Learn the Chords in Ab Major: A Music Theory Resource

Master the Ab Major Key: Discover essential chords, useful progressions and techniques to elevate your music production and composing skills.

Introduction

Even a foundational understanding of music theory can instantly improve the way you approach songwriting as a producer or composer. By mastering the core concepts like harmony, diatonic and chromatic chords, scales, and intervals, you can write compelling and interesting chord progressions with a new sense of confidence.

In this guide, we’ll take an in-depth journey through the Ab major key signature, exploring its unique harmonic landscape and practical applications in your music. Here’s what you’ll learn:

- Understanding the 7 Diatonic Chords of Ab Major and Their Functions Learn the foundational chords of Ab major to create emotionally impactful progressions with tension and resolution.

- How to Write Memorable Progressions in Ab major We’ll analyze real-world examples to understand chord choices that evoke emotions and drive songs forward. This will show you how you can approach writing harmonically interesting progressions with intention.

- Expand Your Harmonic Horizons with Modal Interchange Use advanced techniques like modal interchange, secondary dominants, and parallel chords to add depth and variety to your music.

One of the purposes of learning music theory is to eliminate the need for guesswork about what sounds good. This will allow you to write music faster and more efficiently.

The Basics of Ab Major

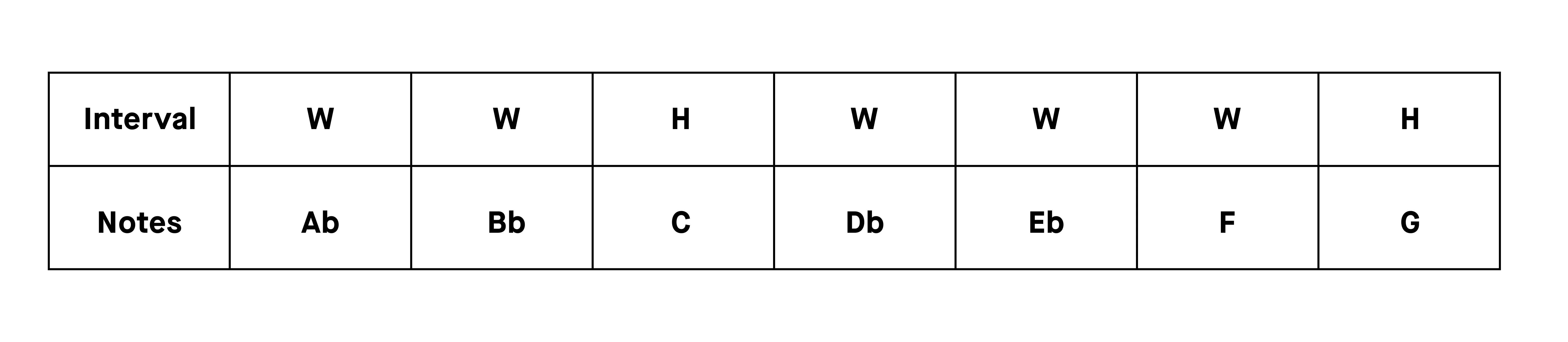

The Ab major scale, often referred to as the Ionian mode in music theory, follows a specific pattern of notes starting on Ab. Here's the sequence:

Each note in a scale holds a specific position, known as its scale degree, which determines its harmonic function and role within the key. These scale degrees are crucial for understanding the relationship of each note to the tonic and the overall structure of the key.

- Ab - Tonic: The home note, providing stability and resolution.

- Bb - Supertonic: A step away from the tonic, often leading to the mediant or dominant.

- C - Mediant: Bridges the tonic and dominant, adding color to harmonies.

- Db - Subdominant: Prepares for movement to the dominant, offering a sense of tension.

- Eb - Dominant: Second in importance to the tonic, driving resolution back to it.

- F - Submediant: Adds contrast, often used in progressions with the tonic or dominant.

- G - Leading Tone: Creates strong tension, resolving naturally to the tonic.

These seven degrees form the foundation of diatonic chords in the Ab major key, each contributing a unique harmonic function and color. A chord's function can be understood as its sense of stability or instability relative to the tonic, shaping the emotional and structural flow of your music.

Later in the article, we’ll delve deeper into chord functions, exploring their roles and common uses.

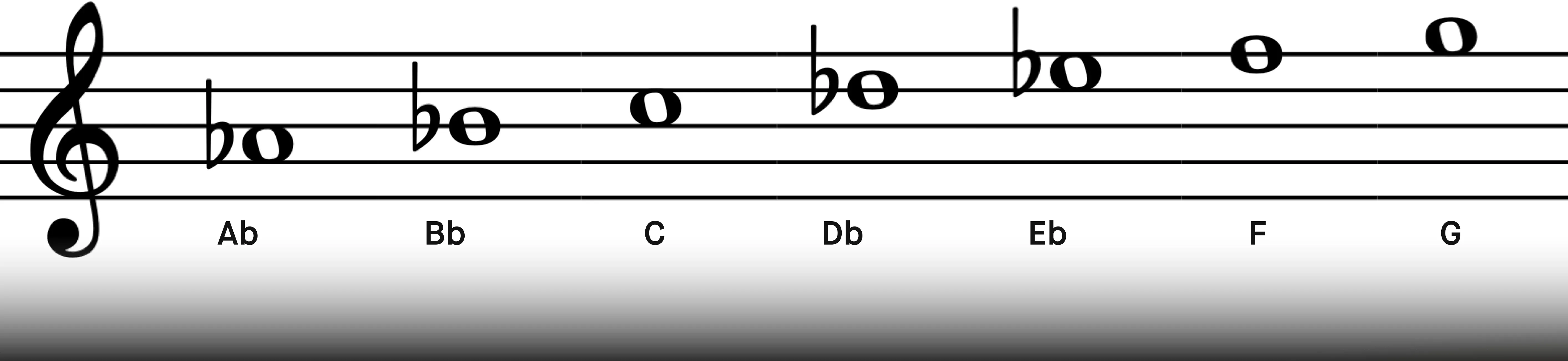

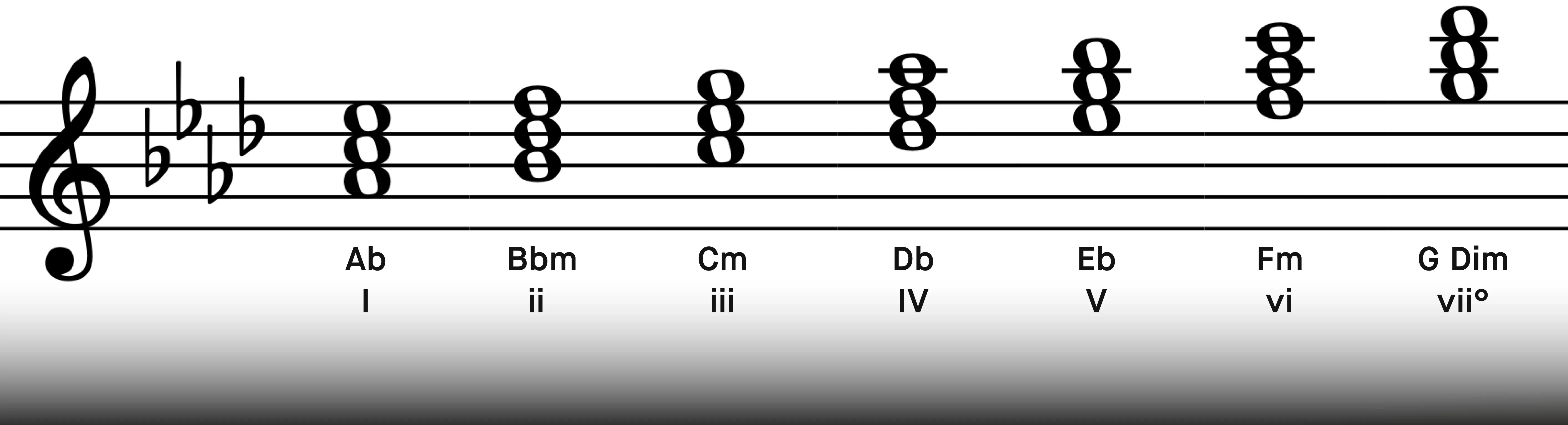

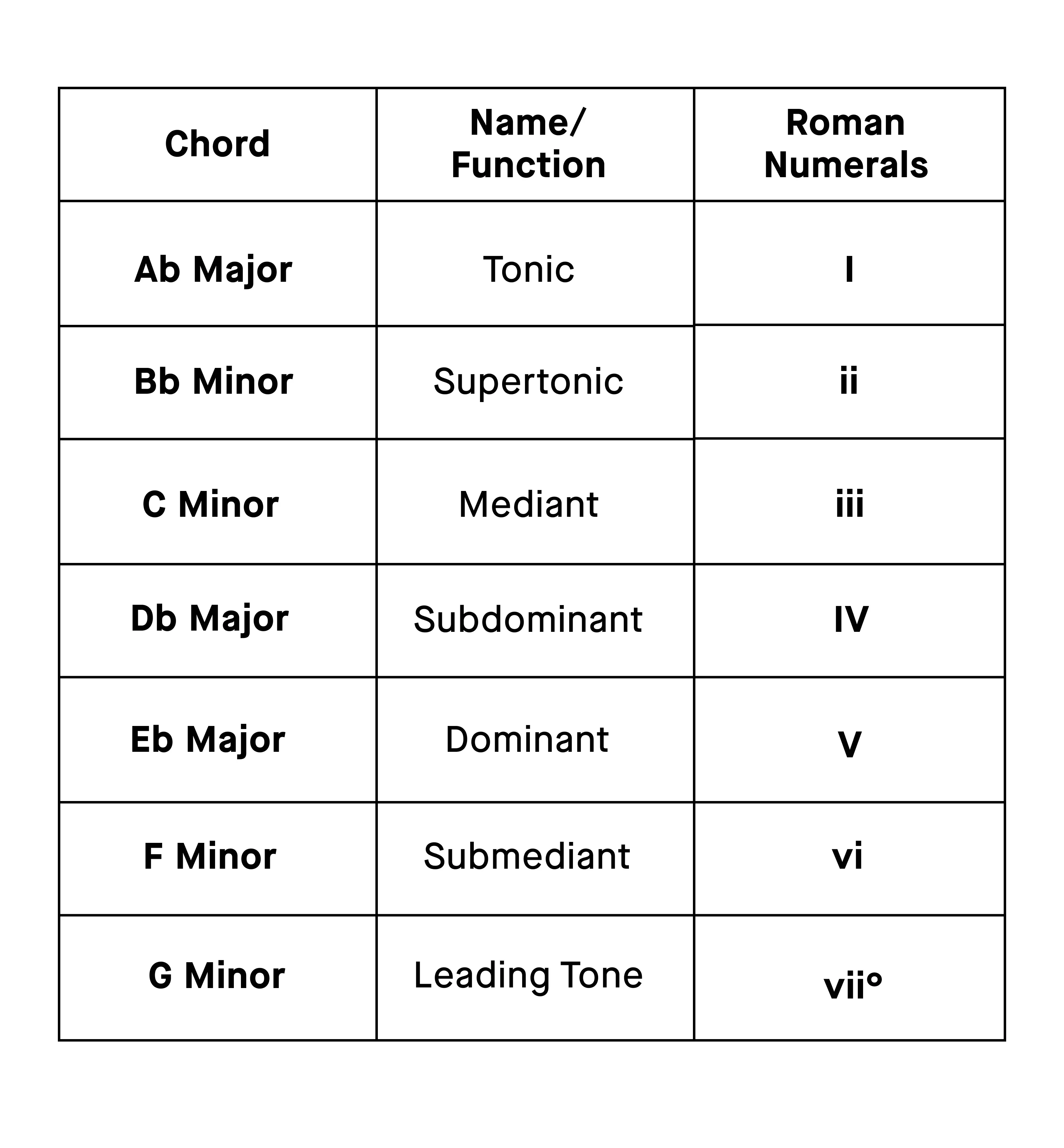

Chords and Roman Numerals

Roman numerals are used to indicate both the function and quality (major or minor) of chords within a key. Uppercase numerals represent major chords, while lowercase numerals mean minor chords.

The numeral itself corresponds to the chord's scale degree and harmonic function. For example, the I represents the tonic chord - Ab, in this case. Uppercase V means a major dominant chord, which in the key of Ab is Eb.

Roman numerals offer a key-independent way to describe harmonic structure and function. No matter the key signature, a V chord always serves as a dominant function, generating tension that tends to resolve to the tonic.

This system enables you to communicate harmonic ideas without being tied to specific chords. For instance, the I-V interval keeps its essential quality and function in any key signature, whether it’s Ab major, C major, D# minor, or another key.

Understanding Diatonic and Chromatic Notes in Ab Major

The notes naturally occur when you follow the Ionian pattern starting on Ab are the foundation of the key signature and are known as diatonic notes. The remaining notes are called chromatic notes. They can be used to add richness, depth, and unpredictability to your music.

When used intentionally, chromatic notes can enhance your melodies and chord progressions by introducing tension, color, suspens, intrigue and make your music less predictable. However, it’s important to approach chromatic notes and chords with care to avoid a sudden harmonic shift from sounding to unintentional or jarring (unless that’s on purpose). Learning how to incorporate all 12 notes regardless of the key you’re in can unlock a whole world of new harmonic possibilities and opportunities. Chromatic notes are especially useful for:

- Creating tension to resolve back to diatonic tones.

- Modulating to new keys.

- Altering the quality of diatonic chords takes your music in an unexpected direction

When a diatonic note is modified, it’s referred to as an accidental. These alterations are notated using sharp (♯) or flat (♭) symbols, while the natural (♮) symbol is used to restore the note to its original diatonic pitch.

Chords in Ab Major

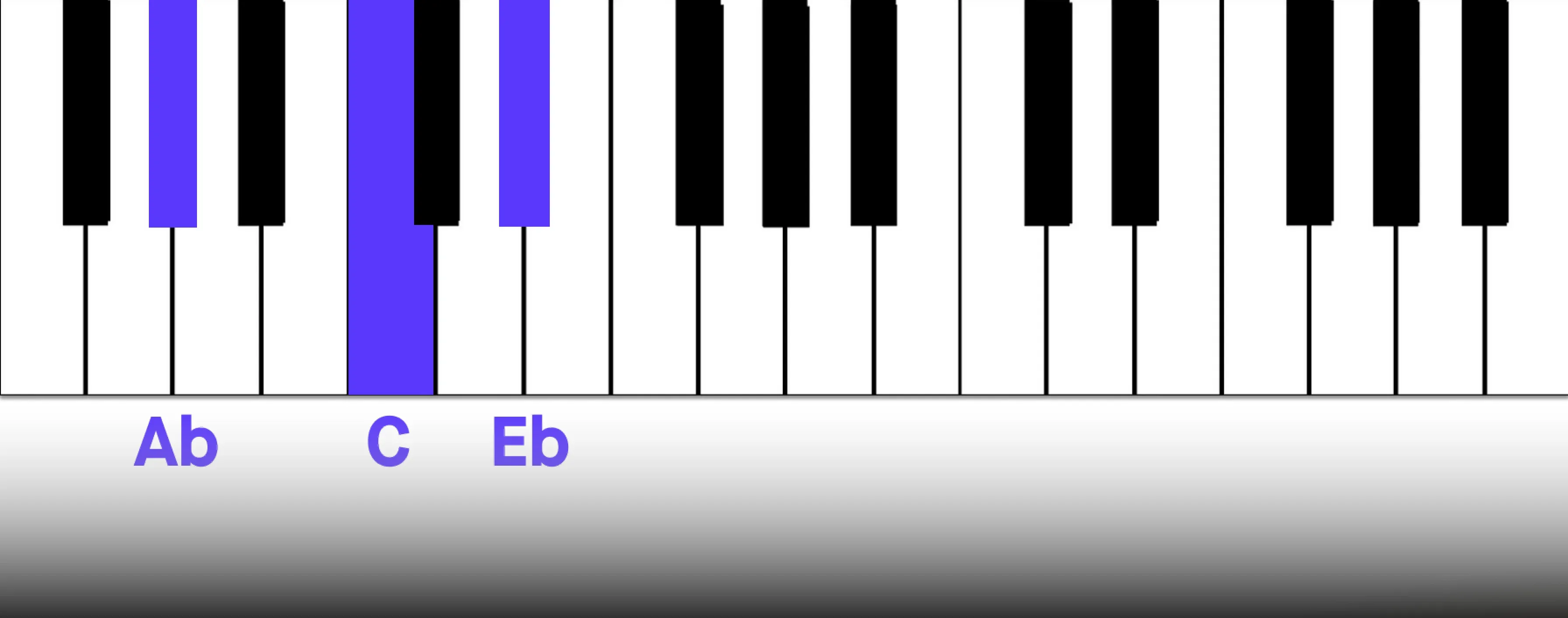

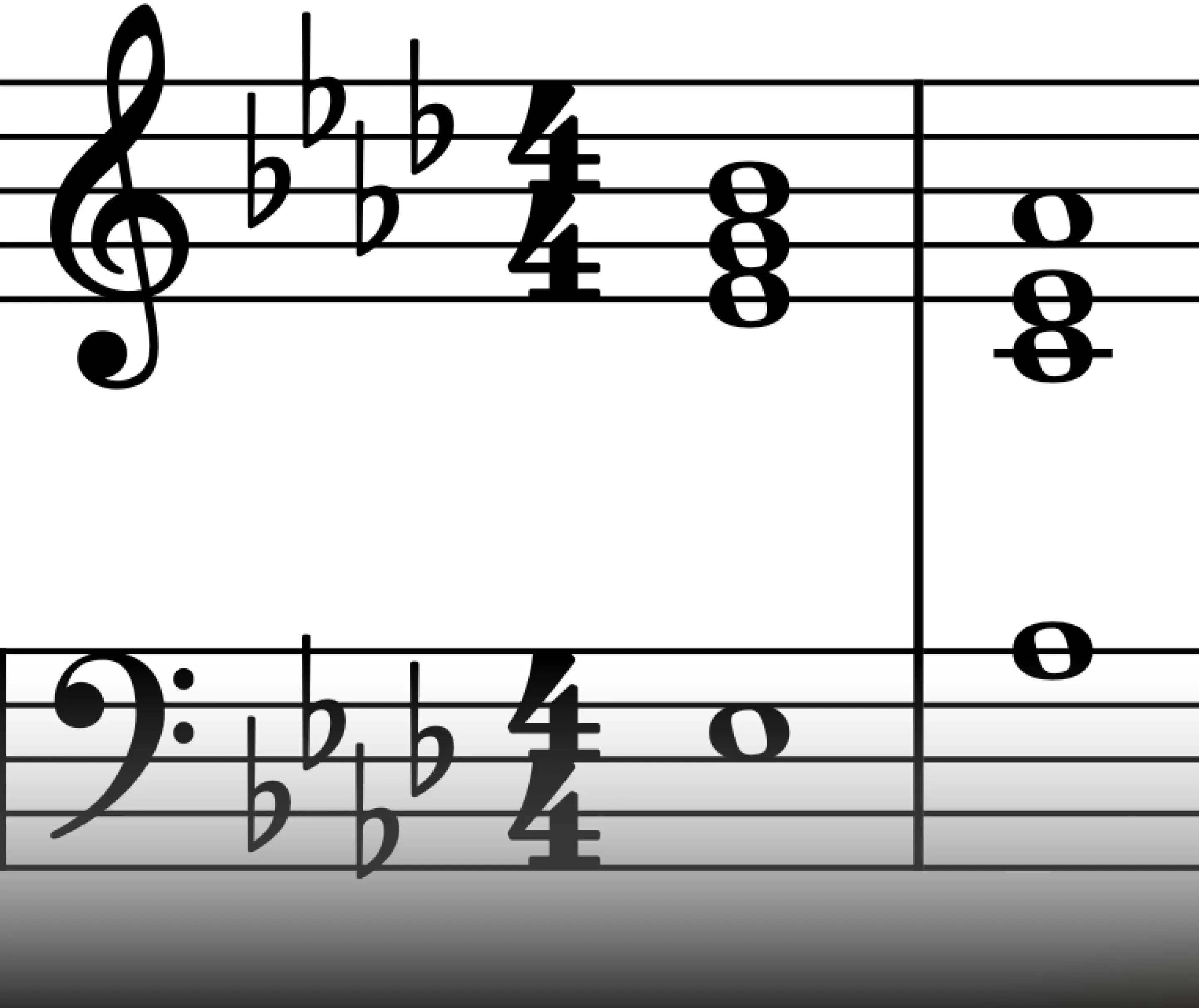

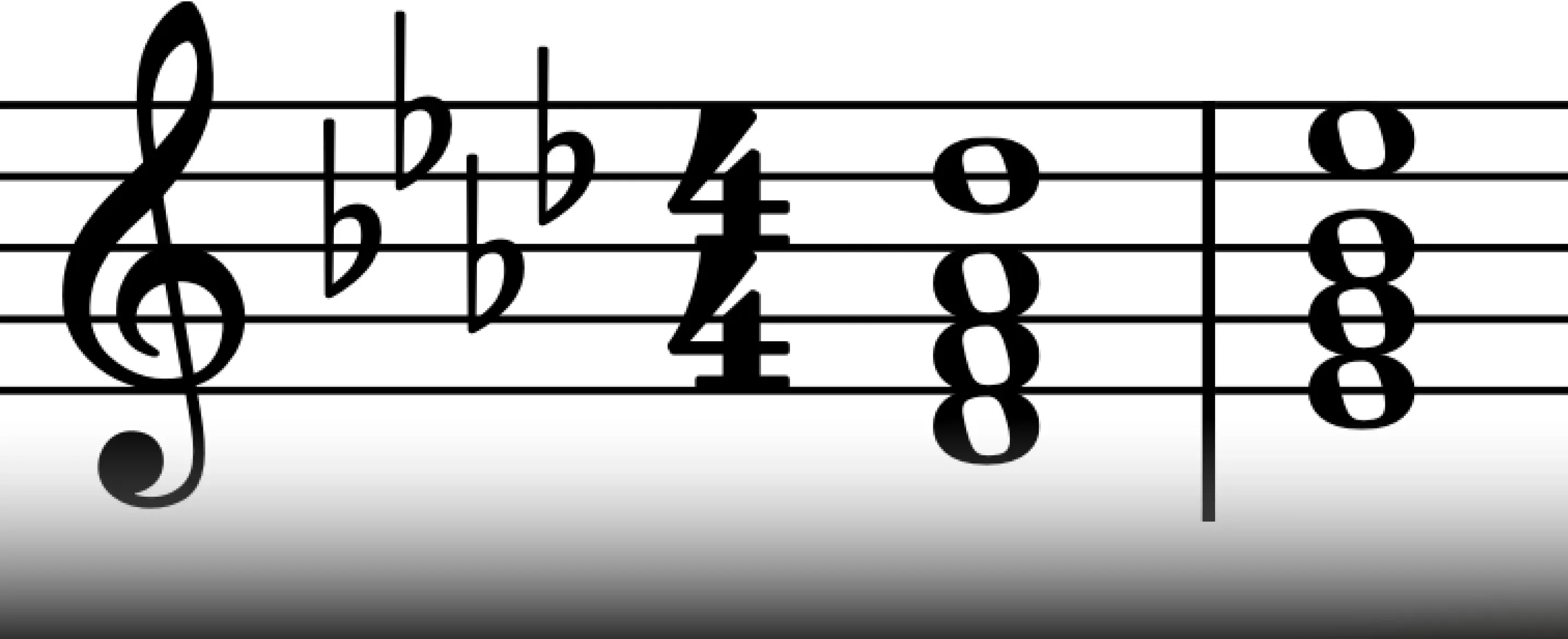

I: Ab Major

The tonic chord, Ab major, serves as the foundation of the scale, providing a sense of stability, resolution, and rest. Unlike other chords in the key, the tonic doesn’t inherently"need"to move elsewhere, reinforcing its role as the most stable and grounded chord in the key.

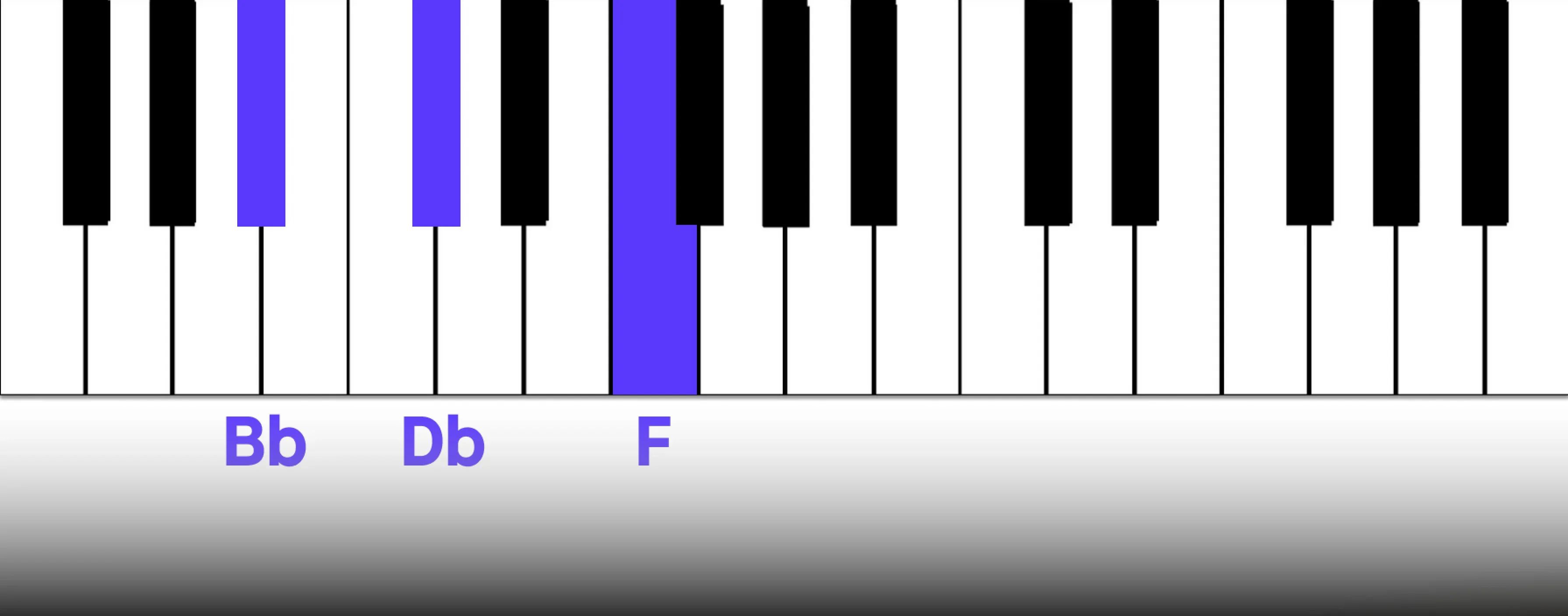

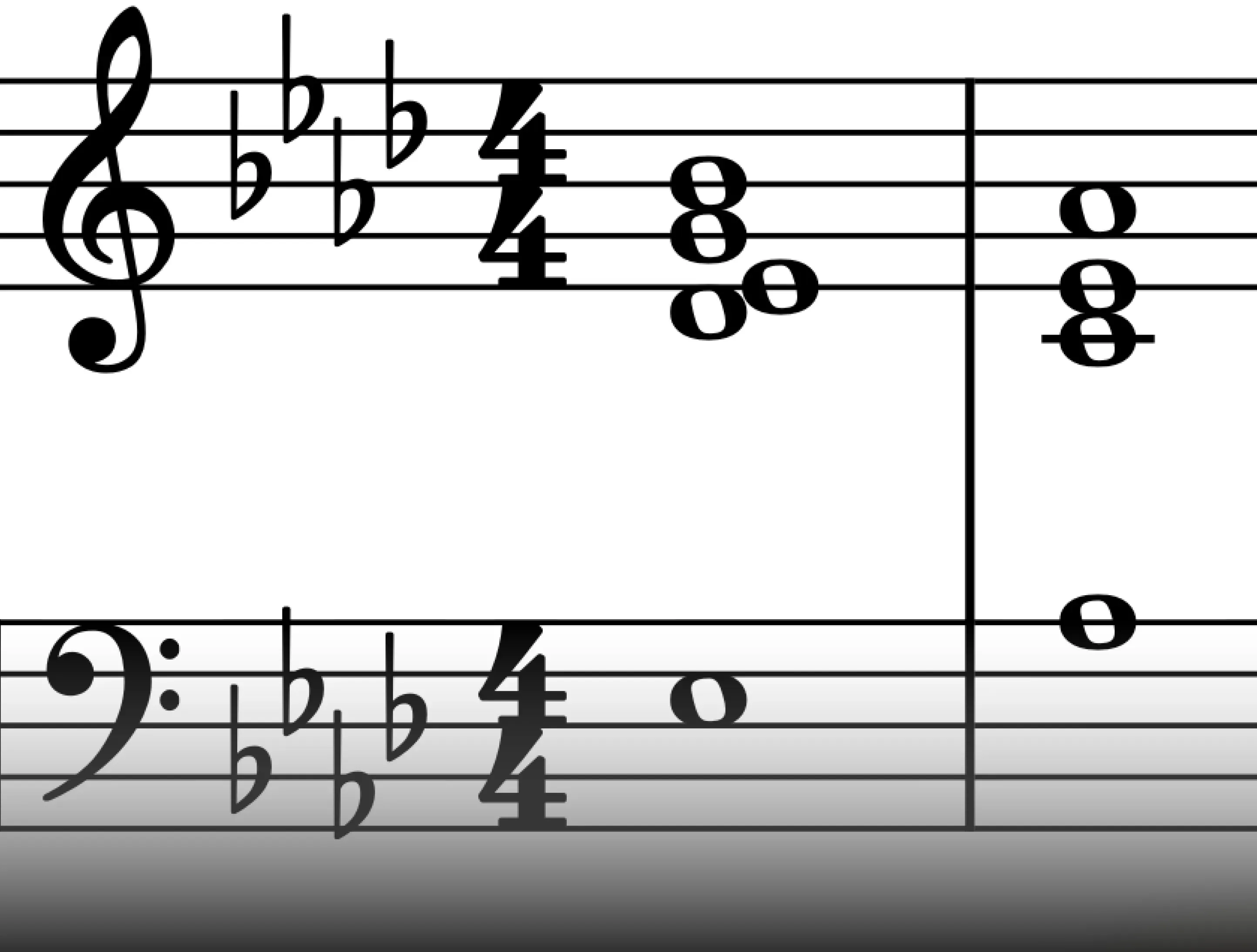

ii: Bb Minor

The supertonic chord, Bb minor, is a versatile chord. When moving away from the tonic, it often resolves to the dominant, giving it a subdominant function. This creates a sense of tension that propels the progression forward. On the other hand, when moving toward the tonic, Bb minor can provide a smooth voice leading for a smooth resolution to the home of the key. The sound quality of the chord is somewhat more somber than the other commonly used minor vi chord.

In jazz, the ii chord plays an important role in the popular ii-V-I progression, where it sets up movement toward the dominant which then resolves back to the tonic.

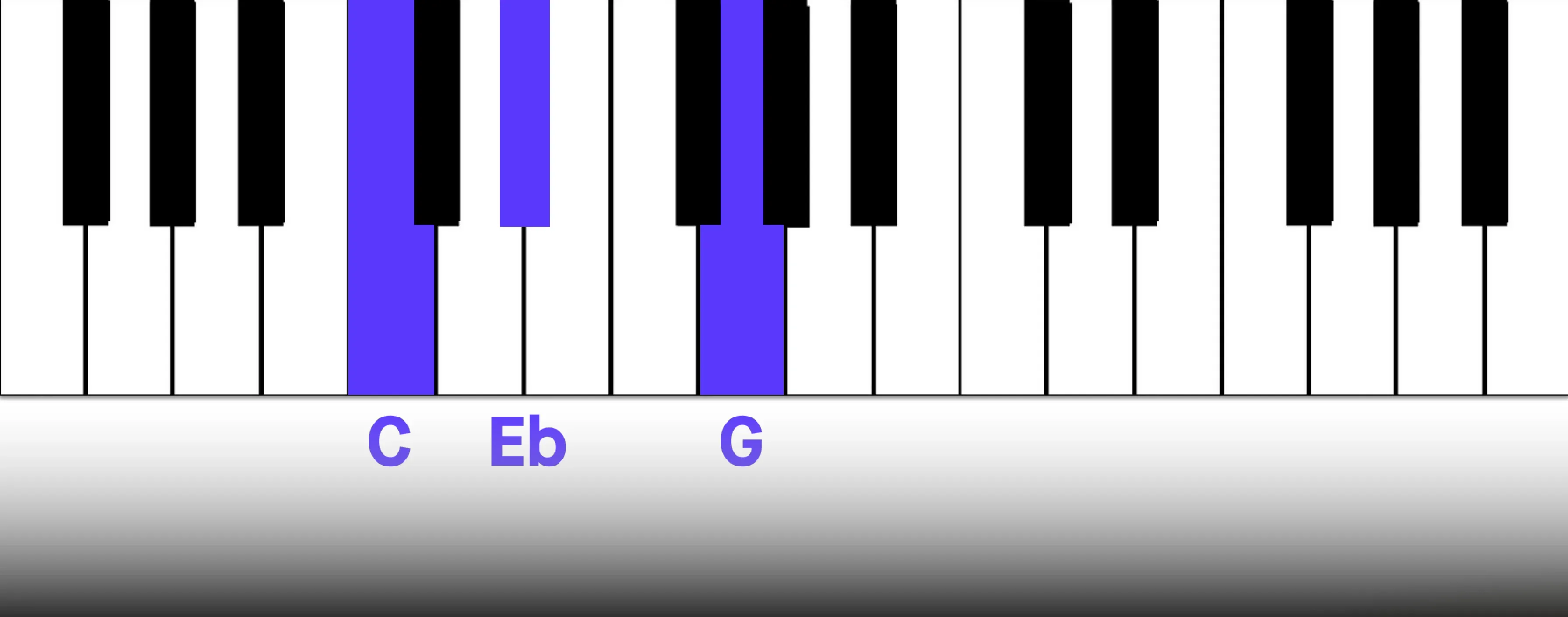

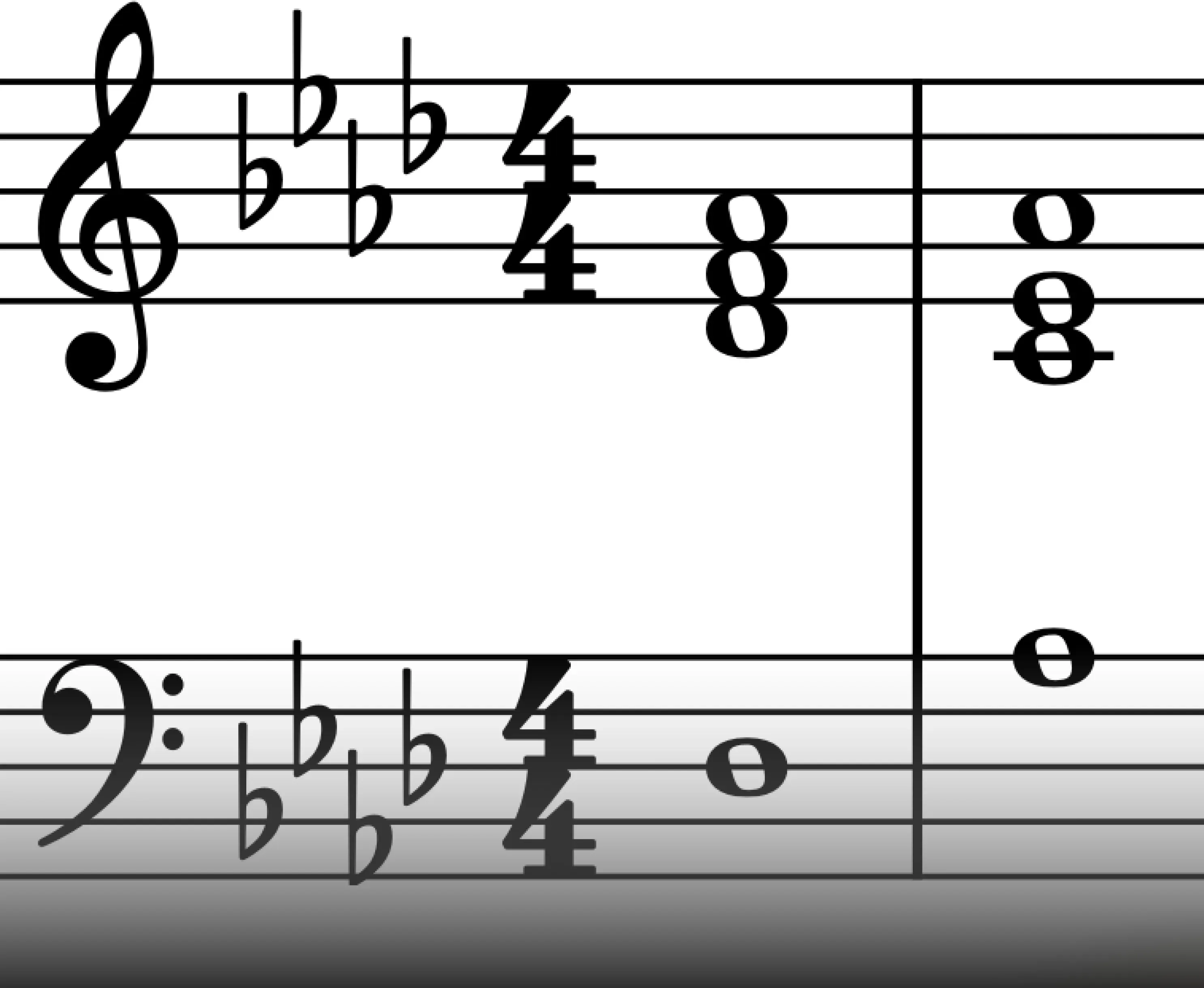

iii: C Minor

The mediant chord, C minor, shares two notes with the tonic, creating a tonal similarity despite their differing qualities. For that reason, the mediant can function as a tonic substitute, which can provide a sense of rest - similar to the tonic - but with a different harmonic color. Using tonic substitutions adds variation and a sense of dynamic movement in your music. By not consistently resolving to the tonic, you can heighten its impact when you eventually do return to the tonic chord.

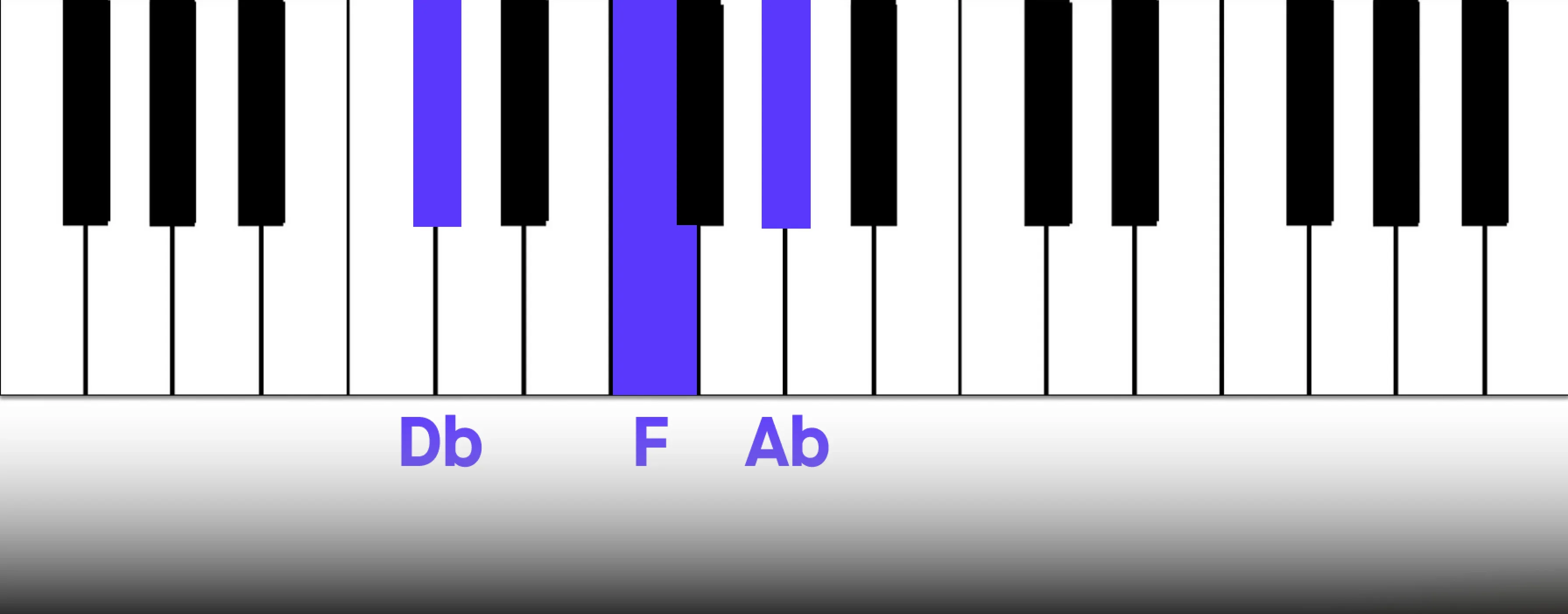

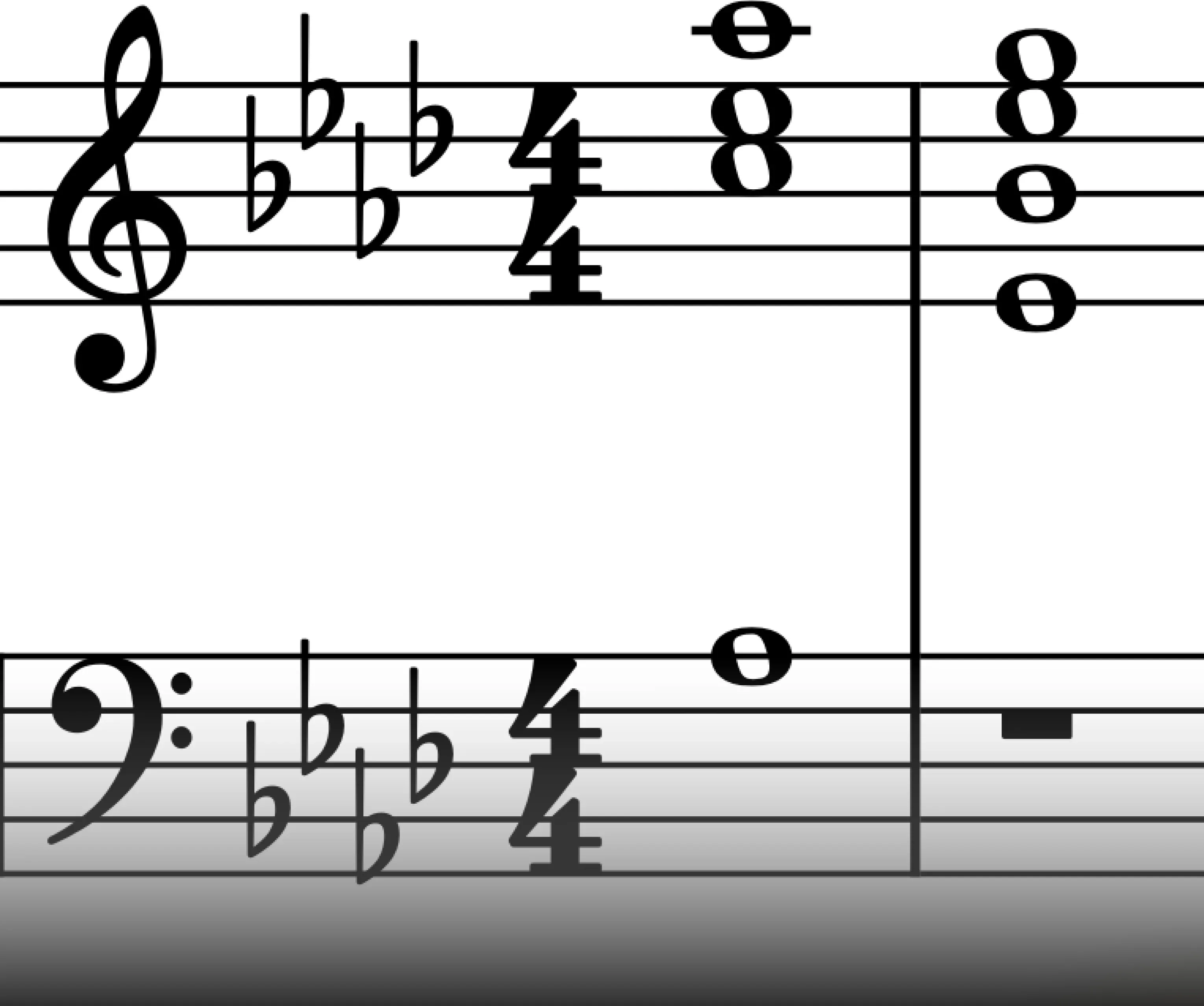

IV: Db Major

The subdominant chord plays an essential role in creating both harmonic contrast and anticipation. It provides a shift away from the tonic and sets up movement toward the dominant. When followed by the V chord, it further intensifies the tension. This tension sets the stage for a powerful resolution back to the tonic.

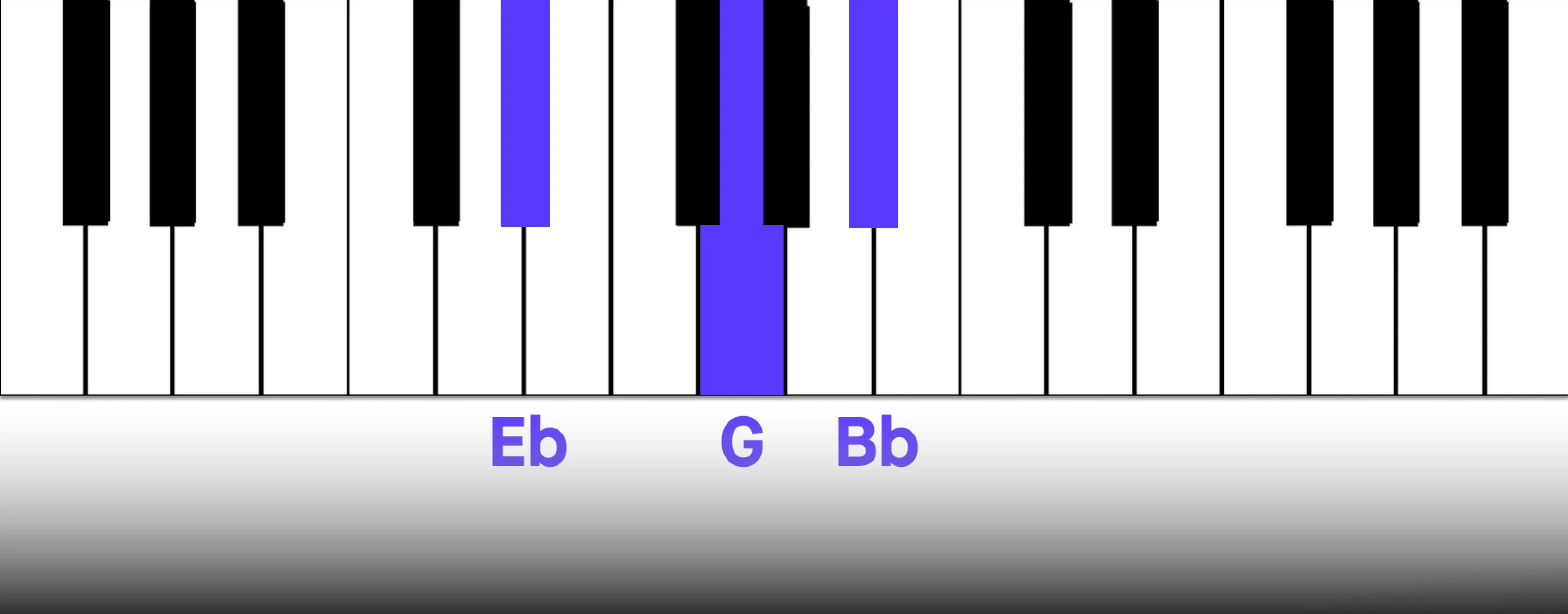

V: Eb Major

Along the tonic, the dominant chord is the most important chord in any key. The tension it offers has a strong pull to resolve to the tonic. The reason is because the third degree of the dominant chord is only a half step away from the root of the tonic. This creates a sense of urgency and need for resolution.

The relationship between the dominant and tonic is one of the cornerstones in traditional western music theory.

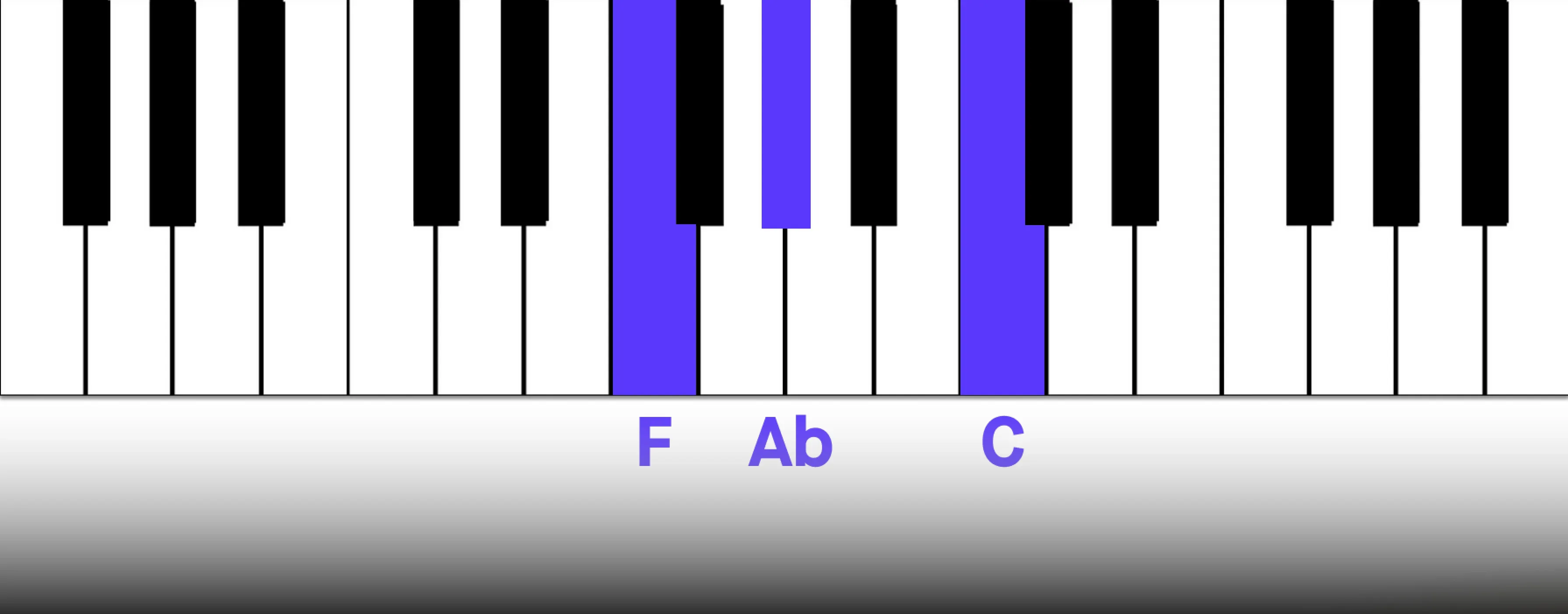

vi: F Minor

The submediant chord is important for a couple of different reasons. It can be used as a tonic substitute that offers a sense of stability but in a contrasting color to the tonic. Furthermore, the sixth scale degree is also the tonic of the relative minor key. Therefore the submediant chord can function as a bridge between two different tonal centers. We'll explore this concept of modal interchange in more depth later.

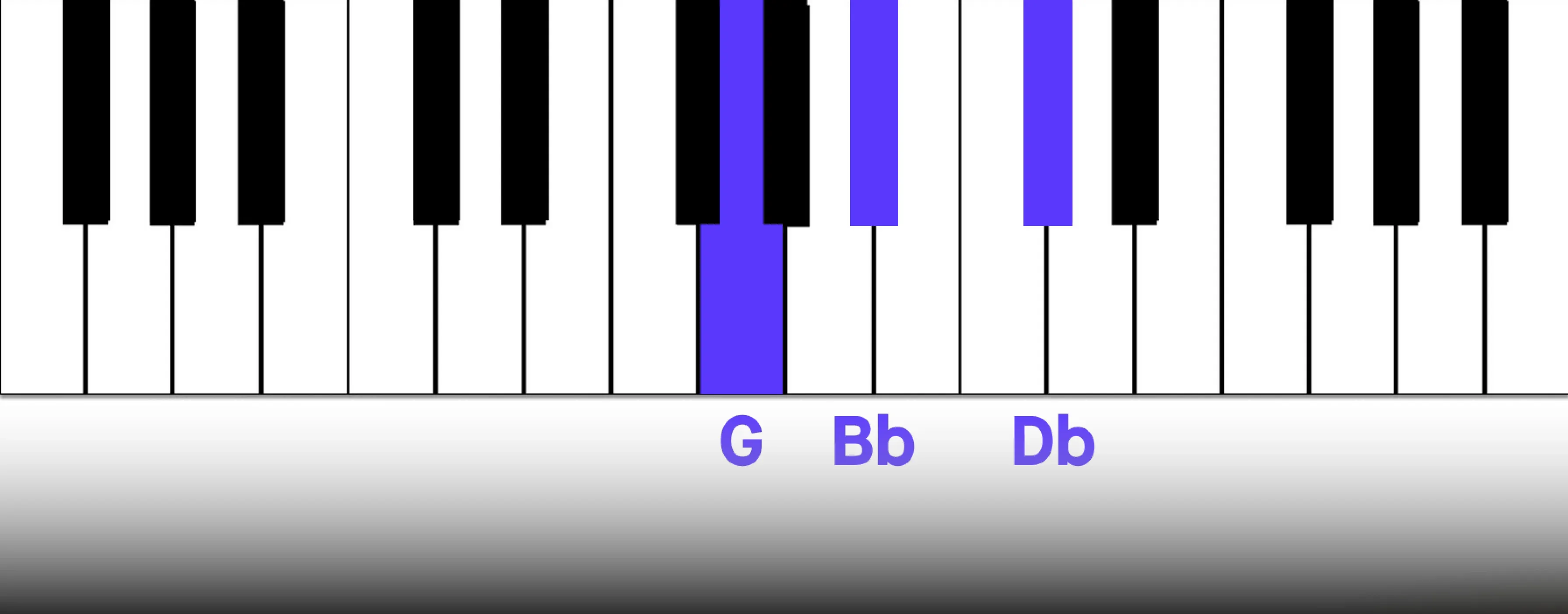

vii°: G Diminished

Diminished chords are characterized by an interval of a tritone (the devil’s interval), which creates a sense of instability and tension. In a major key, the diminished chord often functions as a leading-tone chord, meaning it pulls toward the tonic. The inherent dissonance of this chord seeks to resolve to a place with more harmonic stability.

In pop and rock music, the diminished chord is often used as a passing chord or to create a dramatic moment just before resolving powerfully to the tonic. Its dissonance heightens anticipation, making the resolution more impactful. Holding the diminished chord for an extra beat or two can further amplify this tension.

Primary and Secondary Chords in Ab Major

Primary Chords

The primary chords are I, IV, and V and they form the harmonic backbone of the key. These chords are essential for establishing the tonality and stability of the progression.

Secondary Chords

The secondary chords, ii, iii, vi, and vii°, add color, complexity, and movement to your progressions as they provide specific harmonic flavors that can enrich the overall musical landscape. They offer a greater harmonic variety for more engaging chord progressions.

Understanding Chord Relationships and Intervals

Experimenting with different chord intervals and combinations is a great way to understand the harmonic and tonal relationships between diatonic chords. Make sure to also break free from triads in root position and to explore chord inversions. The order of the notes changes the sound and the chord’s sense of stability.

For example, a tonic chord with the fifth or third in the bass can act as a subtle tonic substitute, offering a less defined, sense of resolution in a progression.

By practicing various chord intervals, you'll broaden your musical vocabulary, allowing you to quickly identify the right chord for your intentions. You’ll reduce the trial-and-error of testing different chord combinations until you find what you’re looking for. In both melodic and chordal writing, it’s important to be able to recognize intervals between notes. The most effective way to recognize intervals is to connect them to familiar songs. In our article on Ear Training we provide examples of both ascending and descending intervals. Knowing which intervals you hear in your head will make your melodic writing easier and more efficient.

Cadences in Ab Major chord progressions

Cadences are the musical equivalent of punctuation marks in language. Just as periods, commas, question marks, and exclamation points allow us to convey meaning when we speak and write, cadences also provide a sense of resolution, closure, anticipation, or ambiguity.

By using specific cadences strategically throughout your song, you can amplify the emotional impact while creating natural dynamic movements. In the following section, we'll explore the most common cadences and how they can be used to enhance your music’s emotional impact.

Perfect Cadence

Dominant → Tonic (V - I)

Eb → Ab

The perfect cadence moves from the dominant to the tonic chord, and it is the most definitive and powerful cadence. It provides a strong sense of closure and finality.

To further intensify the emotional impact of this resolution, you can incorporate a dominant seventh chord before the tonic. The added seventh creates additional tension in the dominant chord, making the eventual resolution to the tonic even more powerful and satisfying.

Eb7 → Ab (V7 - I)

In a perfect cadence, both chords must be in root position to create a strong and stable resolution. Additionally, the top voice of the final chord needs to be the root note of the tonic.

Plagal Cadence

Subdominant → Tonic (IV - I)

Db → Ab

The plagal cadence, often called the"Amen Cadence,"provides a softer, more subdued conclusion than the perfect cadence. This cadence is commonly heard at the end of traditional hymns with the word"Amen", which is where it gets its nickname.

Half Cadence

Tonic, or Supertonic, or Subdominant → Dominant: (I / ii / IV → V)

Ab→ Eb

Bbm → Eb

Db → Eb

A half cadence ends a musical phrase on the dominant chord, creating a sense of suspension rather than resolution. Unlike the definitive closure provided by perfect and plagal cadences, the dominant chord's inherent instability leaves the progression feeling unresolved.

For instance, ending a bridge or pre-chorus on the dominant chord builds anticipation, setting up a powerful resolution when the tonic begins the next section. This technique can dramatically heighten the dynamic flow of your song, adding tension and excitement as the music moves forward.

Interrupted Cadence

Dominant to Submediant (V - vi)

Eb → Fm

An interrupted cadence suggests a strong and definitive resolution, only to unexpectedly end on the submediant chord. The interrupted cadence can serve as a smooth pivot for modulating to the parallel key.

Common Chord Progressions in Ab Major

In this section, we'll look at chord progressions in Ab major from well-known songs. We’ll explore chord progressions varying in complexity while keeping an eye on chord chord functions and cadences. Now, let's dive into some common and captivating Ab major chord progressions.

I (Ab) - IV (Db) - ii (Bbm) - V (Eb)

This chord progression uses the minor ii chord with a subdominant function, adding a different emotional color compared to the major IV subdominant function. This exact progression is used in the chorus to Celine Dion’s “The Power of Love”. The interplay between upward and downward motion in the chord progressions adds a natural ebb and flow sensation, which creates a natural movement. A minor ii chord in a major scale carries a uniquely somber and introspective quality, setting it apart from the other diatonic minor chords. Unlike the iii and vi chords, which are more closely related to the tonic and feel harmonically stable, the minor ii introduces a subtle tension and emotional depth.

The slightly unresolved character of the chord makes it an ideal choice for songs that explore themes of longing and passion. The subdominant feature of a minor ii chord evokes a vulnerability that the other minor chords lack.

I (Ab) - vi (Fm) - ii (Bbm) - Vsus2 (Ebsus2) - V (Eb)

This chord progression delivers a mix of drama and hope, making it a perfect fit for John Legend’s “All of Me”. While it begins and ends with major chords, the middle section introduces two minor chords and a suspended chord, adding emotional complexity.

The suspended chord is especially effective as a bridge between the major and minor tonalities, as it is harmonically neutral - neither major nor minor. This neutrality allows for a seamless transition.

Despite being in a major key, the song doesn’t quite “feel” major. This showcases how music can convey a wide range of moods and emotions regardless of the quality of the key.

I (Ab) - V (Eb) - ii7 (Bbm7) - IV (Db)

Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” features a straightforward and simple chord progression in the chorus, but its emotional impact lies in the modulation between relative keys. The song begins in F minor and transitions to Ab major in the chorus, creating a shift in tone.

This modulation adds a sense of energy and dynamism without the need for changes in instrumentation, tempo, or other production techniques. The move from a minor to a major key provides a natural uplift, which works great with the emotional arc of the song. Modulating between relative keys is an excellent way to add variety and maintain listener interest while maintaining the overall tonal cohesion of the song. This technique keeps the song engaging and dynamic, avoiding the risk of it becoming stagnant or overly repetitive. We’ll return to relative keys further down.

I (Ab) - vi (Fm) - IV (Db) - V (Eb)

Sting and The Police are known for their use of complex chords and unusual time signatures. Their song “Every Breath You Take” offers excellent examples of how you can add complexity to your chord progression to keep the listener engaged. The intro and verse feature a seemingly simple chord progression, primarily sticking to the primary chords with one secondary chord added for subtle minor color and variation.

What makes this progression more harmonically engaging, however, is the inclusion of chord extensions. In this case, each chord contains a 9th (the supertonic an octave higher). This note is in the melodic plucking pattern by the guitar, adding a sense of depth and sophistication, making the otherwise simple chord progression more interesting. Next, we’ll examine the chorus, where the harmonic and emotional intensity shifts further.

IV (Db) - iv (Fm) - I (Ab) V7/V (Bb7) - IV (Db)

The chorus of “Every Breath You Take” features a few harmonic elements that are particularly notable. First, it opens on the IV chord, immediately creating a sense of urgency and a drive for resolution. This immediately distinguishes the chorus from the verse.

Second, after returning to the tonic chord, the tension heightens again with the introduction of a secondary dominant chord (V7/V). In this case, the Bb major 7 chord functions as the dominant of Eb. This non-diatonic chord adds an unexpected harmonic twist keeping the listener engaged. Interestingly, the Bb major 7 chord does not resolve as expected to the V chord (which temporarily functions as a tonic). Instead, it leads back to the IV chord, another surprising and unconventional move that enhances the song’s unpredictability.

In the second repetition of the chorus, the harmonic approach shifts yet again. This time, the progression sticks to diatonic chords, creating a sense of stability and resolution. The chords are now I (Ab) - vi (Fm) - IV (Db) - V (Eb) - IV (Db).

This alternation between chromatic tension and diatonic simplicity is a great example of how contrast can be used to balance stability and instability and tension and resolution in a song, while maintaining harmonic coherence and interest.

Playing Chords Outside of the Key Signature

While the Ionian mode provides the foundational structure for the natural major scale, incorporating chromatic notes greatly expands the harmonic possibilities. These notes allow you to create more complex chord progressions to add depth and intrigue to your music.

Chromatic notes are essential for forming diminished and augmented chords, as well as altering the quality of diatonic chords. Another powerful technique for enhancing harmonic interest is modal interchange. By modulating to the relative key, you can introduce fresh harmonic colors and unexpected shifts in your music. The new tonal perspective can create emotional contrasts within your song.

For example, modulating to the relative minor (F minor in the case of Ab) allows you to keep the same set of notes while shifting the entire tonal center.

- The relative minor: The relative minor is found on the sixth scale degree, the submediant. In Ab major, that’s F minor.

- The relative major: In a minor scale, the relative major is found on the third scale degree, the mediant. In F minor, that’s Ab major.

Modulating Between Relative Keys

Modulating to F minor introduces a fresh tonal center, along with seven new diatonic chord functions. As a result, your original Ab major tonic now comes the mediant within the F minor key.

For a deeper dive into F minor, be sure to check out our article, "Learn the Chords in F Minor".

When you start exploring the relationship between these two relative keys, it’ll open up a wealth of creative possibilities. Alternating between F minor and Ab major adds subtle complexity to your music. For example, you could use F minor for more introspective, emotive sections and modulate to Ab major for moments of uplift and energy, creating a dynamic contrast throughout your composition.

Adding Complexity to Ab Major Chord Progressions

To introduce harmonic richness and complexity without changing keys or modulating to the relative key, you can use parallel chords and secondary dominants. These techniques allow you to temporarily expand the harmonic range and create unexpected twists and depth while maintaining the overall tonality of your song.

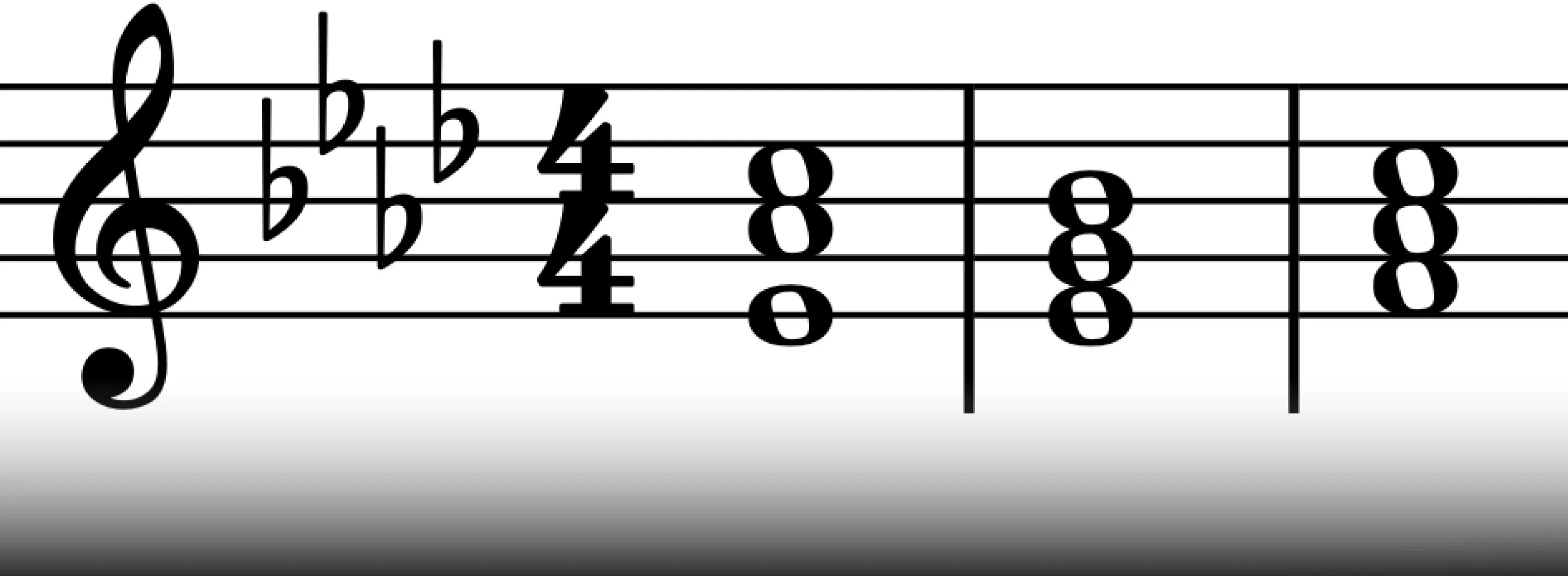

Parallel Chords

By applying accidentals, you can change the quality of any diatonic chord in order to add an element of surprise. For example, by raising the 3rd of your mediant chord, you go from Eb to E, which results in a C major chord.

Another effective technique is shifting the tonic from major to minor, which introduces a darker, more mysterious harmonic quality. If you're interested in exploring darker sounds, check out our article"Dark Chord Progressions"for tips on creating haunting, sinister music.

While parallel chords can be a powerful tool, it’s important not to overuse them. Doing so can lead to a lack of harmonic focus, making it harder for the listener to stay engaged. Instead, use parallel chords strategically to highlight key moments and add surprising twists to your progressions.

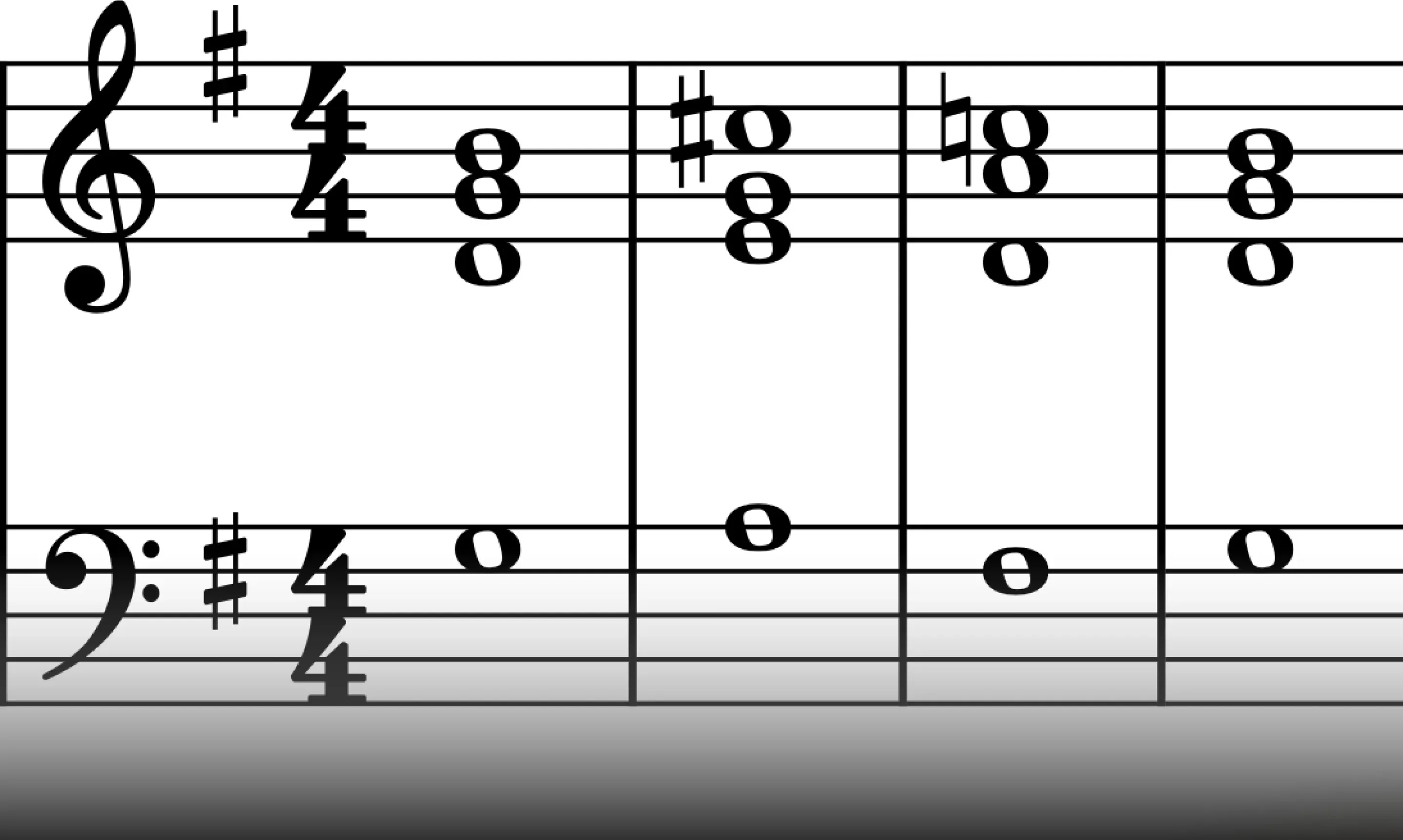

Secondary Dominants

A secondary dominant is a dominant chord borrowed from another key, temporarily introducing a dominant-to-tonic relationship from that key. You temporarily tonictize any of the diatonic chords by preceding it with that chord’s dominant. This technique allows you to incorporate the powerful V-I progression from different keys, enriching your music with harmonic complexity and interest.

One of the most common types of secondary dominants is the dominant of the dominant (V/V). This involves treating your dominant chord by preceding its own dominant chord - the secondary dominant.

For example, in the key of Ab major, the dominant chord is Eb major, and the secondary dominant would be Bb major (since this is the dominant of Eb).

Here’s how this could look in practice:

I (Ab) - V/V (Bb7) - V (Eb7) - I (Ab)

A solid understanding of music theory can greatly enhance your music production and songwriting skills. Make sure to keep visiting the blog for more valuable resources and insights on music theory and songwriting that will help you elevate your music and take your creativity to new heights.

How Musiversal Can Help You Write the Best Music

A solid understanding of music theory is invaluable when collaborating with Musiversal's talented musicians. This knowledge empowers you to effectively communicate your musical vision and ensure your ideas are accurately translated.

For example, including a V/ii in your chord chart signals the intent of a secondary dominant, guiding musicians' voice-leading decisions to connect chords.

If you need assistance writing compelling chord progressions or adding harmonic depth, our pre-production and songwriting experts are here to help.

With a Musiversal Unlimited subscription, you gain unlimited access to a network of over 80+ professional musicians and expert engineers. Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive insights, behind-the-scenes action, in-depth content, marketing advice, and much more. Sign up today and elevate your musical journey!

Your Music, No Limits.

Join the Waitlist