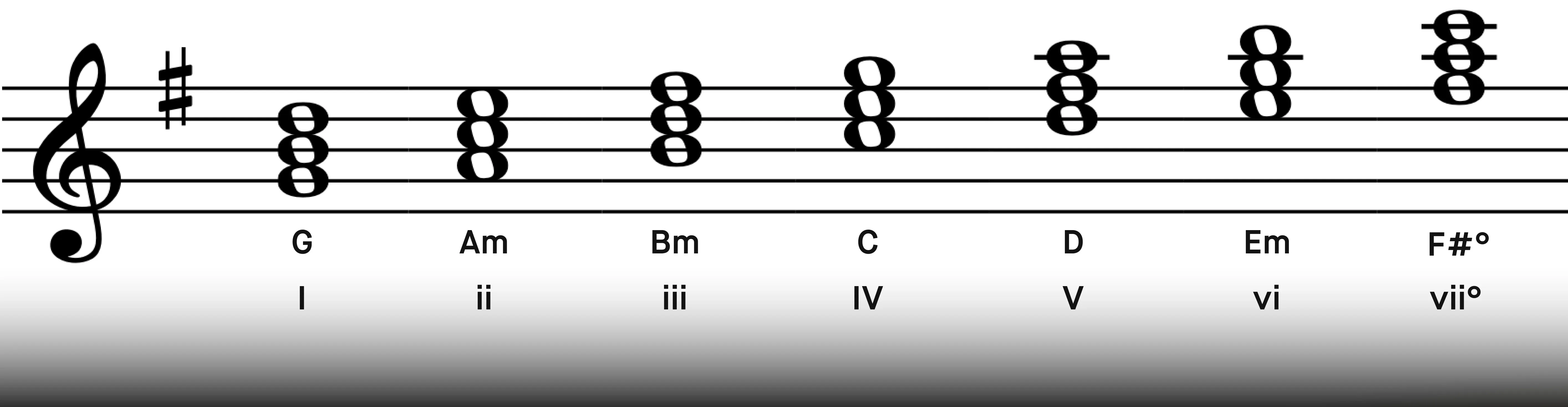

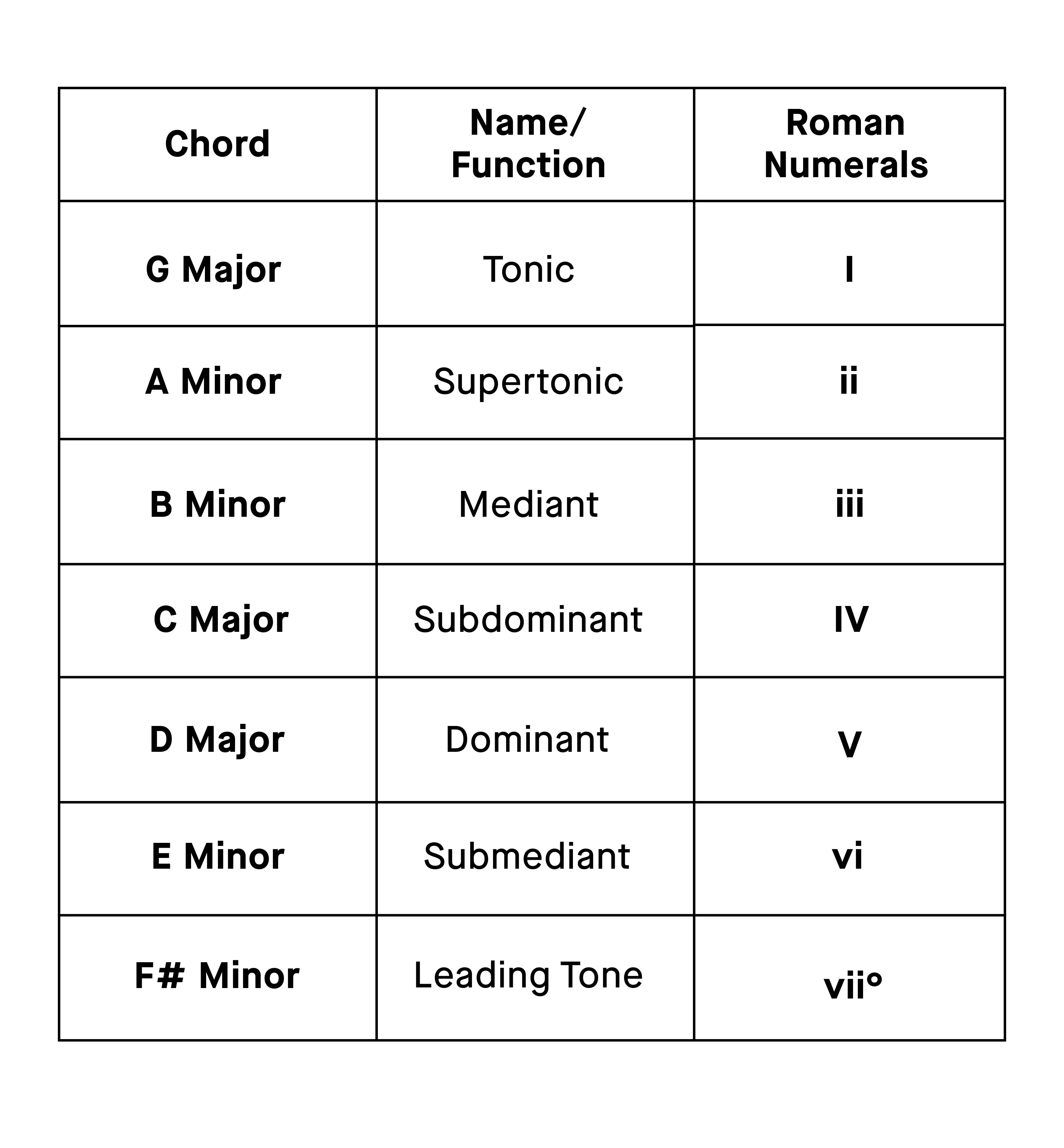

To indicate both chord function and quality (major or minor), Roman numerals are used. Uppercase Roman numerals represent major chords, while lowercase numerals are minor chords. The numeral itself suggests the chord's scale degree and harmonic function. For instance, the I chord represents the tonic chord, the most stable chord within a key, while V symbolizes the dominant chord, which generates tension. Roman numerals provide a key-independent framework for understanding and communicating harmonic structure and function in music.

Regardless of the specific key signature, a V chord consistently generates tension and seeks resolution to the tonic chord. Thus, the V chord has a dominant chord function.

This system allows you to convey harmonic ideas and functions without being confined to specific chords. The I-V interval keeps its inherent quality, regardless of the key, whether it's G Major, C Major, Bb Major, or any other key.

The notes that naturally occur based on the Ionian scale pattern starting on G form the foundation of the G major key signature and are referred to as diatonic notes. The remaining notes, called chromatic notes, are useful for adding harmonic richness, depth, and unpredictability to chord progressions. However, it's important to use them carefully and with intention to avoid sounding like a mistake. Learning how to incorporate and approach non-scale tones into your music is a powerful tool to elevate the depth and interest in your melodies and chord progressions.

The chromatic notes are also useful for creating tension, modulating to different keys, or simply altering the quality of diatonic chords, a technique we will explore further in the section"Adding Complexity to G Major Chords."

When a diatonic note is altered, it is referred to as an accidental. These alterations are indicated by sharp (♯) and flat (♭) symbols. To restore a note to its original diatonic pitch, a natural (♮) symbol is used.

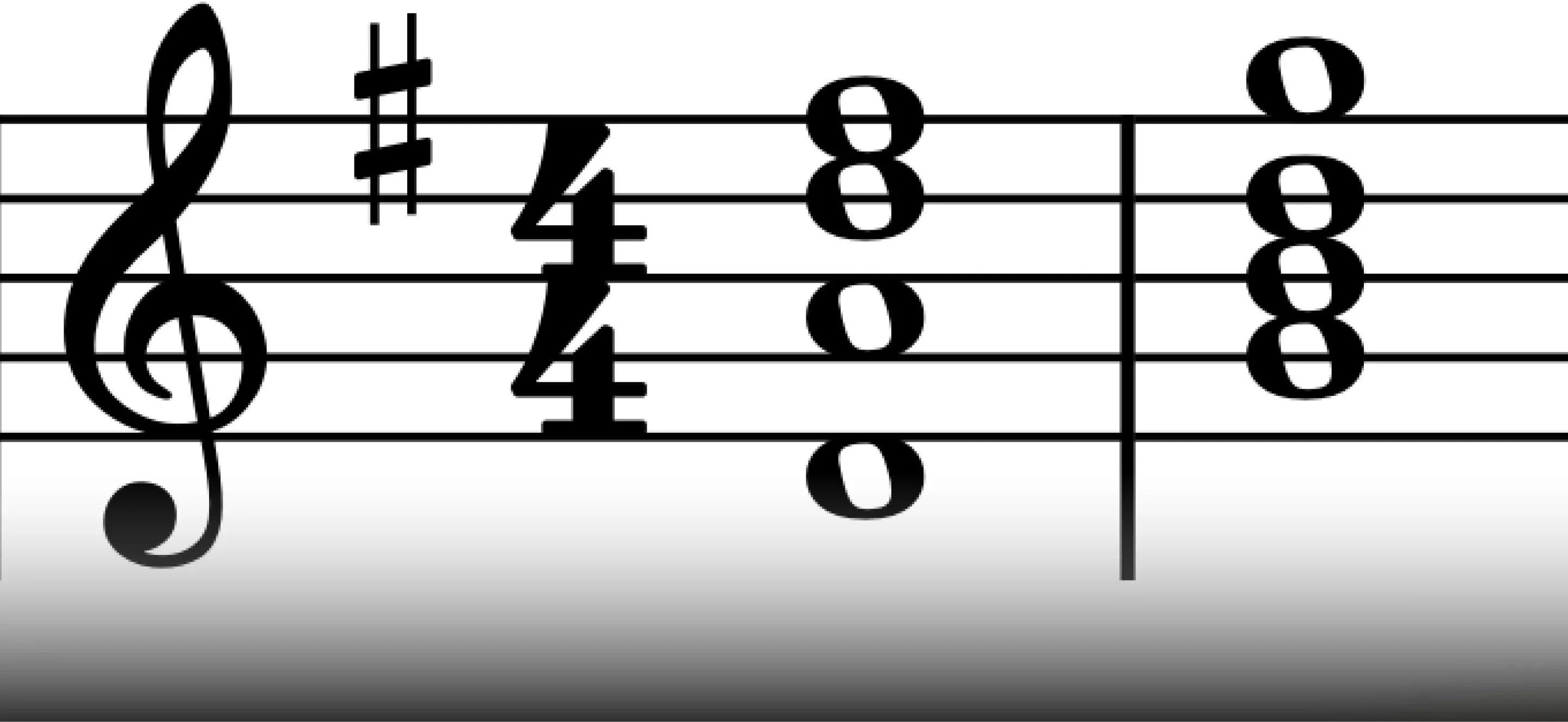

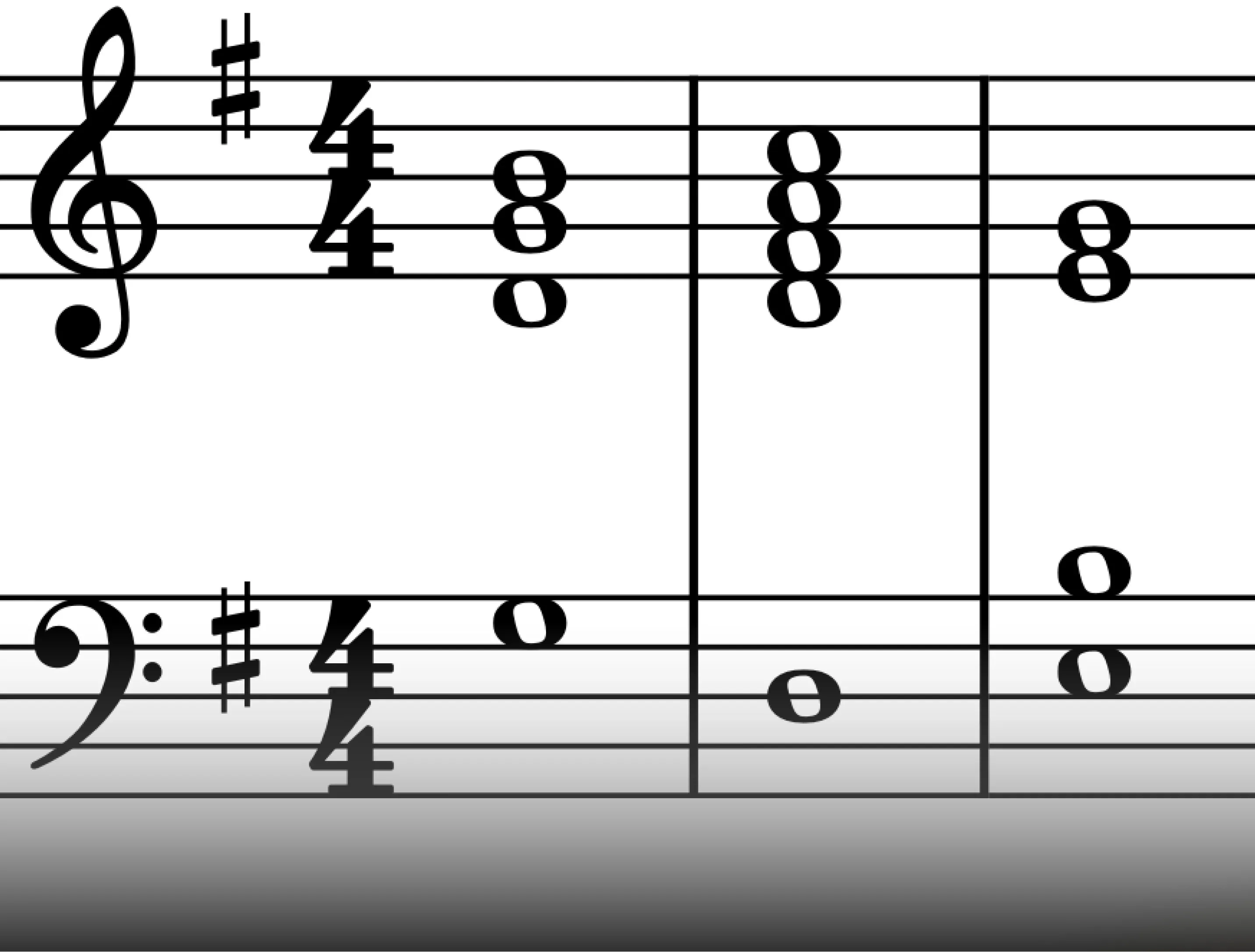

Chords in G Major

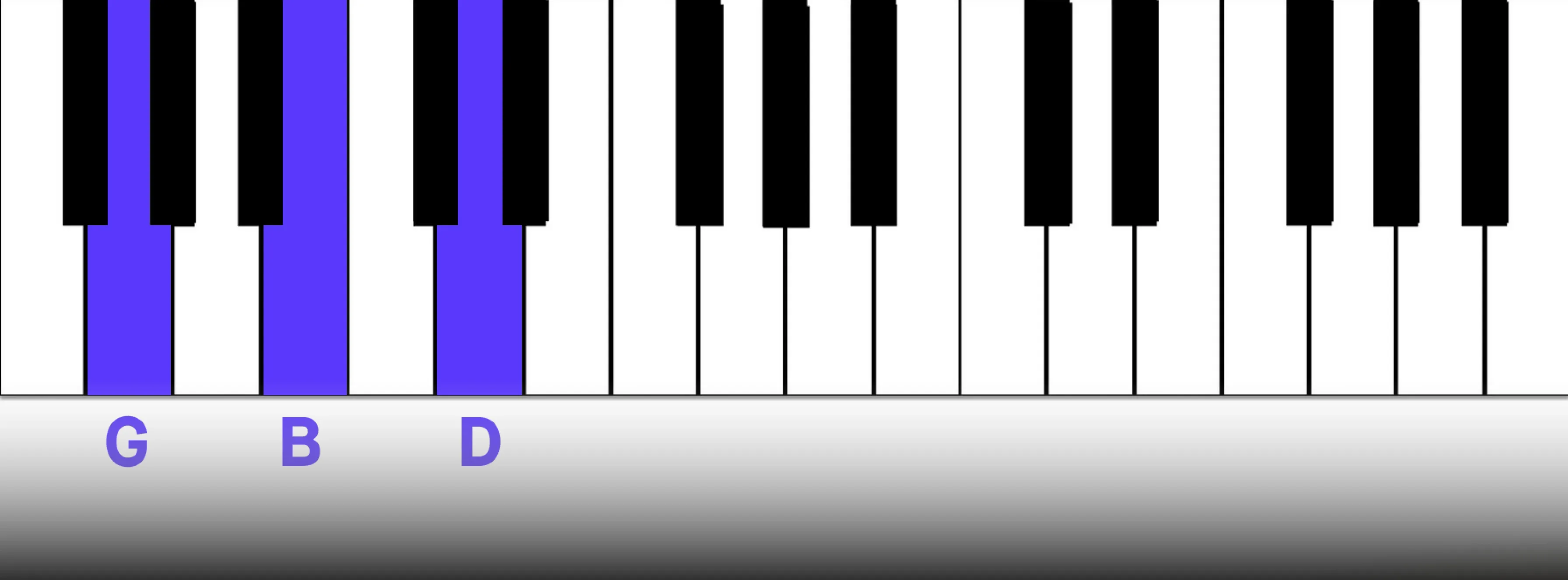

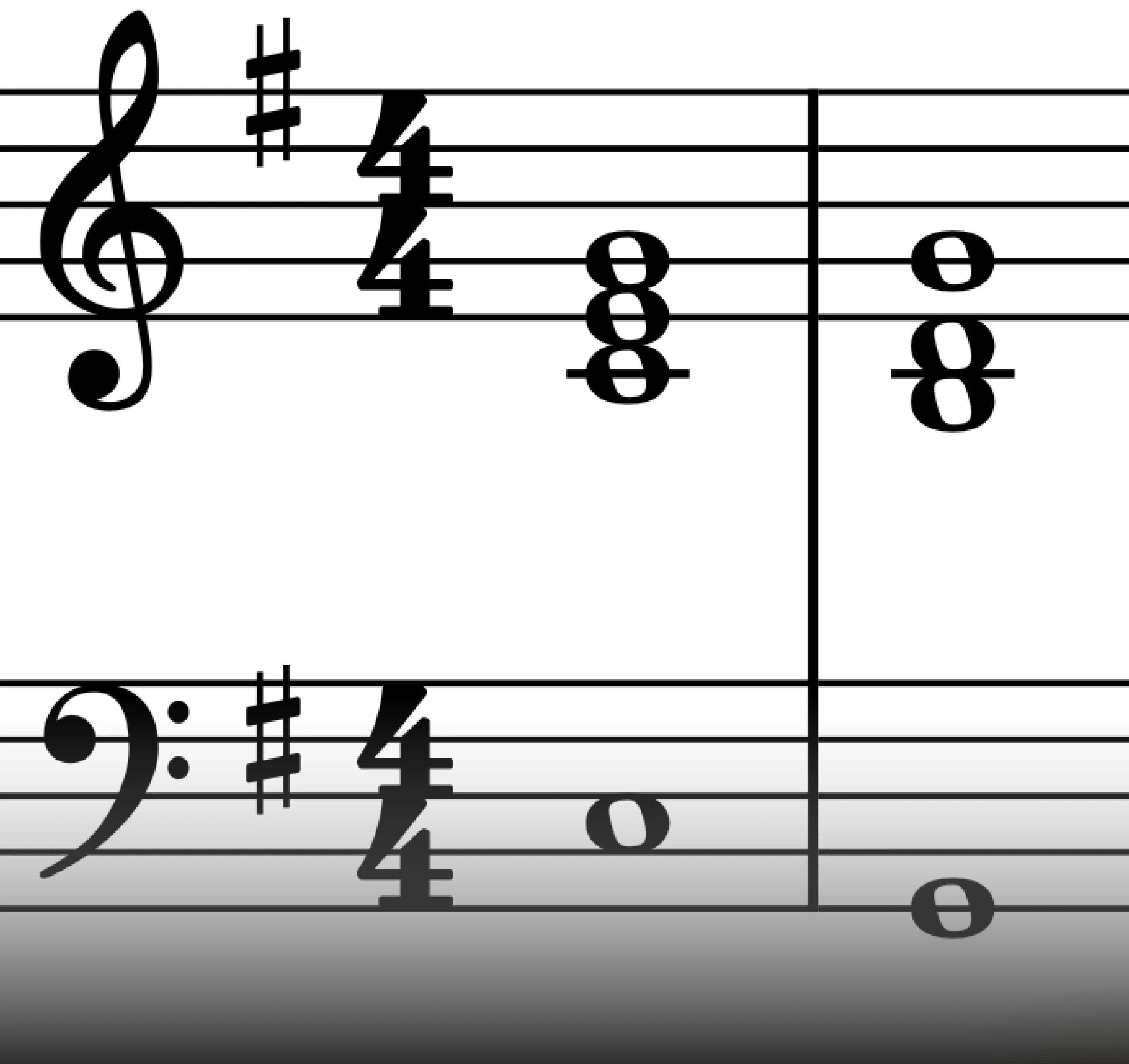

I: G Major

G Major serves as the tonic of the entire scale, providing stability, resolution, and a sense of rest. Unlike the other chords within the key signature, the tonic chord does not to move to any other chord, thus contributing to its inherent sense of rest and stability.

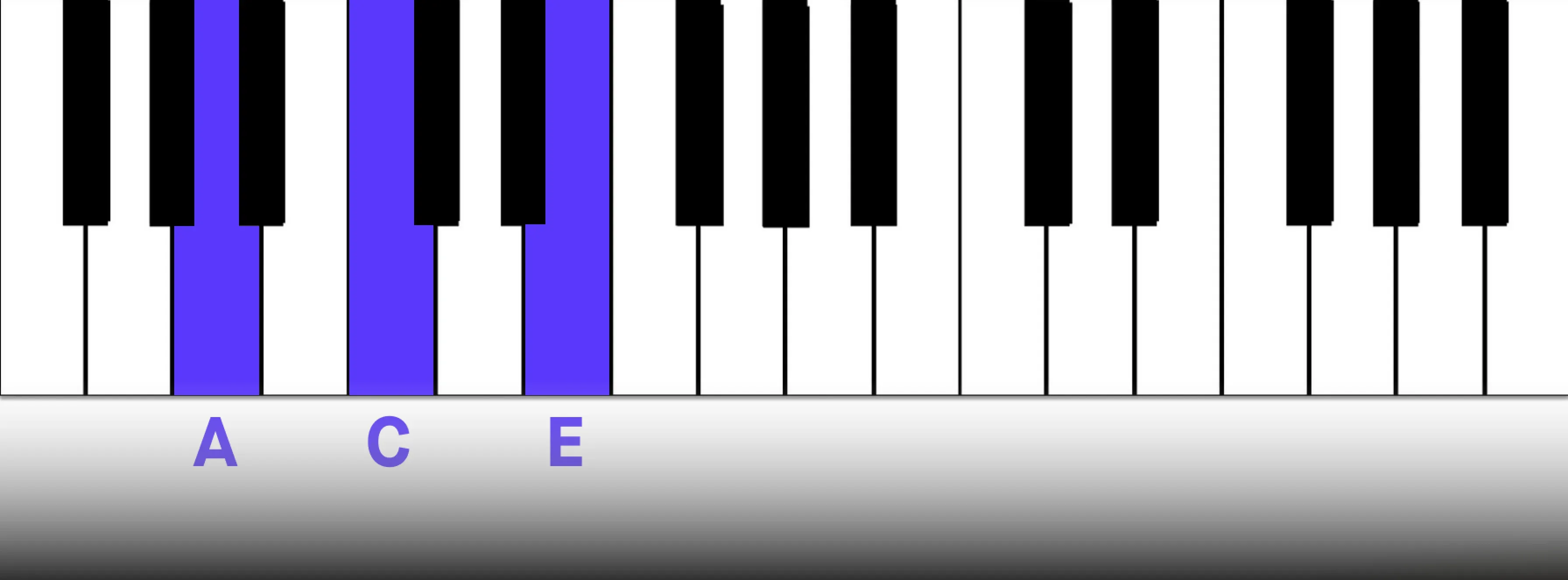

ii: A Minor

The supertonic function of the ii chords can lead both to and away from the tonic - depending on the context of the harmony and chord progression. Leading away from the tonic, it tends to move to the dominant, giving it a subdominant function. The most common jazz chord progression is the ii-V-I which starts on the minor ii chord.

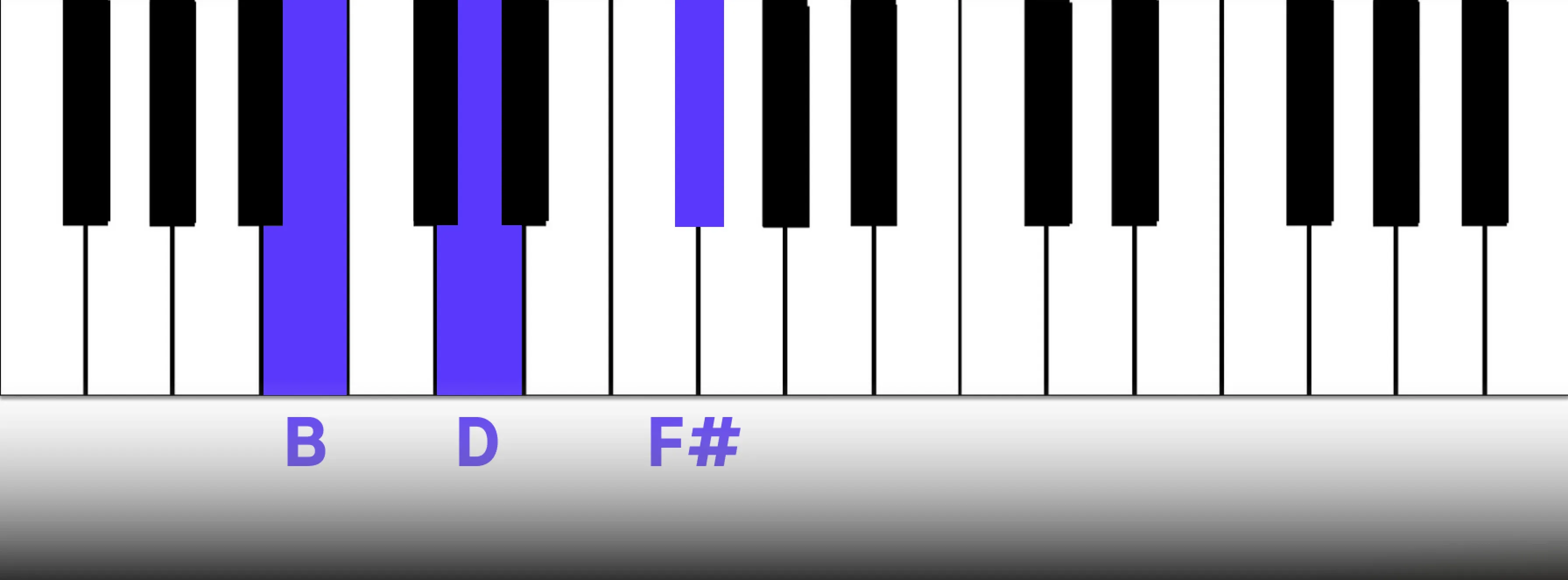

iii: B Minor

There's a tonal similarity between the I and iii chords despite their opposite chord qualities. They share two notes, which gives the mediant chord (iii) a tonic function, allowing a chord progression to rest there.

While less defined than the primary tonic chord, it still works well for stability. A strategic use of tonic substitutions is a great way to add dynamic movement and heighten the impact of the tonic chord when used for resolution.

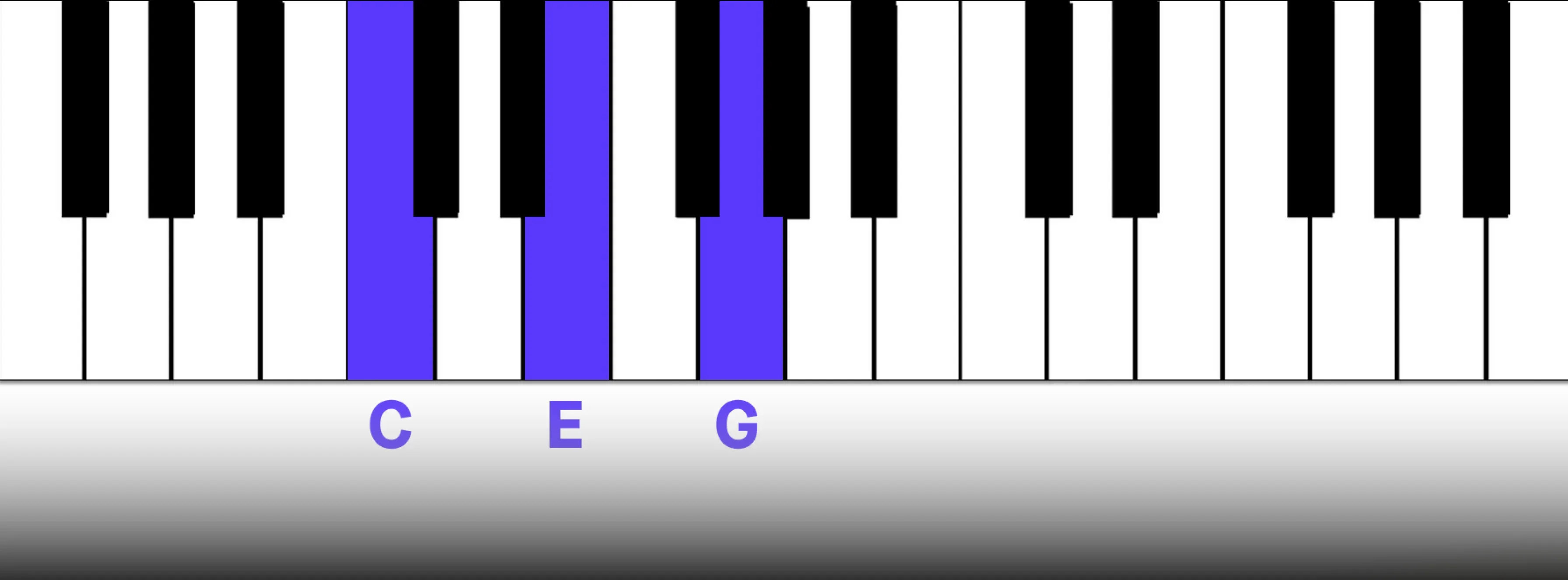

IV: C Major

The subdominant chord is a versatile chord that can offer both harmonic contrast and anticipation. An IV-V interval will further increase the tension. It’s one of the most common intervals in western music.

V: D Major

Together with the tonic, the dominant chord is the most important chord in any key signature. It creates tension and strongly pulls towards the tonic. The third degree of the dominant chord is only a half-step away from the tonic, further intensifying this pull towards resolution.

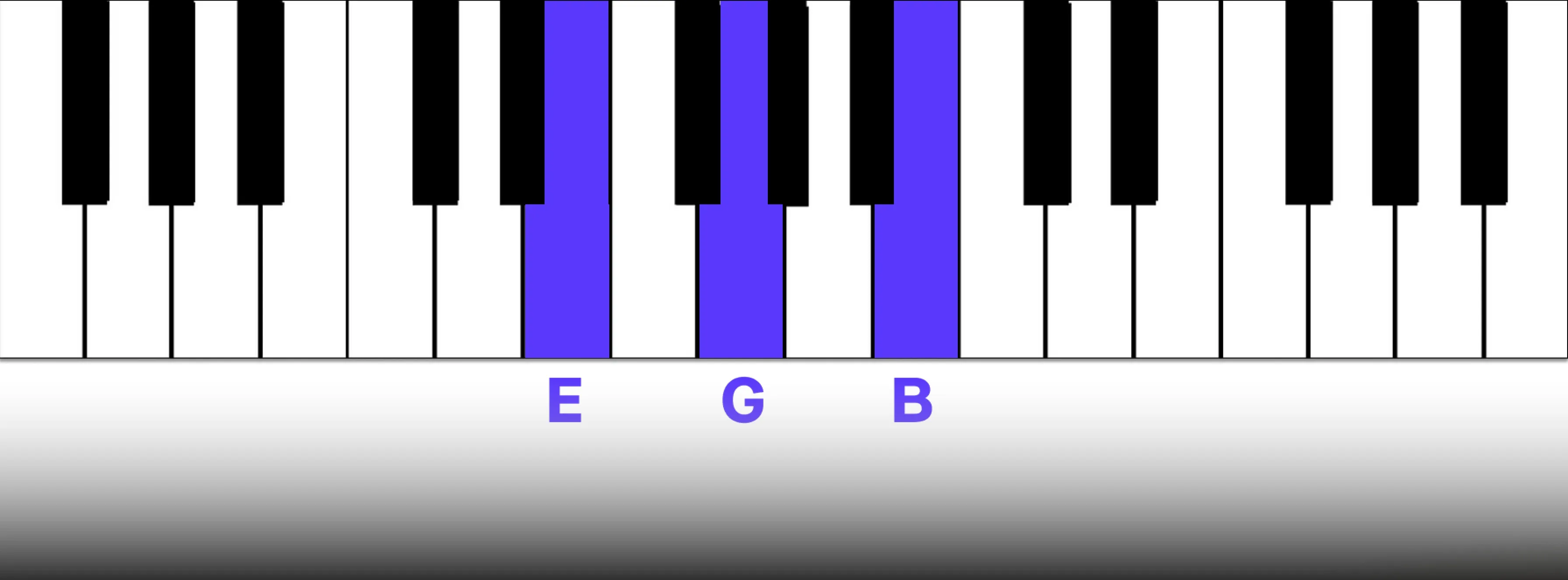

vi: E Minor

The submediant chord can also function as a substitute for the tonic chord and offer a sense of stability in the opposite quality to the tonic. The submediant chord is also the tonic of the relative minor key, which makes the minor vi chord a great destination for modal interchanges. We’ll return to this topic later.

vii°: F# Diminished

Diminished chords contain an interval of a tritone, making the chord unstable. In a major key, it has a leading-tone function, meaning the most natural progression is to resolve to the tonic.

Primary and Secondary Chords in G Major

Chords are divided into two categories: Primary chords and secondary chords.

- Primary chords - I, IV, and V - these chords for the harmonic foundation of the key signature.

- Secondary chords (ii, iii, vi, and vii°) add a specific harmonic flavor and deeper interest to a chord progression.

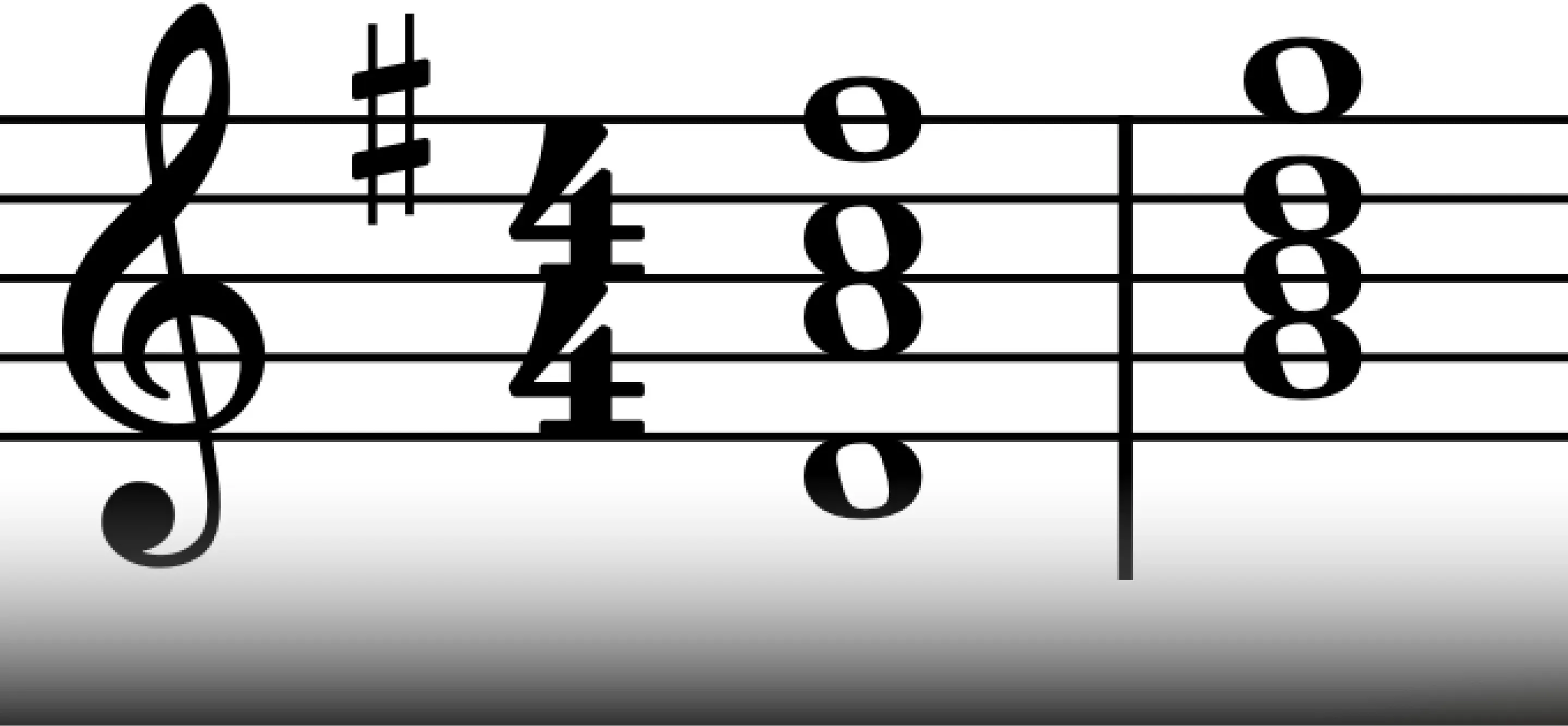

Understanding Chord Relationships and Intervals

Experiment with various chord intervals and combinations to get a good sense for the harmonic and tonal relationship between any two diatonic chords. On top of this, it’s crucial to also work with chord inversions, since this will change the sound of a chord and voice-leading possibilities. A chord's perceived stability can shift depending on its inversion. A tonic chord with the 5th or 3rd in the bass can function as a subtle tonic substitute, offering a less definitive sound compared to the root position tonic. This can be a useful tool for creating harmonic interest and unexpected twists in a musical piece.

By practicing different chord intervals, you'll expand your musical vocabulary, enabling you to efficiently find the best chord for your musical intentions. This skill will save you time by eliminating since you’ll reduce testing of countless chord combinations to find the right one. Instead, you'll develop a good ear for all the harmonic possibilities, allowing you to intuitively choose the right chord.

Practice single-note intervals with the help of our guide on Ear Training. The best way to recognize intervals is to associate them with known songs. In our comprehensive article, we’ve found several examples of both ascending and descending of all intervals in western music tradition.

Cadences in G Major chord progressions

Cadences are the musical equivalent of punctuation marks. They signal the end of musical phrases or sections, shaping the overall flow, structure, and dynamics of a piece of music. Just as periods, commas, and exclamation points add nuance and emphasis to language, cadences provide musical punctuation, guiding the listener's ear and creating a sense of resolution, anticipation, or ambiguity.

By strategically placing strong cadences at key moments, you can heighten the emotional impact of your music.

In the next section, we'll delve into common cadences within the G Major key.

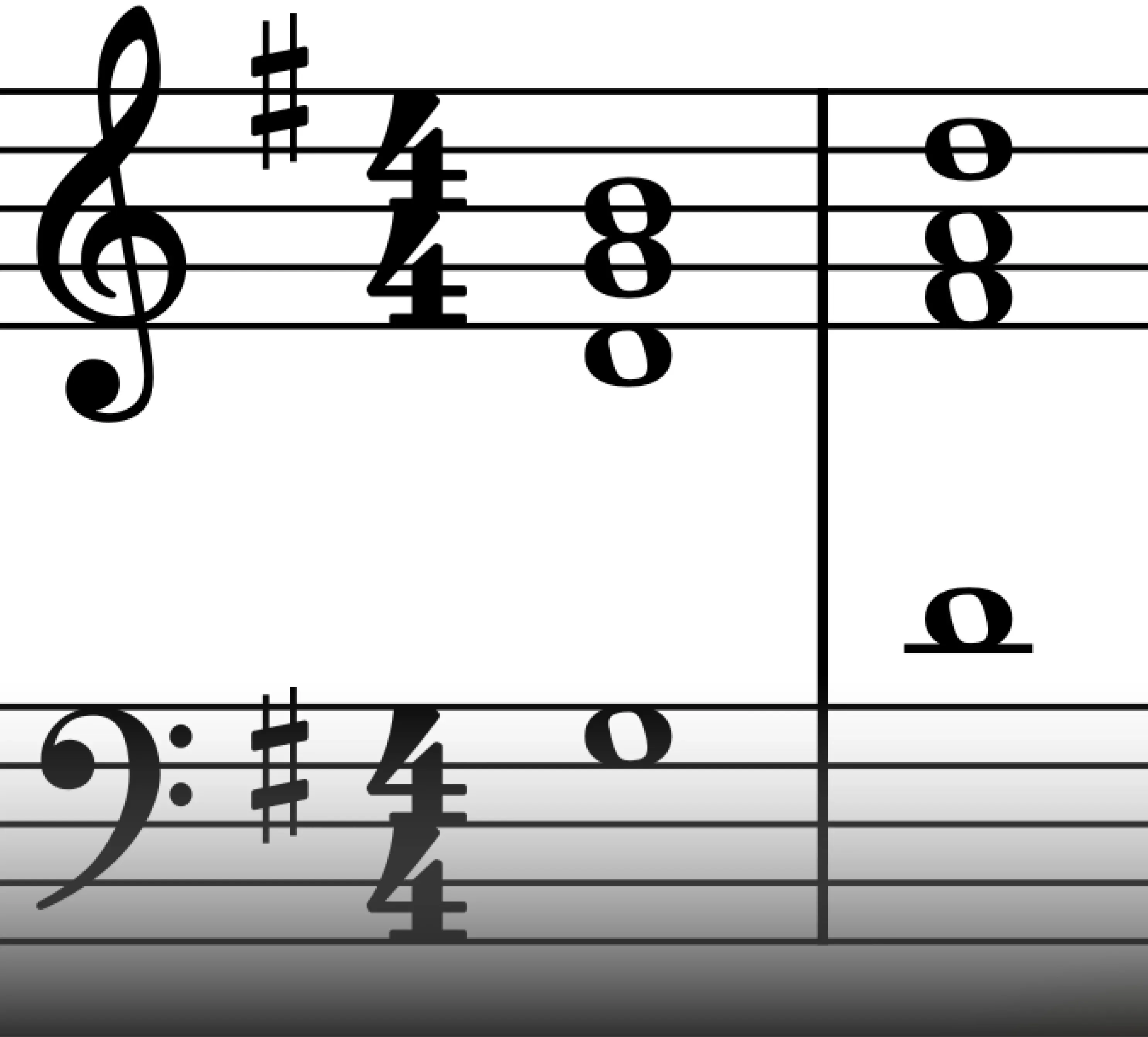

Perfect Cadence

Dominant → Tonic (V - I)

D → G

The perfect cadence, a progression from the dominant to the tonic chord, is the most powerful and definitive cadence. It offers a sense of closure and finality. A lack of a perfect cadence at the end of a song can leave the listener uncertain about whether the piece has truly concluded.

Using a dominant seventh chord before the tonic will further increase the tension of the dominant chord, making the resolution and its emotional impact even stronger.

D7 → G (V7 - I)

Both chords in a perfect cadence must be in root position. Additionally, the top voice of the final chord must be the root note of the tonic chord.

Plagal Cadence

Subdominant → Tonic (IV - I)

C → G

The plagal cadence, often referred to as the"Amen Cadence"offers a more subdued conclusion compared to the perfect cadence. This cadence is often found at the end of traditional hymns that conclude with the words"Amen"- thus its nickname.

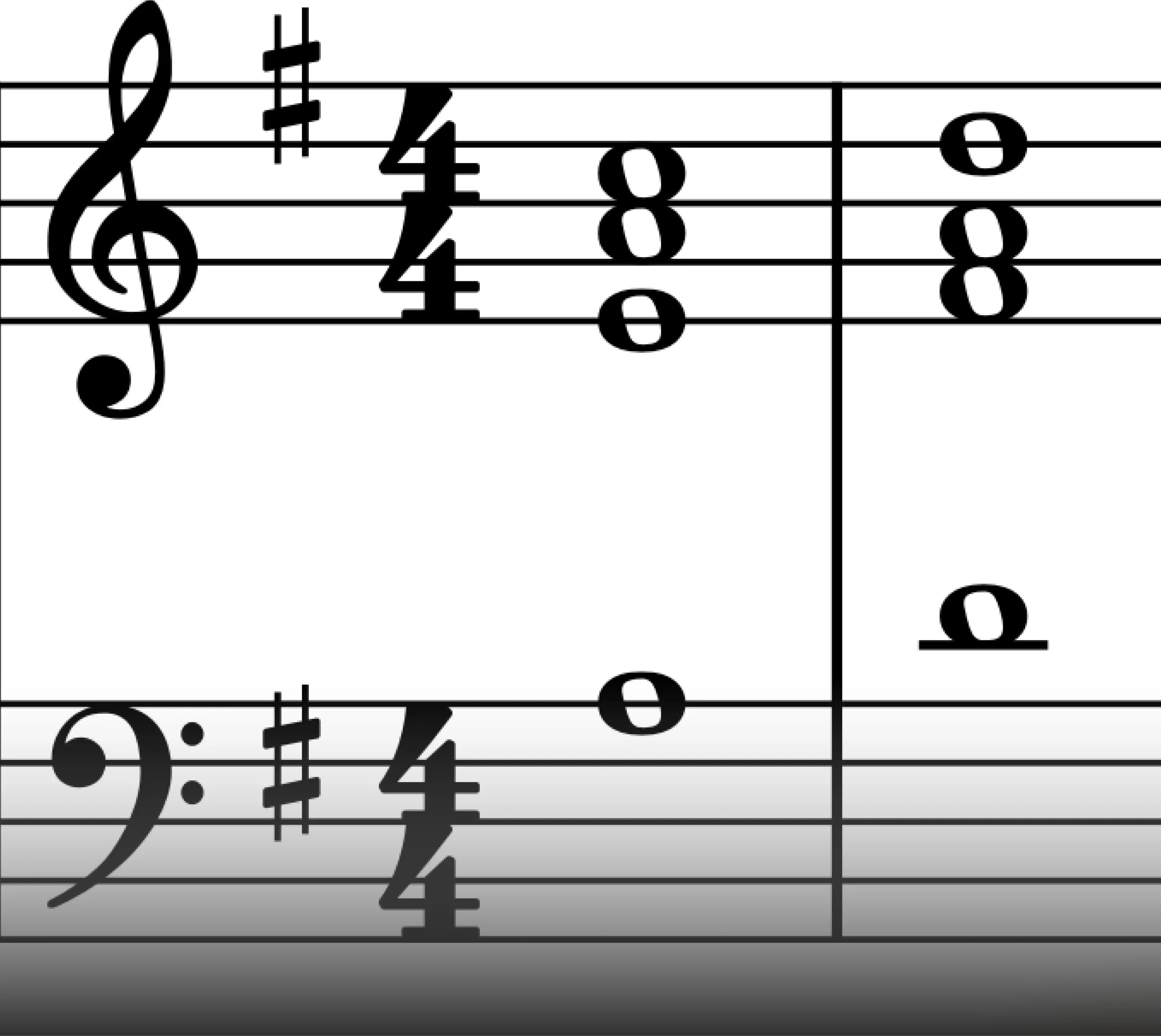

Half Cadence

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (I / ii / IV → V)

G→ D

Am → G

C → D

A half cadence completes a musical phrase on the dominant chord. Unlike the definitive resolutions of perfect and plagal cadences, the dominant chord's inherent instability leaves the progression feeling unresolved. For example, ending the bridge section or the pre-chorus on a dominant chord sets up for a powerful tonic to start the subsequent section of the song. This can significantly enhance the overall dynamic of your music.

Interrupted Cadence

Dominant to Submediant (V - VI)

D → E

Interrupted cadence appears to be heading towards a definite and strong resolution, but instead typically ends on the submediant chord. In a minor key, this can create energy. This cadence can also facilitate a modulation to the parallel key.

Common Chord Progressions in G Major

In this section, we'll delve into some interesting chord progressions in G Major, found in famous songs. We'll examine the strategic use of mediant and submediant chords as substitute tonics, and the nuances of various cadences. Remember, a cadence is more than just a final chord progression. It's a deliberate musical punctuation mark that signifies the end of a musical phrase or section, guiding the listener's ear and shaping the overall structure of the piecese.

Let's explore common chord progressions in G Major:

I (G) - V (D/F#) - vi (Em) - IV (C) - V (D)

This chord progression is one of the most widely used in modern pop and rock music. It creates an ideal balance of tension and release, with the minor vi chord adding a touch of melancholy and emotional depth. A notable example of this progression in G major is Avril Lavigne's "When You're Gone".

Its popularity makes the progression highly predictable, which is why it feels so natural and comfortable to listeners.

IV (C) - I (G) - V (D) - vi (Em)

This progression is a great example of how much can be achieved using just primary chords and a single secondary chord. While it shares the same chords as the previous example, it begins on the IV chord instead of the tonic, creating a fresh harmonic approach.

Starting on the IV chord is an effective way to introduce a sense of movement and tension right from the beginning. Taylor Swift's "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together", uses this exact chord progression to create an engaging, memorable harmonic foundation.

I (G) - V (D) - vi (Em) - IV/IV (F) - IV (C)

This chord progression, featured in "Free Bird" by Lynyrd Skynyrd, starts with a simple structure but becomes more complex by borrowing a chord from the C major scale. The F major chord functions as a subdominant, leading smoothly to C major, which temporarily takes on a tonic function.

This technique is known as the use of secondary chords. The F major chord acts as the subdominant, setting up a IV-I resolution within the key of C. This shift adds a sense of harmonic lift and unexpectedness, enriching the progression and enhancing its emotional impact by introducing a brief change in tonality. We’ll return to secondary chords further down in the article.

I (G) - V (D) - ii (Am) - IV (C) - V (D)

What sets this progression apart from previous examples is the use of the minor ii chord as the primary minor harmonic color. Unlike the submediant chord, which can sometimes function as a tonic and provide a sense of rest and resolution, the minor ii chord typically creates a sense of instability and a strong desire to resolve to the dominant. In this case, instead of resolving to a dominant chord, the ii minor leads to another chord with a subdominant function, which further amplifies the tension.

A great example of this progression can be heard in Oasis' "Live Forever".

By omitting the final dominant chord, we get the chord progression from “Hot N’ Cold” by Katy Perry and “Banana Pancakes” by Jack Johnson

I (G) - iii (Bm) - IV (C) - V (D)

Generally, the minor mediant chord doesn’t have the same functional weight as other minor chords in the key. Instead, it prolongs the tonic tonality sense of rest that the I chord provides. The interval of the tonic to the mediant is distinctive and often used in cinematic contexts. In Elton John’s “Crocodile Rock”, use this chord progression to create an effect and with a high degree of energy.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

While the Ionian mode provides a fundamental framework for the natural major scale, the incorporation of chromatic notes significantly expands our harmonic palette, allowing for the creation of more intriguing and complex chord progressions.

Chromatic notes are the building blocks for diminished and augmented chords, and they enable us to alter the quality of diatonic chords and create a richer harmonic landscape.

Another effective technique for adding harmonic interest is inter-module changes. By strategically modulating the relative key, we can introduce new harmonic colors and create unexpected twists in our compositions.

Relative Minor: E Minor

Every key signature has a corresponding key of the opposite quality that contains the same notes. Modulating to the relative key allows you to maintain the same tonality as the original set of chords provide while shifting the tonal center.

- The relative minor:

The relative minor is found on the sixth scale degree, the submediant. In G Major, that’s E minor.

- The relative major:

In a minor scale, the relative major is found on the third scale degree, the mediant. In E minor, that’s G Major.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

By modulating to E minor you get an entirely new tonal center with seven new diatonic chord functions. Your previous G major tonic now holds a mediant chord function instead. For more information about E minor, check out the article"Learn the Chords in E Minor".

You can open up a world of interesting chord progressions and intervals by exploring the relationship between the two relative keys. You can add subtle depth by alternating between E minor and G major. For instance, play in E minor for introspective sections and modulate to G major for an uplifting and energetic quality.

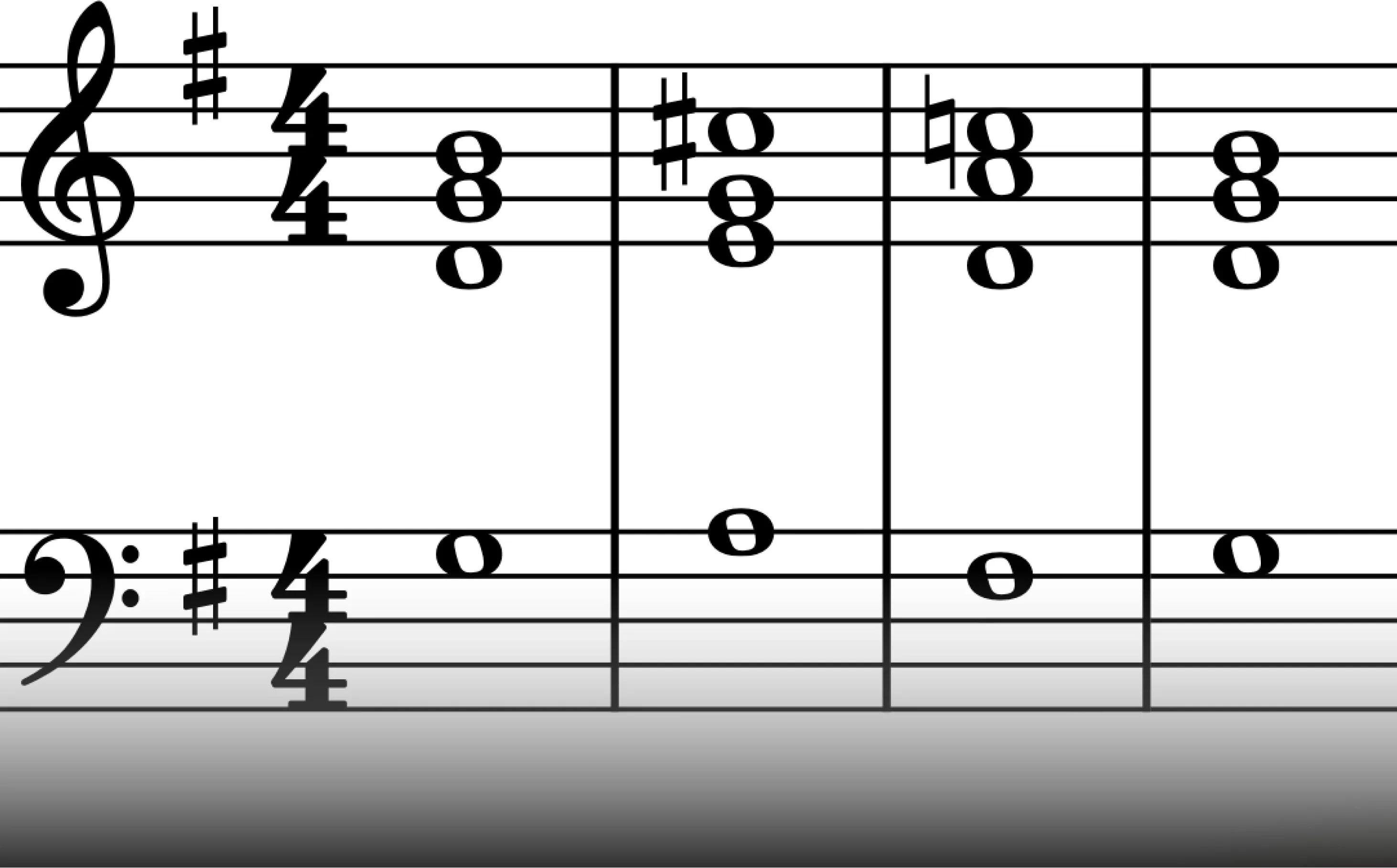

Adding Complexity to G Major Chord Progressions

To add harmonic interest to your music without modulating to a different key or using the relative key, you can employ parallel chords and secondary dominants. These two techniques can rapidly add depth and unexpected harmonic development to your music without disrupting the overall tonality of the song.

Parallel Chords

By applying accidentals, you can alter the quality of any diatonic chord, creating unexpected harmonic twists. For example, raising the 7th scale degree from C to C# can transform a diminished VII chord into an F# minor chord.

Additionally, simply shifting the tonic from major to minor can infuse your music with a dark and intriguing harmonic quality. For more examples of creating dark-sounding music, explore the article "Dark Chord Progressions" to discover techniques for making your music more sinister and haunting.

Remember, it's best to use parallel chords sparingly. Overusing them can cause your music to lack a harmonic focus which is important to keep the listener engaged. Use them intentionally to highlight specific sections and create surprising harmonic moments.

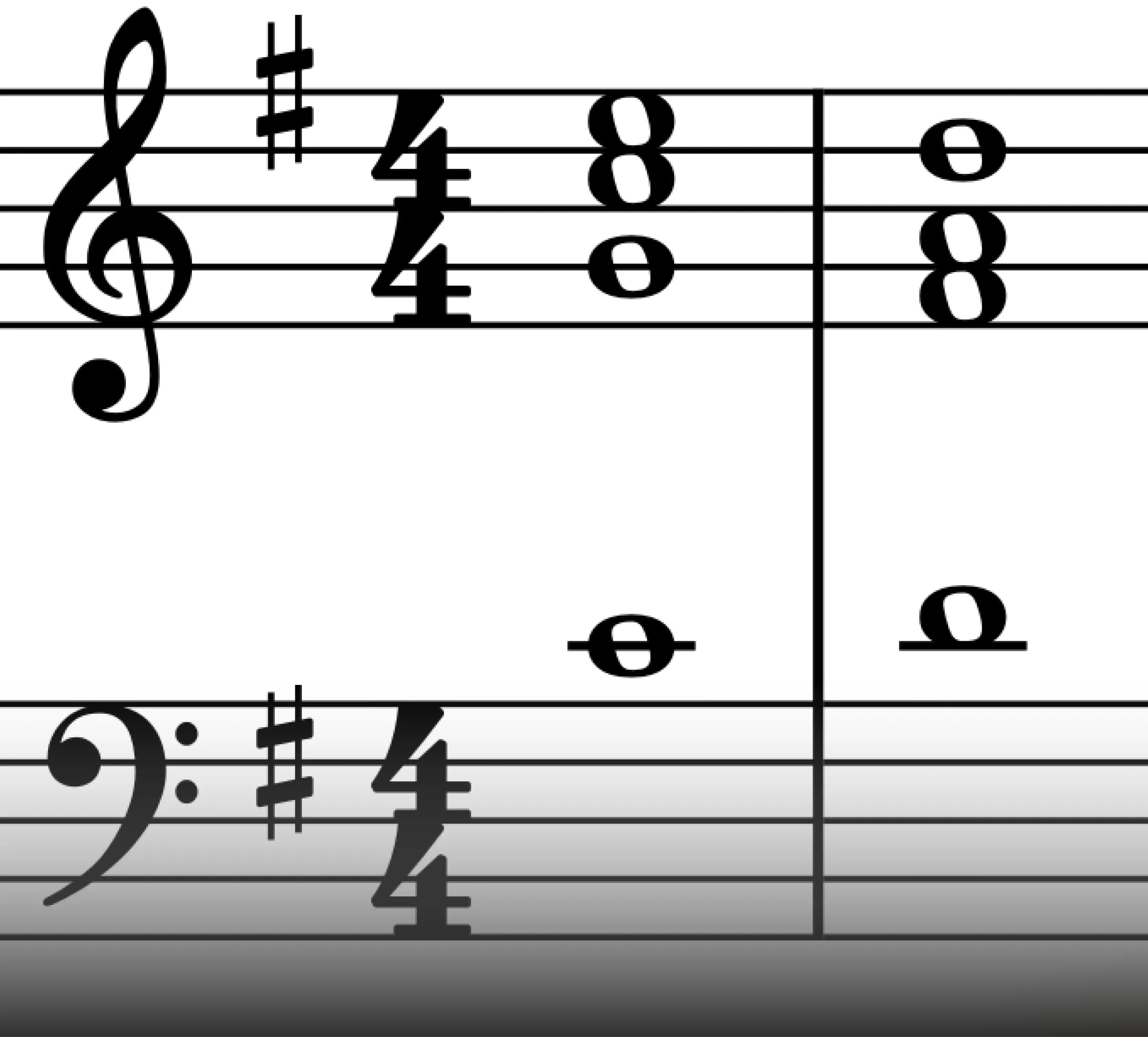

Secondary Dominants

A secondary dominant is a dominant chord function borrowed from a different key signature. This technique allows you to employ the powerful V-I interval from other keys to make your music more complex and harmonically interesting.

One of the most common types of secondary dominants is called the"dominant of the dominant"(V/V). This involves temporarily treating your dominant chord as a tonic and preceding it with its own dominant chord - the secondary dominant.

In the key of G Major, the dominant chord is D Major, and the secondary dominant is A Major (the dominant of D).

Here’s an example of this:

I (G) - V/V (A7) - V (G7) - I (G)

Even a foundational understanding of music theory can significantly elevate your music production and songwriting abilities. Explore our blog for valuable music theory resources to help you take your music to the next level.

How Musiversal Can Help You Write the Best Music

A solid understanding of music theory is invaluable when collaborating with Musiversal's talented musicians. This knowledge empowers you to effectively communicate your musical vision and ensure your ideas are accurately translated.

For example, including a V/ii in your chord chart signals the intent of a secondary dominant, guiding musicians' voice-leading decisions to connect chords.

If you need assistance writing compelling chord progressions or adding harmonic depth, our pre-production and songwriting experts are here to help.

With a Musiversal Unlimited membership, you gain unlimited access to a network of over 100+ professional musicians and expert engineers. Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights, behind-the-scenes action, and in-depth content, marketing advice, and much more. Sign up today and elevate your musical journey!

Join The Musiverse: Your free space to connect, create, and compete.

Collaborate with global creators, level up in live workshops, and win exclusive prizes. Join the community today!

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist